RACIAL TERRORISM

RACE, RHETORIC, AND MEDIA SERIES

Davis W. Houck, General Editor

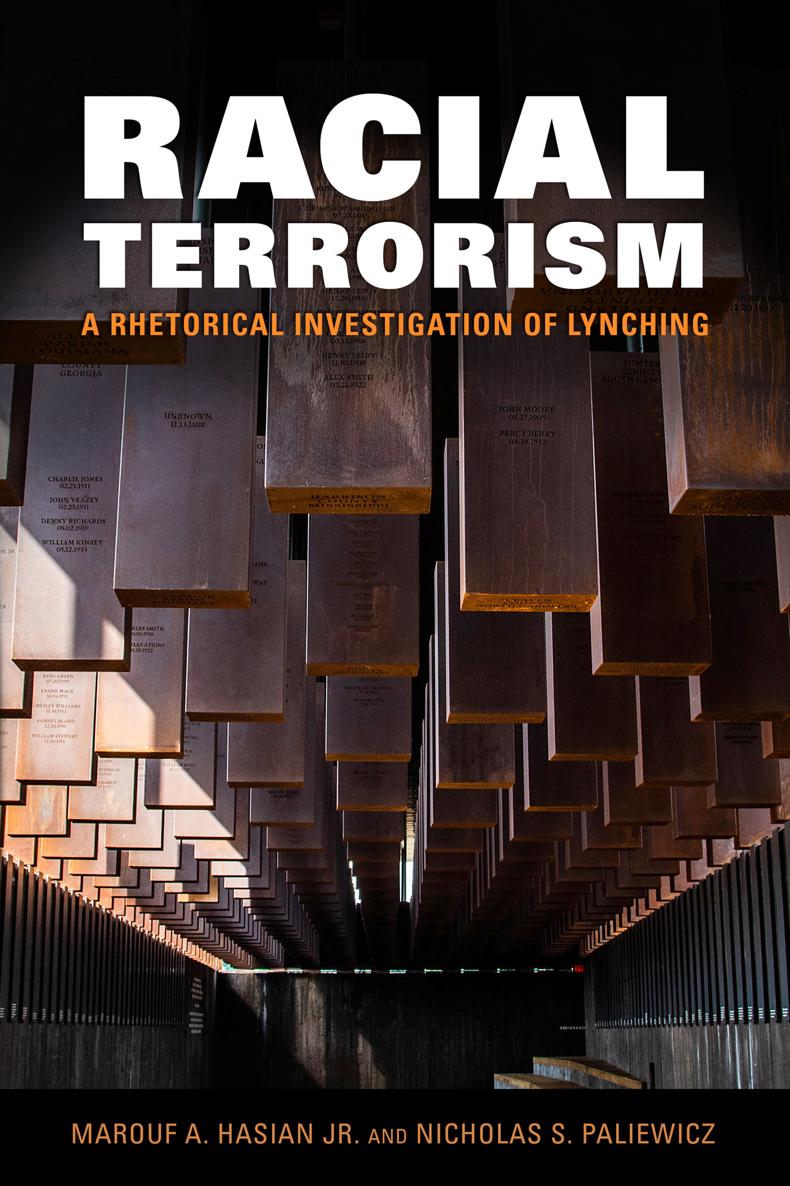

RACIAL

TERRORISM

A RHETORICAL INVESTIGATION OF LYNCHING

Marouf A. Hasian Jr.

and

Nicholas S. Paliewicz

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson

The University Press of Mississippi is the scholarly publishing agency of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning: Alcorn State University, Delta State University, Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, Mississippi University for Women, Mississippi Valley State University, University of Mississippi, and University of Southern Mississippi.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Photographs courtesy of the authors unless otherwise noted

Copyright 2021 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Hardback ISBN 978-1-4968-3174-3

Trade paperback ISBN 978-1-4968-3175-0

Epub single ISBN 978-1-4968-3178-1

Epub institutional ISBN 978-1-4968-3173-6

PDF single ISBN 978-1-4968-3176-7

PDF institutional ISBN 978-1-4968-3177-4

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work would not have been possible without the support of several individuals from University Press of Mississippi and our respective universities at the University of Utah and the University of Louisville. We would first like to thank Vijay Shah for his sustained interest in our project, not to mention all of his encouragement, as former acquisition editor at UPM. Although Vijay is no longer with this press, there is no doubt that this text would not have been possible without him and his advocacy for this project. At UPM, currently, we are also grateful for all the assistance from such folks as Emily Bandy, Shane Gong Stewart, Todd Lape, and Jordan Nettles. We also could not have asked for a better copyeditor than Norman Ware. Normans meticulousness and care truly enhanced the quality of this monograph. We are also grateful for the arduous work of our indexer, Kristin Kirkpatrick.

At the University of Utah, the authors thank everyone in the Department of Communication and Dean of the College of Humanities, Stuart Culver. The authors are also appreciative of all of the support from everyone in the Department of Communication at the University of Louisville and the interim dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, David Owen. We are particularly grateful for the financial assistance from UofLs Communication Department during critical times in the history of this project, which made possible both a pilgrimage to Montgomery in 2018 and, crucially, this books index. We are specifically grateful to Al Futrell (chair), Kandi Walker (vice-chair and former interim chair), Keneka Cheatham (Program Coordinator, Sr.) and office staffKatie Cross Gibson and Lauren Mayin addition to Kamla Gant (UBM) for aiding this project in these ways and others.

Personally, there are too many people to thank, but a few of those that must be named for one of the authors include Steve Paliewicz, Lisa Fleet, and Cory and Ryan. The most important kind of support for that same author has come from Banrida Wahlang and sweet baby Amora.

RACIAL TERRORISM

INTRODUCTION

Understanding the Stakes Involved in the EJIs Lynching Remembrances and Historiographies

FOR MORE THAN A CENTURY, AMERICAN LEGISLATORS HAD TRIED, AND FAILED, TO pass federal anti-lynching legislation. All of this began to change when, on December 19, 2018, US congressional leaders finally passed the nations first anti-lynching actthe Justice for Victims of Lynching Act. For the first time in US history legislators, representing the American people, were willing to classify lynching as a federal hate crime.1 Introduced by Senators Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, and Tim Scott, this particular anti-lynching bill achieves what advocates such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were unable to do for over a century. Between 1882 and 1968, Congress weighed in on nearly two hundred anti-lynching bills, and not one of them passed. In February 2019, the US Senate unanimously backed the anti-lynching bill,2 and it was said that the bill stood a strong chance of making it to President Trumps desk.3 This particular federal anti-lynching bill contains language that recounts the brutal American history of racist lynchings, and then makes injuring or killing someone because of race, color, religion, or national origin by two or more people a federal crime punishable by up to life in prison.4

However, in the middle of all of the celebration of how the nation seemed to be making headway regarding consciousness raising about historical lynchings, as evidenced by the bipartisan support of the Justice for Victims of Lynching Act, President Donald Trump, in October 2019, during heating argumentation preceding the House of Representatives vote on impeachment proceedings, tweeted that all Republicans needed to remember that they were witnessing his lynching.5 Kamala Harris, who had cosponsored the bill and was still in the running for the 2020 US presidential election, responded to Trumps tweet by noting that lynching was a reprehensible stain on this nations history, and that the presidents attempt to invoke the pain and trauma of lynching to whitewash his own corruption was disgraceful.6 Cory Booker chimed in, arguing that lynching was an act of terror used to uphold white supremacy and that perhaps the American president needed to try again.7

As the chapters of this book will demonstrate, this has not always been the case. The uncontested passage of this antifederal legislation by the House and Senate stands out even more when scholars and readers take into account the darkness of so many archival recordings of lynching incidents that can be found in tattered newspapers and in local libraries across the nation.

For years, organizations like the NAACP, led by activists like James Weldon Johnson and Walter Francis White, had done everything to try to convince the American nation that lynchings were immoral, illegal, and dehumanizing. The members of the NAACP, as Marlene Park explained, used many different tacticspress releases, publications, rallies, pickets, conferences, marches, lawsuits, and even art displaysto get across to audiences the graphic horrors of lynching.8

This book focuses attention on several key social agents who played vital roles in the public and legal consciousness raising that led to the passage of the Justice for Victims of Lynching Act in the Senate. We will argue that the labor of a lawyer named Bryan Stevenson, the work of an organization called the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI),9 and the efforts of curators at Montgomery, Alabamas new Legacy Museum all contributed to the formation of a rhetorical culture10 that helped set the stage for the serious consideration of this 2018 federal anti-lynching legislation. The EJI and their supporters, along with many interdisciplinary scholars who were worried about present-day carceral practices, would become twenty-first-century activists in the struggle for what some are now calling the New Reconstruction.11

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION