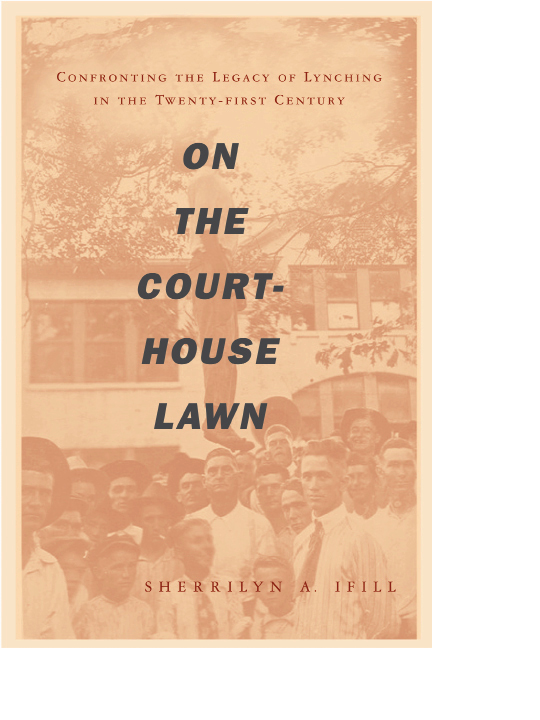

ON THE

COURTHOUSE

LAWN

Confronting the Legacy of Lynching

in the Twenty-rst Century

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

BEACON PRESS, BOSTON

For N, A, and J,

who make me dream of a better world,

and for Ivo,

with whom I share all my dreams

Contents

Introduction

The experiences that moved me to write this book are sprinkled over my seventeen years as a civil rights lawyer. First, at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the nations premier civil rights law rm, and later as a law professor, I have represented communities struggling with the problem of race. As a civil rights lawyer, my job has been to translate those problems into cognizable legal claims. Early on, I discovered that this was no easy task. My clients claims of discrimination often represented the culmination and crystallization of decades, sometimes centuries, of halting, painful, and mostly unsuccessful attempts to negotiate a place of dignity, equality, and power within their communities. And in relating this complex and painful history to me, my clientsfrom Oklahoma to Marylandinevitably told me something about lynching.

Until recently, few Americans, black or white, fully realized the widespread and pervasive reality of lynching in our nations history. Now, thanks to some excellent books published in the last few years and an exhibit of lynching photos that has toured the country since 2001, those who want to know about this dark chapter in American history know that during the rst half of the twentieth century lynching was, as historian Frank Shay observed, as American as apple pie. Even more powerful, the lynching of James Byrd in Jasper, Texas, in 1998 and that of Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyoming, a year later compelled blacks and whites in communities throughout the United States to recall their own history of lynching. From Utah to Minnesota to Florida, long-repressed memories of this uniquely American form of terrorism were fanned into ame.

But as the collective memory of systematic racial terrorism awoke throughout the country, communities found that no formal mechanisms existed to assist blacks and whites in coming to terms with the legacy of lynching. Some discovered that talking about lynching was a surere way to surface long-simmering racial conicts. President Clintons call to have a national conversation on race in 1994 and his appointment of the One America Commission to explore the issue of race might have provided an opportunity to face this difficult history, but lynching was strangely absent from the commissions agenda, and that bodys worksome of it quite impressivewas largely unknown to most Americans.

In the course of my work, I have been amazed to discover how often and how pervasively racial violence gures into the history of small towns and cities throughout the United States. For example, I rst heard about the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, in which whites burned down the prosperous black section of town known as the Black Wall Street, from clients I represented in a voting rights case in Oklahoma and Tulsa Counties in 1991. Although I included allegations about the Tulsa Race Riot in my legal complaint in that case as evidence of the history of discrimination in Tulsa County, it was difficult at the time to nd conrmation that this racial pogrom had ever happened. Because of the work of lawyers and historians, and because of the courage of elderly survivors of the Tulsa Race Riot, we now know about this act of racial terrorism and about the deliberate attempt by some whites in Tulsa to cover it up.

I learned about the Maryland lynchings in almost the same way. I was looking into the history of discrimination on Marylands Eastern Shorea body of land on the eastern side of the Chesapeake Bay that connects Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia. The clients I represented were African Americans who had been the victims of discrimination in state highway siting decisions in and around Wicomico County, Maryland. It took a while before I understood that there had been two lynchings, one in 1931 and another in 1933. My clients talked only about one, melding the facts of the two lynchings together in a single gruesome and terrifying story. And it took a great while longer for me to learn that in that same two-year period several other black men had narrowly averted being lynched, and that lynching had a long and powerful history on the Shore that extended back to the nineteenth century.

Two things struck me early on about the way blacks and whites talked about the lynchings. First, I was taken with how present the lynchings were for blacks. This should not have been surprising. As writer Ishmael Reed recently observed in the New York Times , Stories of lynchings are a key feature of the black oral tradition. Even blacks in northern states, where lynchings rarely occurred, can share vivid stories about lynching. This is largely because of the courageous reporting in black papers like the Chicago Defender , the Amsterdam News , and the Baltimore Afro-American during the 1930s and 1940s, which enabled black readers nationwide to experience the horror of lynching and its violent aftermath. When Mamie Till, the mother of fteen-year-old Emmett Till, who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955, insisted on an open casket for her sons Chicago funeral, the ten thousand blacks who streamed by his casket were overcome by the hideous reality of violent white supremacy, reected in the mangled face of the fteen-year-old boy. In effect, black Americans share a kind of communal memory of lynching that is not bound by region or by time.

So although the Eastern Shore lynchings had occurred more than a half century ago, for many African Americans the lynchings were a dening moment in their racial history. Blacks were particularly eloquent about the fact that hundreds, maybe thousands, of whites had watched the lynchingssome participating, some cheering, some shocked, but none intervening. It was not so much the eight or nine men who dragged twenty-three-year-old Matthew Williams from his hospital bed to hang him on the courthouse lawn in Salisbury in 1931 or the twenty who broke down the door of the jail in Princess Anne to hang, drag, and burn twenty-seven-year-old George Armwood on the street in 1933 who were xed in the minds of the blacks I spoke with. It was the participation or presence of average whiteslaw students, businessmen, waiters, shopkeepers, laborers, police officers, and most of the Wicomico High School football teamthat blacks remembered. For many blacks on the Shore, this was the lesson of lynching passed down from generation to generation: ordinary whites were not to be trusted.

Most blacks with whom I spoke had heard about the lynchings when they were children, eavesdropping on grown folks hushed conversations. So vivid were these stories that these children, now grown up, could describe the lynching in great detail and with, I discovered, surprising accuracy. Edward Taylor, a retired school principal and later county councilman in Wicomico County, had so deeply internalized the description of the 1931 lynching of Matthew Williams hed heard as a child that he grew up believing that hed actually seen the lynching. It was not until he was a grown man that he realized he was not even born when the lynching occurred.

More than any other incident of racial violence, lynching evokes particularly resilient memories in African American communities. Orlando Patterson, in his searing study of lynching, Rituals of Blood , has suggested that it is the memory of the smell of burning esh that stays encoded in the memory, longer even than the visual image of the lynched body. Walter White, the great antilynching crusader and NAACP president during the 1930s and 1940s who was so fair-skinned that he was able to pass as a white man and observe the aftermath of several lynchings, said that it was the participation of white children in lynching, as torturers or as excited observers, that seared the horror of the act into his brain.