Howard Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2009 by Rob Lilwall

Originally published in Great Britain in 2009 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette Livre UK company

Published by arrangement with Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Howard Books

Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas,

New York, NY 10020

First Howard Books trade paperback edition April 2011

HOWARD and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event.

For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster

Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Interior design by Davina Mock-Maniscalco

Maps by Sarah Marshall

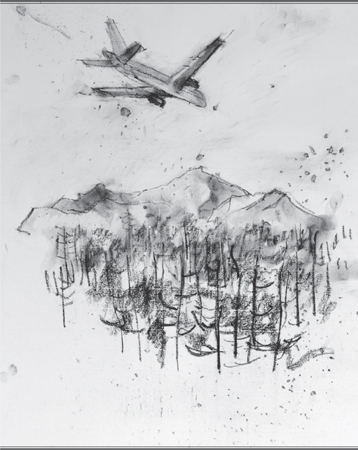

Illustrations by Tim Steward

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Liwall, Rob.

Cycling home from Siberia / Rob Lilwall.

p. cm.

1. Lilwall, RobTravelRussia (Federation)Siberia. 2. Bicycle touringRussia (Federation)Siberia. 3. CyclingRussia (Federation)Siberia. 4. Siberia

(Russia)Description and travel. I. Title.

GV1046.R82S535 2011

796.640957dc22

2010031402

ISBN 978-1-4516-0786-4

ISBN 978-1-4516-0787-1 (ebook)

For Christine

CONTENTS

This is my dilemma I am dust and ashes, frail and wayward, a set of predetermined behavioural responses riddled with fears, beset with needs the quintessence of dust and unto dust

I shall return but there is something else in me

dust I may be, but troubled dust, dust that dreams.

R ICHARD H OLLOWAY

Our moral nature is such that we cannot be idle and at ease.

L EO T OLSTOY

PART ONE

ENGLANDSIBERIA

September 2004

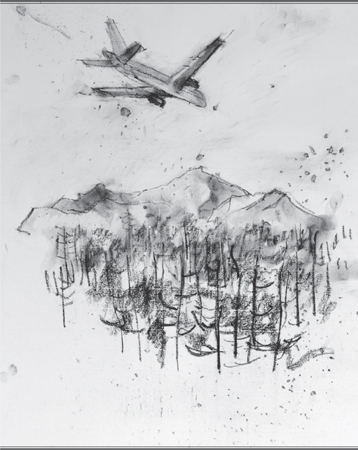

OVER MORDOR

Siberia impends through the darkness as the ultimate unearthly abroad.

The place from which you will not return.

C OLIN T HUBRON

W E HAD BEEN FLYING east all night, and I awoke to notice that it was already daylight outside the plane. Looking out the window onto the empty landscape below, the dark shades of brown and green reassured me that, although it was mid-September, it had not yet started snowing in Siberia. I could see no sign of human life, and the view rolled away in an otherworldly blend of mountains, streams, and forests to an endless horizon. I shook my head and it brought to mind Tolkiens gloom-filled Mordor.

My neighbor woke up and smiled at me sleepily.

Good morning, Robert! he said, pronouncing my name in a slow, Russian accent.

Sergei was a Muscovite salesman of my age who was flying to the outer limits of civilization in order to sell safety clothing to the local mining industries. We had met the night before when we boarded the plane in Moscow. His English was almost as poor as my Russian, but with the help of a dictionary, I had managed to explain to him that I was flying to the far-eastern Siberian city of Magadan with only a one-way ticket because it was my intention to return home to England by bicycle.

But Robert, he had reasoned with me, there is no road from Magadan; you cannot ride a bicycle.

I explained that I had reason to believe that there was a road, though not many people used it these days.

Alone? he asked, pointing at me.

No, I will be riding with a friend.

One?

Yes, just one friend, I nodded, hoping that my friend, Al, would arrive, as planned, in three days time.

Sergei still looked unconvinced and pointed outside:

Holodna, Zeema?

Holodna was a word that I would grow accustomed to hearing over the next few months. It meant simply cold. Zeema meant winter. I had to agree with Sergei that although the weather did not look too bad right now, the infamous weather of Siberia would not stay away for much longer. The road we would have to follow, the only road that existed, would take us past the coldest inhabited place in the world.

I tried to bolster my case by explaining to Sergei with hand gestures toward my arms and legs that I had lots of very warm clothes, though I left out the fact that because the trip was self-funded and without sponsorship, I was on a tight budget. Most of my clothes and equipment had been bought at slashed prices on eBay. In reality, I was not at all sure if they would be up to the job. This was especially the case for my enormous Royal Mail over-trousers that I had bought for fifteen dollars. They were several sizes too big and probably more suitable for the midmorning drizzle of London than the long, hard winter of Siberia.

Of even greater concern was the tent. It had been given to us by a kind lady who had taken an interest in the expedition after seeing our website, though we had never actually met her. We had not yet tried putting it up, but it was free, so it seemed like the ideal option at the time. Furthermore, we would have neither a satellite phone nor a global positioning system (GPS) and, in fact, no backup whatsoever. I also did not admit to Sergei that the coldest temperature I had experienced prior to this was during a camping weekend in Scotland, nor that my main fitness training had been in the form of badminton matches against my colleague Paul after work. Because I was not entirely sure why we were setting off at the start of winter (other than it was when we were ready to start), I just told Sergei that the winter would be an exciting and beautiful time of year to see Siberia.

How long? he gestured a bicycling motion.

One year, I said confidently. In fact, though I did not know it at the time, the ride would take several times longer than this and, for the vast majority of it, I would be on my own.

We dropped below the cloud level and, as the land rose to meet us, the broad, dark shapes converged as distinct mountains. They were shrouded in sparse, green forest. I felt a twinge of claustrophobia as we landed on the runway.

Inside the small, gray terminal building, the young lady at the immigration counter stamped me through but did not return my smile. I collected my bicycle and bags and loaded them onto a 1970s-style bus outside. The gruff driver revved the engine, lit a cigarette, and drove out onto the road. I was excited that I would soon be arriving in the city from where I would begin riding, but I was also daunted. Magadan did not have a good reputation with the Russians. Half a century beforehand they had nicknamed it the Gateway to Hell.

HOW WILL I DIE?

If you were to die right now, how would you feel about your life?

B RAD P ITT , F IGHT C LUB

M AGADAN IS SITUATED ON a small neck of land that stretches feebly southward into the Sea of Okhotsk from the colossal landmass of far-eastern Siberia. Making use of this natural harbor, the city was built as a port to enable access to the hinterlands. The bus wound down the valley toward it, amid an expanse of gently sloping, uninhabited hillsides. I could see that some of the pine trees had already dropped their needles in anticipation of winter. We emerged out of the valley, and I saw an old power station standing against the bare hills. With its two giant, smoking chimneys, it reminded me of a disgruntled old man. Revving into the city, we drove past lines of rectangular, mass-produced, Soviet-style flats, and before we pulled into the bus station, I caught sight of a stagnant display of half-sized MiG fighter planes stuck on shafts. It felt as if I had suddenly fallen back through time into the dark world of Cold War rivalries.

Next page