Introduction

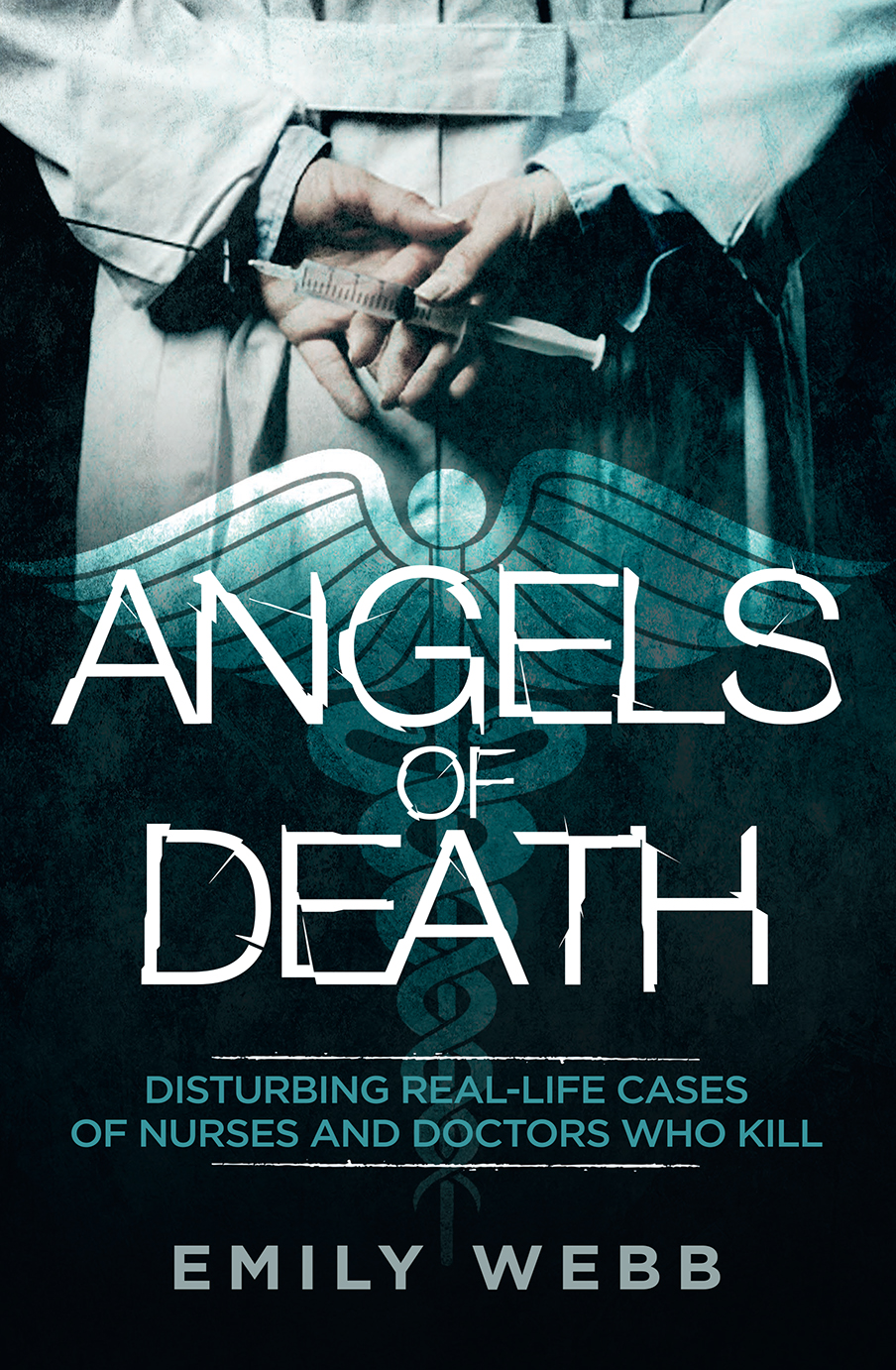

Its hard to imagine that anyone in the healthcare industry could have murder on his or her minds.

When you think of a nurse, the immediate image that comes to mind is of a caring individual who has embarked on their career for altruistic, rather than financial reasons. We all know that nurses are overworked and underpaid but in the spirit of pioneers like Florence Nightingale, they are committed to making a difference to people in need. And being in hospital or in poor health is a time of life where you are at your most needy and vulnerable.

Doctors are in a slightly different category, in that they are far better paid and have a lot of clout. Weve all heard stories of some doctors having what is referred to as a God Complex, whereby they thrive on having the power over life and death.

There is no doubt that for a few healthcare professionals this power can be so alluring that they cross the line.

Many of the cases covered in this book happened several decades ago. These days there are tighter regulations, and there is also more understanding (one would hope) about how to identify a rogue healthcare professional. As a consequence of many of the cases featured in this book, legislation and therefore hospital procedures were tightened up to try and stop healthcare professionals, such as American nurse Charles Cullen, from becoming serial killers. In the case of Cullen, a law was introduced in New Jersey in 2005 as a direct response to his killings. The act requires healthcare professionals to report if they have information about incompetence, impairment or negligence of a healthcare worker. The act also means criminal background checks of healthcare workers are mandatory if they want to work in New Jersey. (Its quite unbelievable that this wasnt the case anyway and is one of the reasons that Cullen was able to kill so many people.)

Ultimately though, no policy, law or regulation can stop a rogue healthcare killer. Whether they are mentally disturbed, angry at the world or have a genuine belief that they are doing the right thing, it is clear from the stories in this book that you cant stop someone who is hell-bent on harm. This is perfectly summed up by Dr Raj Patel, a GP who knew Dr Harold Shipman: You can legislate against a poor doctor but you cant legislate against evil.

The victims of healthcare serial killers are almost always the elderly, disabled or the very young the most vulnerable people in society. But in some of the cases you will read, serial killers such as Charles Cullen, Harold Shipman and Vickie Dawn Jackson also targeted people in the prime of their lives. Being younger and not chronically ill is clearly not immunity to being the target of a serial killer in a healthcare setting.

While writing Angels of Death , I noticed that the pattern of offending with medical serial killers is often alarmingly uniform many of these evil angels worked on a nightshift where they were unsupervised, they had personal problems and mental health issues and there were always one or more red signals that meant they could have been stopped, whether it was a disciplinary issue that was not shared as they moved from job to job, a drug addiction, a criminal conviction or a cloud over their professional practice In a number of cases detailed in this book, many of these murders could have been prevented had there been more rigorous checks and balances in place from the hospital right up to state legislation.

When I set out to write this book, I had heard of the high-profile cases of healthcare serial killers such as Dr Harold Shipman, Britains worst (and possibly one of the worlds worst) serial killers. Shipman is believed to have murdered more than 200 of his patients with overdoses of the narcotic diamorphine. Id also heard of English nurse Beverley Allitt who killed four babies and children in her care with fatal doses of a drug that induced cardiac arrest. Allitt had the characteristics of the rare condition Munchausen syndrome by proxy (inflicting injury on others to gain attention for oneself) and Munchausen syndrome (inflicting injuries or inducing or faking sickness and symptoms on oneself). These conditions are extremely serious personality disorders that can prove fatal, as they did for Allitts tiny victims.

I was also familiar with the case of Roger Dean, the Sydney registered nurse who in 2011 started fires at the nursing home where he worked so that he could thwart an investigation into his theft of drugs from the facility. Deans actions caused the terrifying deaths of 11 of the nursing home residents who were elderly, frail and unable to flee to safety.

However, some of the cases were new to me, like the chilling story of Texas nurse Genene Jones, who is suspected of killing almost 50 babies while working as a nurse. Victims advocates and people involved in the original case are actively trying to stop the Texas baby killer from being released from prison. Jones is eligible for release in 2018 under a mandatory release law in Texas that means prisoners with good behaviour must be freed after serving a percentage of their sentence. In Joness case she will have served just over 34 years of her 99-year sentence for the murder of an infant girl. The loophole, which has now been closed, was intended to reduce prison overcrowding. Now, the families of Joness victims and are trying to find another family whose baby was killed by Jones so they can keep her in jail.

Before researching this book, I had not realised just how many healthcare professionals have been found guilty of murder. Frankly, it is disturbing. It could be argued that healthcare serial killing is the easiest type of murder to commit and get away with for years, or possibly forever. Serial killer nurses and doctors do not have to go looking for their victims they literally have a captive audience from which to choose.

All crime has a terrible impact on the lives of families and loved ones of the victims. However, there was something particularly sinister about the cases featured in this book. I kept thinking of it as casual horror in that the very people who were tasked with caring for the victims had made a decision to instead end their lives, as quickly as it took to give an injection or smother someone who simply could not defend themselves.

Serial murder by healthcare professionals is particularly evil because these offenders have an enormous amount of responsibility and skill that should be used to save lives and comfort people. Instead, they use their position to violate the vulnerabilities of their victims.

It is an unforgivable betrayal of trust.

Emily Webb

Melbourne

Charles Cullen

Satans Son

Love was what Charles Cullen, a nurse in New Jersey, USA, believed could save him from the death wish that had been his companion since he was a child. At just nine years of age, Cullen had made his first suicide attempt by drinking a mixture from a home chemistry set. The attempts to end his life would continue for years until he found another way to channel the self-disgust, low self-esteem and depression that had plagued him for most of his life. In fact, Cullens mental torment and victim mentality belied a rat cunning that saw him prey on some of the most helpless, sick and trusting patients whose families believed they were safe and would be nursed with care and compassion. Little did they know that their loved ones were in grave danger at the hands of Nurse Cullen, who had a compulsion to kill. Cullen was able to hide away by working graveyard shifts in intensive care units (ICUs). The unsociable hours and inability for patients to communicate with him meant that Cullen could murder easily. There was no one to watch him and there was effortless access to his weapon of choice prescription drugs.