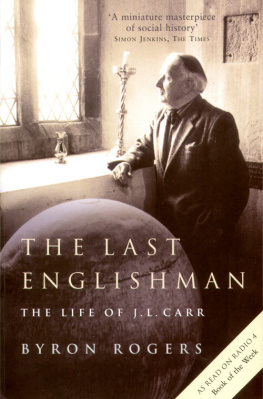

Byron Rogers is also the author of An Audience with an Elephant

(Very funny but also beautiful and moving New Statesman),

The Green Lane to Nowhere (The most beautiful book in recent memory

about the Midlands Daily Express) and The Bank Manager and the Holy Grail

(Completely mad and very charming Jeremy Paxman, Observer Books

of the Year). The Last Englishman was chosen by D.J. Taylor in

the Independent as one of the ten best biographies.

All are published by Aurum. He lives in Northamptonshire.

A biography that is as gentle and winning as Carrs own best work The Times

There could be no more sympathetic biographer than Byron Rogers, who shared Carrs love of Northamptonshire and knew his strangely secret subject as well as anyone. Indeed, the two friends natures complement each other nicely.

Rogerss Welsh warmth, humour and professional journalists nose for a good

story provide the perfect accompaniment to Carrs closed-up character underneath

the serious, blunt, awkward, formidable, decent, wry, dryly witty exterior

Hugh Massingberd, Daily Telegraph

You cant exactly say that they dont make them like J.L. Carr any more, for

Rogers is, you feel, a little like him or at least sympathetically attuned to his

capacity for eccentricity. It is very pleasing that one original should be given the

opportunity to salute another. Its not a typical biography. And how, you wonder,

could it have been? Nicholas Lezard, Guardian

This book is a powerful study of sheer character, of a man funny, innocent and strong, as incapable of sycophancy as of subservience Simon Jenkins, The Times

Riveting In his friend Byron Rogers, Carr has found the perfect portraitist.

There is, thank goodness, no wearisome accumulation of detail or slavish

slogging in the footsteps of Greatness, but rather a succession of shafts of light,

each illuminating a different aspect of this extraordinary man The Tablet

A brilliant biography Western Mail

To Jo

J.L.Carr lives in England.

His idea of autobiography, on the dust-jacket of the American edition of A Month in the Country.

LIST OF CONTENTS

PEOPLE TALKING

Id known him forty years. I went to his funeral and I knew two people there. Who has a funeral like that? Its only now that hes dead that Ive come to realise how odd he was. He collected people but he kept them in separate boxes, and I should know. He collected me. I had my box.

C HRIS F IDDES, painter

You never knew what hed take up next or what his attitude to it would be.

J OHN B URDEN, librarian

He married a nice woman, had a nice son, lived in a nice house and had all the trappings of modest success. But you still had the feeling he was thinking, Ill show them.

J OHN S TEANE, grammar school headmaster

U NTIL I STARTED WRITING this book, I had little idea of what biography involved: not for the reader (Id read enough of the things, and they seemed fairly straightforward), but for the writer. Jim Carr was fascinated by the situation of the secret sharer he had found in Conrad and used it more than once, but this is what the biographer must become, rummaging in private letters, reading things that until then only one other, the writer, has read, so the point comes where he knows more about a family than their own children. Biography is a huge intrusion.

A ghostly, uninvited guest out of the future, I have been with the boy on his first day at school when the bully, confronting him, asked whether he believed in God, and he lied and said No; Carr, in all his versions of the incident in fiction and journalism, never managed to admit that this is what he said. I have shared the footballers joy at the last minute goal (it was 1930, and an amazing goal); I have stood with him looking up at the lit windows of a womens hall of residence from which the love object has not written in months. I have shared a young mans silliness; I have been to the Wild West with him, and to war; and, a thing in darkness, I have peered in at the windows of that most secret of institutions, another mans marriage. In life I was there with him near the end, the world resolved into a vast bed and a lamp. For I knew this man.

And if biography is an intrusion, think how much more of one it is then, especially when that man confided in no one and a year before his death burned all his diaries but would never say why. Then it is like opening door after door, nervous of what you might find, for these were rooms into which you were never invited, only the house is empty, its occupants gone.

For having said I knew J.L. Carr, I never really knew him; I dont think anyone did. You saw as much of Jim as he was prepared to show you, commented the writer Tim Heald. There was a whole lot more, but he was buggered if he was going to show you that. Jim Carr, said his old friend the painter Chris Fiddes, who later illustrated many of the little books he published, had an iron sense of what was your business and what was not.

But I approved of him: I approved of the values of a man who loved churches and history and cricket, who could quote poetry and the St James Bible by the yard, and believed in Magna Carta for Gods sake, invoking this as a defence in a court case in his last book. If Carr had any illusions, these had to do with the commonsense and innate decency of ordinary Englishmen; his heroes were forgotten men, like those in the early seventeenth century who were ridden down when they spoke out against the enclosing of common land by the rich.

He hated London, big business, public men, all bureaucrats, experts and TV producers, many of whom receive their comeuppance in his novels. In these, if he spoke for anyone, it was for what Chesterton called the Secret People, the people of provincial England, a world, wrote D.J. Taylor in a review of Carrs last book, kept alive not only by human decency, but by frustration. And, in his case, by the past. He understood the past; he knew what footsteps had led up to him, and, in his odd way, was the most moral writer of his time.

That is why I have called this book The Last Englishman, as Christopher Hill called his biography of Cromwell Gods Englishman, for it was the Englishness I kept encountering in this awkward, formidable, intensely decent (how that word recurs), intensely serious man, who laughed apart and, one of his friends recalled, never said an unconsidered thing. While there was no frivolity in him, there was repression: of the one moment of female nudity in the books (it occupies a single paragraph in A Season in Sinji, and even then is glimpsed through a window), he wrote in his annotated copy, I copied this from a picture in the National Gallery. And there was confusion, for nothing quite added up. As the historian John Steane said, who had met Carr when headmaster of Kettering Grammar, Of course hed have been a Cromwellian, but hed also have been a member of Lauds church, drawing the altar rails as he knelt in his pew. He was spending his old age, Carr once assured his readers, carving at no charge mediaeval effigies in limestone to replace those knocked from niches during the Reformation, which would have horrified his forebears more than the nudity. He noted carefully the first time he saw a Welshman, and thereafter spent most of his holidays in a solitary caravan in a field in Wales, watching them from a distance. I thought of him as the last of a species.