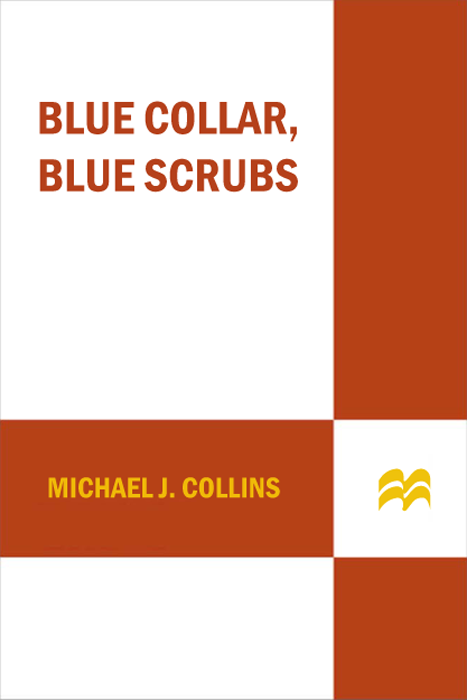

Also By Michael J. Collins, M.D.

Hot Lights, Cold Steel

Blue Collar, Blue Scrubs

The Making of a Surgeon

Michael J. Collins, M.D.

ST. MARTINS PRESS  NEW YORK

NEW YORK

BLUE COLLAR, BLUE SCRUBS. Copyright 2009 by Michael J. Collins, M.D. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Chapter Twenty adapted from A Childs Pain, originally published in JAMA (1997; 277[21]:1668). Copyright 1997 American Medical Association. Used by permission.

www.stmartins.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Collins, Michael J., M.D.

Blue collar, blue scrubs : the making of a surgeon / michael J. Collins, M.D.1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-312-53293-2

ISBN-10: 0-312-53293-8

1. Collins, Michael J., M.D. 2. OrthopedistsUnited StatesBiography. 3. SurgeonsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

RD728.C64A3 2009

617.092DC22

[B]

2008046213

First Edition: June 2009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Pattithen, now, and always

INTRODUCTION

Have you ever noticed that two plus two doesnt always equal four? It didnt for me, and I guess thats what this story is all about.

Im a surgeon now. I spend my days in quiet, sterile operating rooms replacing knees and repairing rotator cuffs. A hard day in the hole would kill me. But back then I was a laborer. I spent my days breaking concrete and throwing rocksand I liked it. The time would come when all that digging and lifting and breaking and throwing would be too muchbut not then. Then it was fun. It was fun to push ourselves beyond all reasonable limits. It was fun to have some strutting, bellowing foreman threaten to fire our asses if we didnt break out some insanely long section of concrete in the next twelve hours.

Wed grumble and curse. Wed complain that this was typical Scalese slave-driving bullshit. Wed say nobody could break out that much concrete in one day. What did they think we were, a bunch of fucking mules? But somewhere, deep inside, we liked it. We liked being given unreasonable, outrageous tasks. Nothing was too much for us; and when they told us to break out three thousand feet of concrete in one day, we understood they were paying us a compliment: nobody could break out that much concrete in one daybut we could.

Wed kick the watercooler and wed say Fred could kiss our asses, but all the while wed be pulling on our gloves, rolling our shoulders, and eyeing that long stretch of concrete. Bring it on, wed think. Bring it on.

Twelve hours later, our forearms would be scratched and bleeding from being ground all day against the broken slabs of concrete. Our T-shirts would be sopping wet and tattered. Our ears would be ringing from twelve hours stooped down next to the jackhammer. We would be stretched out in the grass, boots off, drinking beer, looking back on the seemingly endless expanse of concrete we had just broken out, and thinking we had the world by the balls.

Thats what I miss about those days. Its something my friends and fellow doctors can never understand. All they see is the drudgery, the mindless slaving labor, the subjugation of the spirit. But they dont realize how liberating it can be to train your body, to make it so strong that labor enthralls it and quickens your life impulses so that all that work becomes as nothing, becomes the fuel that fires your life, that makes it worth getting up in the morning to laugh and drink and feel your muscles. Sure, somewhere inside you know its temporary. You know you are dipping into your reservoir of youth and throwing away a little more of it each day. But that reservoir seems so vast, so inexhaustible. You know there will be a day of reckoning, but until that day comes

I suppose if you had asked me what I was doing, I wouldnt have had an answer. I lacked what my college professors used to call Critical Awareness. I was about as introspective as a rebar. I worked breakout because I was good at it, because it paid well, but most important, because it told me things I wanted to hear. It told me I was young. It told me I was strong. It told me I was alive.

But toward the end it started telling me other things, too. Things I was not ready to hear. Jesse and JT and Angelo, guys who had been around for a while, they could hear it all too plainly. It fairly shouted to them. But as yet it only whispered to me. It whispered that, yes, I was young, but youth is fleeting. Yes, I was strong, but strength is illusory. Yes, I was alive, but, louder every day, it whispered that I was going to die.

And on that hot summer day when I finally heard that whisper, it hit me like a twenty-pound sledgehammer. And at that moment I knew that if I ever wanted to accomplish anything important in life, Id better get going.

CHAPTER ONE

I n the final stirrings of the night, the door opens and Im back in the hole, throwing rocks. Ive filled another truck with them. But Angelo isnt taking them to the dump. Instead, theyre going somewhere else.

I roll over and flail again at the alarm clock. Its 5:00 A.M. Im late and I know it. I groan, push myself up, and run a hand across my face.

I throw off the blanket, struggle to my feet, yank on my jeans, and throw a T-shirt over my shoulder. I sleep on the floor in the attic of my parents house, and as I pad downstairs in my bare feet, the house is quiet. My parents and seven younger brothers wont be up for another hour or two. As I pass Tims room, I bump open the door with my hip and flip on the light. Tim is lying on his right side, sheets twisted around him. I call his name and tell him I had fun with Diane last night. Diane is Tims girlfriend.

I think I finally convinced her she is going out with the wrong brother, I tell him.

Tim yawns, pulls the sheets over his head, and tells me to keep dreaming. What girl in her right mind would go out with you? he asks.

I scratch my head, realize Tim is probably right, and turn off the light.

Down in the kitchen, Shannon is curled up in the corner. She gets slowly to her feet, stretches, and dutifully shuffles over. I bend down, scratch her behind the ears, and tell her she is beautiful. Shannon yawns and goes back to the corner.

I wolf down a couple bananas and pour a glass of orange juice. As I am drinking the juice, I grab eight slices of bread, lather four with peanut butter, four with jelly, then fold them into sandwiches and toss them in a paper bag. In the corner of the icebox I find a boiled potato, two apples, and a plastic bowl of macaroni and cheese. I throw them in the bag, too. I fill my old, quart-glass Coke bottle with water, grab my boots from the back door, and trot out to the car. I toss my boots and lunch on the seat next to my hard hat, plop down into the drivers seat, and start the ignition. Blue-gray smoke belches from the exhaust as the old Pontiac rumbles into life.

It is ten to six when I jam on the brakes outside the ten-foot-high chain-link fence that surrounds the Vittorio Scalese Construction Company. The morning sun is streaming down Grand Avenue. Bakery trucks and newspaper vans are dragging long shadows behind them as they head east into the city. I grab my hard hat and lunch bag, slam the door of the Pontiac, and sprint through the gates past the large pile of wooden stakes that dominates the center of the yard. Behind the stakes, a thirty-foot-high shed with a corrugated iron roof shelters a table saw, more stakes, and two enormous piles of black dirt.

NEW YORK

NEW YORK