Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2011 by Dennis B. Downey and Raymond M. Hyser

All rights reserved

First published 2011

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.103.2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Downey, Dennis B., 1952

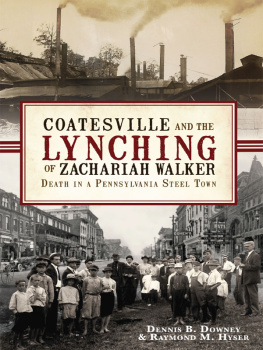

Coatesville and the lynching of Zachariah Walker : death in a Pennsylvania steel town / Dennis B. Downey and Raymond M. Hyser.

p. cm.

The present work is a substantial revision of our earlier work entitled No Crooked Death, published by the University of Illinois Press in 1991--Intro.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-280-9

1. Lynching--Pennsylvania--Coatesville--Case studies. 2. Walker, Zachariah, d. 1911. 3. Trials (Murder)--Pennsylvania--Coatesville. 4. Coatesville (Pa.)--Race relations. I. Hyser, Raymond M., 1955- II. Title.

HV6462.P4D67 2011

364.134--dc22

2011012905

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To our families

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Working on this project over a span of more than two decades has been a collaborative endeavor in every sense of the word. Many people have helped us along the way. Grateful appreciation is here recorded.

Barbara Erdman and Maggie Eichler offered essential help throughout this project, as did Pamela Powell and the Chester County Historical Society. Coatesville residents Eugene DiOrio and Ted Reed played a critical role in securing permission to reproduce images. Charles Hardy III of West Chester University offered wise counsel and astute judgment throughout the preparation of this manuscript. Hannah Cassilly and the editorial staff of The History Press have been patient and professional at every turn.

I also recall several wonderful conversations with Lee Carter, a retired steelworker with an abiding respect for local history. Millersville University provided generous financial support, as well as a stable environment in which to think about and do history. I also remember with great gratitude the intellectual friendship offered by the late William D. Miller and the late Monsignor William A. Kerr, both of whom valued the clarification of thought in its many forms. Finally, I express again my love and devotion to Traci and our children, Bernie, Maggie, Kara, Thomas and Anna.

DBD

I wish to thank my colleagues at James Madison University for their support and guidance over the years. My children, Kelsey, Marshall and Christopher, made me see the world differently through their boundless joy and love. The greatest debt is owed to Pamela, whose generous portions of love, patience and good humor were more than anyone could ask.

RMH

INTRODUCTION

During the first week in August 1911, an itinerant African American minister preached a religious revival at the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Coatesville, Pennsylvania. His name was Prophet Andrew Jones, the colored prophet, according to the local newspaper, and nothing is known of him except this: he claimed that God had ordained him with the gift to foretell the future. Jones informed the all-black congregation that he had correctly predicted such diverse tragedies as the Johnstown flood, the Baltimore fire and the San Francisco earthquake. Now, in the closing moments of his weeklong crusade, the evangelist said he had a special message for the black citizens of Coatesville. A great misfortune was about to fall on the town, he predicted, and in this time of trial and tribulation they would do well to remember that the meek shall inherit the earth. The Coatesville Record reported that Jones counseled local blacks to make no attempt at violence although they would be sorely tested.

Little more than a week later, on a warm Sunday evening, a black man named Zachariah Walker was murdered on the edge of town, burned alive as a crowd of several thousand people looked on fascinated by the spectacle. Three times he attempted to free himself, only to be pushed back onto his funeral pyre by young men closest to the flames. No one stood against the mob, and some spectators waited hours for the ashes to cool so they could retrieve souvenir bone fragments. Walkers last words were a mournful plea to his captors: Dont give me no crooked death because Im not white. The next morning, young boys sold pieces of Walkers body on downtown street corners.

Not surprisingly, the death of Zachariah Walker focused national and international attention on this Pennsylvania steel town and its nearly twelve thousand inhabitants. Commentators familiar with the commonplace nature of racial lynching in turn-of-the-century America remarked on the brutal manner of death and on the oddity of this incidents geographic location in a northern industrial town rather than the American South. Former president Theodore Roosevelt was among the host of critics who rebuked townsfolk for their failure to prevent the lynching. In the midst of blistering criticism, Coatesvilles residents joined ranks in what a county judge criticized as a conspiracy of silence that thwarted the efforts of prosecutors to bring the perpetrators to justice. On the first anniversary of the lynching, social reformer John Jay Chapman traveled to Coatesville to conduct a memorial service, commemorating what he called an American tragedy. No more than a half dozen people attended the gathering.

Published on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Zachariah Walkers death, this narrative seeks to tell the story of what happened and why it is of enduring significance. In some respects, the present work is a substantial revision of our earlier work entitled No Crooked Death, published by the University of Illinois Press in 1991. That earlier book, no longer in print, represented a more detailed and scholarly approach to the subject, seeking to place the Coatesville lynching in the context of the developing scholarly discourse on lynching and racial violence in American history. As a scholarly case study, No Crooked Death has held up well and received its own notoriety over the past two decades.

In this revised and substantially altered text, however, we have attempted to update and make more accessible to a general audience the compelling and controversial saga of Zach Walkers brief life and tragic death in a Pennsylvania steel town. We have retained the basic narrative found in No Crooked Death, but we have omitted intentionally some of the detail and recast portions of the larger contextual analysis while retaining the sense of historical drama found in this individual historical event. Local controversy surrounding the 2006 dedication of a historical marker, which we discuss in the Afterword, provides fresh evidence of how the death of Zachariah Walker has been interwoven in the fabric of community relations in Coatesville and the surrounding area.

Ask big questions of small places, historian Charles Joyner once advised. As in the earlier work, that is our intention in this version of the story. In many respects, the lynching of Zachariah Walker is freighted with meaningfor the residents of Coatesville and for others interested in the American past. Walkers death at the hands of a mob typifies what historians now call a spectacle lynching. Mobs of thousands watched grotesque rituals of violence that were often accompanied by unusual and stylized acts of mutilation and human desecration. Not only did some bystanders wait hours to retrieve relics, but others took photographs to remember the event long after it had passed. Perhaps Michael Pfeifer put it best when he observed that lynching was a form of rough justice that reveals important features of individual and community sentiments on matters of race and rights. Lynching was a crime, a form of extralegal violence that rarely was punished. While its proponents could defend the practice as understandable and even necessary, its critics more often condemned the practice of mob violence with impunity as a betrayal of democracy and any sense of decency. Too often in the history of lynching, due process under law received little respect as the mob stirred to action. Not too many years before the Coatesville incident, Mark Twain struck at the heart of the matter in an essay entitled The United States of Lyncherdom, when he castigated those who lacked the moral courage to stand against the mob.

Next page