To Harry

Contents

P REFACE

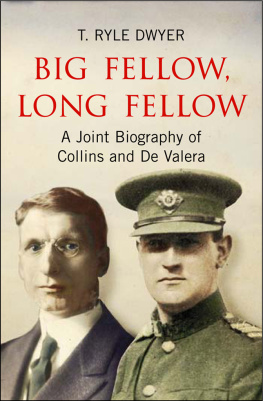

M y interest in Irish history developed quite by chance at university in the United States in 1966. While taking a course on European history between the world wars at the University of North Texas, I chose to write a term paper on the Irish Civil War. I had grown up in Ireland from the age of four and received all my primary and secondary schooling in Tralee, but I was intrigued to learn that the partition question had essentially nothing to do with the Treaty split between Eamon de Valera and Michael Collins that was largely blamed for the ensuing Civil War.

As this was not a period of history that was covered in Irish schools in either the 1950s or the early 1960s, I became fascinated with the subject and later wrote a Masters thesis on the Treaty negotiations, and a doctoral dissertation on relations between the United States and Ireland during the Second World War. This book draws heavily on research going back over thirty years. I have already written both a short and a full-length biography of de Valera, as well as two detailed studies of his quest for national independence, and two monographs on Collins: Michael Collins: The Man Who Won the War , and Michael Collins and the Treaty .

During the course of the ongoing research I corresponded with a number of people who appear in these pages, including de Valera, Robert Barton, Sen Mac Eoin, Ernest Blythe, Geoffrey Shakespeare, and Tom Barry. I would like to acknowledge the help of the late Liam Collins who trusted me with his trunk of papers of Michael Collins, even though someone to whom he had previously loaned diaries had never returned them.

My only agenda is to tell the story as fairly and as dispassionately as I can. On all sides people succeeded and made mistakes, even though partisans of de Valera and Collins have tended to paint the period in black and white terms, whereas in reality there were many shades of grey. It was for long assumed that the two men worked closely together and trusted each other implicitly until the Treaty split, but their differences really went back much earlier.

This is a study of the parallel lives of de Valera and Collins with emphasis on how their careers intermingled and finally diverged. Their differences undoubtedly became a major factor in the split that led to the Civil War and cast a shadow over Irish politics not just for decades, but arguably for most of the century.

TRD

Tralee,

September 1998

An Unwanted and a Cherished Child

E amon de Valera was an unlikely Irish hero, much less the virtual personification of nationalist Ireland. Born in New York city on 14 October 1882, he was the son of an Irish immigrant mother, Catherine Coll, and, according to her, a Spanish father, Vivion de Valera.

Considerable mystery surrounds Vivion de Valera. According to Eamon or Edward as he was christened and called until his adult years his parents were married in New York in 1881, but there is apparently no mention of the marriage in the church records. Shortly after Eamon was born, Vivion moved west for health reasons and died two years later in Denver. If he died of tuberculosis, the mystery surrounding him would be understandable, because Irish people tended to view the disease as a kind of social plague. If spoken about at all, it was in terms of being as bad as some fatal venereal disease.

When Eamon was two years old his mother sent him to Ireland with her brother to be reared by her own family near the village of Bruree, County Limerick, while she remained in the United States. Eamon never forgot his first morning in the Coll family home a one-roomed thatched cottage, housing himself, his grandmother, two uncles and an aunt. He woke up to find the house deserted. The family was moving to a new slate-roofed, three-roomed labourers cottage nearby and nobody had bothered to ensure the child would not be frightened waking up alone in a strange, deserted house.

It has long been believed that a persons character is shaped as a child. Like any child, de Valera would have first looked to his parents for security. Never having known his father, he would have become especially dependent on his mother, and his subsequent separation from her would undoubtedly have had a profound effect on him. She remained in the United States, and the uncle who brought him to Bruree soon returned to America, to be followed shortly afterwards by Eamons teenage aunt, Hannie, to whom he had become attached. Thus the people to whom de Valera looked first for security during those formative years were in America, and it was hardly surprising that he would look first to the United States for help or security throughout his life.

His mother visited Bruree briefly in 1887, before returning to the United States, leaving the boy to be reared by her mother, Elizabeth, and her brother, Pat. Eamons mother was planning to remarry and he pleaded with her to take him back, but she refused. One can only imagine the scarring consequences of being rejected by his mother, especially when the rejection fuelled speculation about his legitimacy.

Before emigrating Catherine Coll worked as a domestic servant in a large house owned by the Atkinson family, and there was considerable local speculation that she had become pregnant by Thomas Atkinson, the randy son of the owner. It was rumoured that the Atkinsons paid for her to go to America to conceal the pregnancy. It would have been understandable for an Irish emigrant to send home an illegitimate child to be reared by her family, and even to leave the child in Ireland after she married; but it was something else for a former widow not to reclaim a legitimate child after she had remarried, and especially after she had started a second family.

De Valera always maintained that his mother emigrated two years before he was born. If this was true, Tom Atkinson could not have been his father, but no biographer has yet found evidence of his mothers arrival in the United States. Possibly nobody ever looked for this evidence, because in the last analysis it is of little historical importance. Whether de Valera was illegitimate or not is not nearly as important as the rumours that he was illegitimate, because those rumours clearly bothered him.

When he began at the local national school at the age of five, he was registered as Edward Coll. This may have been the first sign of a certain sensitivity that de Valera would later betray about his foreign background. Maybe his touchiness was the result of conditioning brought on by the attitude of his grandmother or uncle, or just the reaction of a little boy trying to fit into a society in which he probably felt rejected.

He would later recall being irritated that his uncle was known locally as the Dane Coll, which was one of those family nicknames transferred from father to son. De Valeras grandfather, Patrick Coll, used to lead prayers in the local church and as a result he was given the nickname, the Dean, which was pronounced locally as the Dane, much to the subsequent embarrassment of his grandson, who thought the nickname had something to do with the Norse invaders who had plundered Ireland a millennium before.

Saddled with supporting his elderly mother and young nephew, Pat Coll was a rather frustrated individual. He could not afford to get married and seemed to take out his frustration by being severe on the boy. He disapproved of him playing games, which he considered were a waste of time. De Valera was expected to perform various duties.

From my earliest days I participated in every operation that takes place on a farm, he later recalled. Until I was sixteen years of age, there was no farm work, from the spancelling of a goat to the milking of a cow, that I had not to deal with. I cleaned out the cowhouses. I followed the tumbler rake. I took my place on top of the rick. I took my place on the cart and filled the float of hay. I took milk to the creamery. I harnessed the donkey, the jennet, and the horse.

Next page