Start Reading

About De Valera

About Tim Pat Coogan

Reviews

Also by Tim Pat Coogan

Table of Contents

www.headofzeus.com

For Barbara and Mabel

Contents

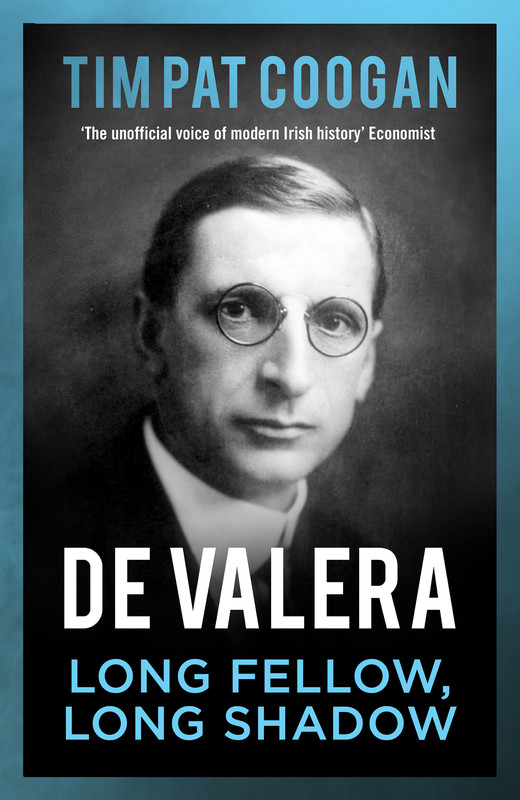

Cover

Welcome Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1: The Harsh Reality of a Nursery

Chapter 2: Marriage Through the Medium

Chapter 3: Taking the Oath

Chapter 4: Well Go Ahead with Connolly

Chapter 5: Bearding the Bishops

Chapter 6: From Lincoln Towards the White House

Chapter 7: Priomh Aire Meets Gallowglass

Chapter 8: The War from the Waldorf

Chapter 9: If They Proceed Wisely

Chapter 10: The Long Hoor v. Collins

Chapter 11: Saorstat v. Phoblacht

Chapter 12: The Cute Hoor Triumphant

Chapter 13: The Scapegoats Go Forth

Chapter 14: A Telephone Call Not Taken

Chapter 15: Every Means in Our Power

Chapter 16: Binoculars and Beal na mBlath

Chapter 17: Publicity Before All

Chapter 18: The Warriors of Destiny

Chapter 19: De Valeras Decade

Chapter 20: Pulling a Stroke

Chapter 21: De Valera Stands Tall

Chapter 22: The Unique Dictator

Chapter 23: Making for Ports, Via the Kitchens

Chapter 24: Blind Courage

Chapter 25: Gray Amidst the Greenery

Chapter 26: In the Eye of the Storm

Chapter 27: Many Shades of Gray

Chapter 28: Getting de Valera on the Record

Chapter 29: Harsh Justice

Chapter 30: De Valera Clings On, and On

Chapter 31: When Bishops Were Bishops

Chapter 32: Borne Down by What Bore Him Up

Chapter 33: The Summing-Up

Preview

Acknowledgements

Chronology

Notes

Appendix I: Articles of the Agreement as Signed on December 6th 1921

Appendix II: Document Number Two

Appendix III: Letter to Patrick Kennedy in Dept of the Taoiseach

Bibliography

Index

About De Valera

Reviews

About Tim Pat Coogan

Also by Tim Pat Coogan

An Invitation from the Publisher

Copyright

Prologue

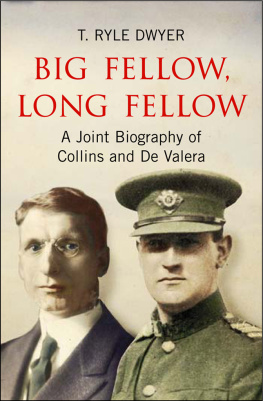

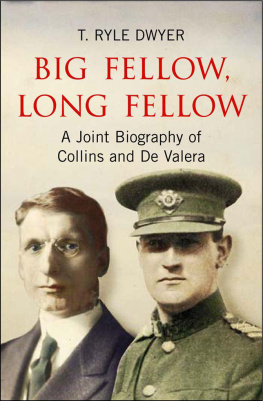

ALTHOUGH HE DIED in 1975, Eamon de Valera, generally known as either Dev. or the Long Fellow, cast a long shadow that still falls over Irish life. Quite simply the history of Ireland for much of the twentieth century is the history of de Valera. As befitted a man who sometimes seemed to model his actions on the Roman Catholic doctrine of Three Divine Persons in One God, his tangible legacies are three also: the Irish Constitution; the largest Irish political party, Fianna Fail; and the second largest Irish newspaper empire, the Irish Press Group, founded, as was so much of his political strength, on Irish America. His intangible influences can still be traced in the divisions between the leading Irish political parties, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, and in attitudes towards Northern Ireland, ChurchState relationships, the role of women in Irish society, the Irish language and the whole concept of an Irish nation. Any one of his visible creations would have been an achievement beyond the powers of most men. The three, taken together, must be accounted a rare feat indeed.

But it is perhaps in his intangible legacies that Eamon de Valeras real influence lies. The lay pontiff, the man of politics and of God, Eamon de Valera was the epitome of a land where Christ and Caesar were hand in glove. It was on his hand that the glove fitted; his hand, which, as a result, held the reins of power longer even than contemporaries such as Roosevelt, Salazar or Stalin. Yet this was not the end of his significance. In de Valeras career lies the explanation of such contemporary Irish complexities as the relationship between constitutionalism and physical force, and the ambivalence of some politicians towards violence and Northern Ireland. Approaches to education, economic planning and family law can still be measured by, with or from his policies.

Was he a Lincoln or a Machiavelli? A saint or a charlatan? A man of peace, or one who incited young men to hatred and violence? Did he seek to heal or worsen the wounds that the Irish and the English inflicted (and inflict) on each other? Was he a revolutionary or a conservative? An unscrupulous manipulator or a nice guy? The truth is that in a sense the answer to all these questions is Yes. Eamon de Valera was a law-giver who helped to bring down a civil war on the heads of his people; a revolutionary who kept his country neutral in World War II. As a result of his neutrality policy Ireland was spared the horrors of war. But his playing of the Green card of nationalism also helped to create the circumstances wherein, decades later, many young Irish emigrants found themselves denied a green card. De Valera was born in America. The money he raised from Irish emigrants helped to found and fund his Irish Press. Yet Roosevelt, who had helped him to secure these monies, became enraged at him. By the time the war was over the American Minister in Dublin, a connection of Roosevelts, was persona non grata with de Valera and his Cabinet.

De Valera was a world figure who attempted to confine his disciples to the narrowest of cultural and intellectual horizons. Many of the challenges he confronted are still troubling the peace of Ireland and of England, disturbing relationships from Belfast to Birmingham to Boston. Some of the vexing questions of the moment are directly traceable to him: the effect of part of the Irish Constitution on Northern Irelands Unionists; his philosophy of talking about God and the High Destiny of the Gael while practising realpolitik gave him control of the Irish Press and of Fianna Fail. But ownership has involved his descendants in the newspaper in some very unfortunate court proceedings. And in politics, some of those who came after him in Fianna Fail sought to profit from their opportunities by acting in ways which have spawned scandals, given rise to government inquiries, wrecked Cabinets and interfered with Irelands ability to handle a devaluation crisis. Paradigms of modern Ireland, both the newspaper and political sagas are still evolving at the time of writing.

Dev. was the greatest political mover and shaker of post-revolutionary Ireland. His towering figure continues to cast shadows that are both benign and baleful. Therefore, as a biographer, I have been conscious of two linked and major problems in the course of attempting to chart the career of this extraordinary man: first, to convey a sense of his importance to Ireland and her relationships with Great Britain, America and the members of the British Commonwealth; second, while so doing to steer between the Scylla of hagiography and the Charybdis of denigration. Practically everything of substance written about him falls into one category or the other. There is no via media where Eamon de Valera is concerned. The problem is compounded by the fact that not only did de Valera shape history, he attempted to write it also or, more correctly, to have it set down as he ordained. I have tried to evaluate him neither as a demon nor as a plaster saint, but as what he was: for better or worse, the most important Irish leader of the twentieth century. Doubtless my approach will leave me open to attack from both denigrators and hagiographers. Attempting a biography of Eamon de Valera, is, for an Irishman, somewhat like an Iranian sitting down to write about the Ayatollah Khomeini. Uneasy visions of Salman Rushdie occur. Nevertheless, though the reader may fault me for want of pietas, critical faculty or honest omission, I hope that I cannot be assailed on the grounds of fairness.

Next page