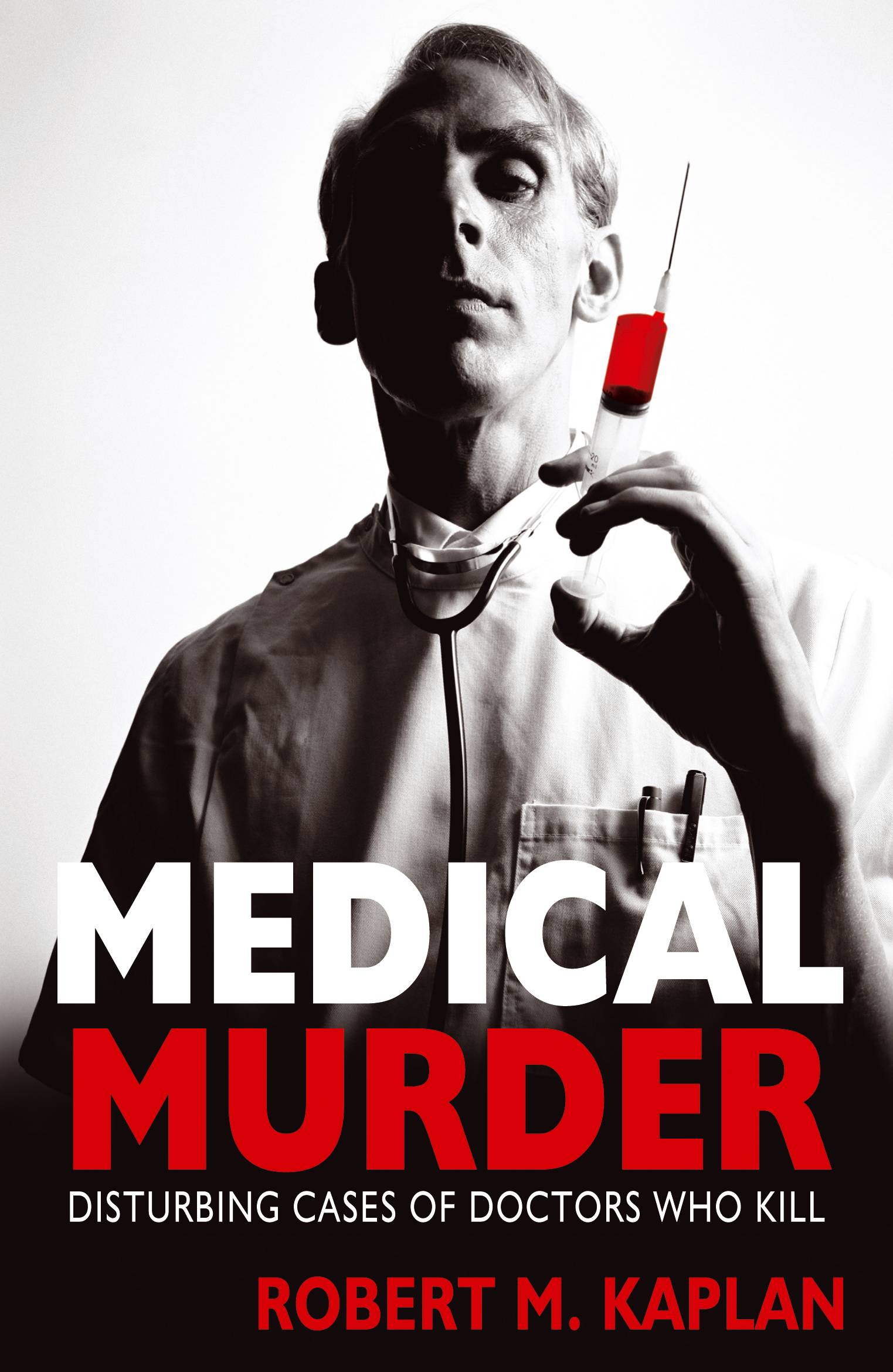

Dr Robert M. Kaplan leads a double life. In his day job he is a forensic psychiatrist, Clinical Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, and associate member of the South African Association of Professional Archaeologists. In his other life, he is a writer, historian and student of the vagaries of human nature. He has written and published on medicine, psychiatry, history and crime; subjects include Dr Radovan Karadzic, Adolf Hitler, James Joyce and Sigmund Freud. His interests include serial killers and medical crime; the origin of modern humans; Jewish life and Talmudic thinking; medical messiahs, moral panic and modern witchhunts.

He has broadcast on ABC Radio, given talks to a range of audiences and published in Australasian Psychiatry , the British Medical Journal , South African Medical Journal , Medical Observer and Scope . He was consultant to Professor Charles van Onselen for his book The Fox and the Flies : The World of Joseph Silver , Racketeer and Psychopath . He regularly goes to South Africa to visit museums, prehistoric diggings and encounter some of the best historians and archaeologists in the world.

Born in Edinburgh, raised in South Africa and living in Australia for several decades, he is waiting for the authorities to deport him. To the small circle of private individuals prepared to admit that they know him, he is regarded as a more than fair cook, a feckless word spinner and obsessive alliterator who keeps unreliable hours and is utterly unable to take anything seriously. He maintains an unfulfilled ambition to complete his autobiography, working title Memoirs of a Marginal Medical Student .

Prologue

In January 2000, world-wide headlines announced that English general practitioner Dr Harold Shipman was found guilty of murdering fifteen of his patients. Before his trial, many had assumed that Shipman was an overzealous doctor doing no more than easing the passing of dying patients. But the evidence showed otherwise; Shipman deliberately murdered not just fifteen, but several hundred patients in the most efficient mechanical and indifferent fashion, making him a hitherto unparalleled medical serial killer.

Shipmans American epigone, aspiring neurosurgeon Dr Michael Swango, spread his net across the US, Zimbabwe and Zambia, leaving a trail of bodies in his wake. Sydney psychiatrist Dr Harry Bailey killed close to a hundred patients with Deep Sleep Therapy, a discredited and dangerous form of treatment. Dr Radovan Karadzic, the psychiatrist who led the Bosnian Genocide, shelled the hospital in Sarajevo where he had worked, killing colleagues and patients.

The phenomenon of medical killing has been largely ignored and there has been no attempt to understand the basis for such extreme behaviour. In this book, I explore clinicide a new termdefined as the death of multiple patients in the course of treatment by a doctor. The study of clinicide raises powerful and disturbing questions: why do doctors deliberately kill their patients, ignore appalling death rates, or use their medical skills to participate in horrendous experiments, torture or genocidal murder in the service of the state?

Medical murders are appalling but unusual crimes. It is a paradox, considering the extraordinary effort, discipline and devotion that it takes to become a doctor when throughout history medicine has been regarded as a sacred calling. While the incidence of medical killing is very low, this is little consolation to the victims or their families.

I have examined clinicide in the context of the history of medicine, forensic psychiatry and sociology. The role of the healer, medicine man or doctor is universal and little, aside from advances in technology, will change this. The motives of doctors are as much an expression of the prevailing culture as scientific progress which, in many cases is suborned by its practitioners for all too-human motives.

I explore medical killers over time, focusing on Harold Shipman, Michael Swango, Harry Bailey, John Bodkin Adams and Radovan Karadzic.

That some doctors become killers says much about human nature, society and the practice of medicine. But it should be remembered that very, very few members of a great profession follow this path. The practice of medicine is an inherently good activity, and it is to the credit of the profession that there are so few killers. I hope this book will make a contribution to keeping it this way.

Dr Robert M. Kaplan

March, 2009

1

The rise and fall of the medical calling

The most incisive words on medical murder were written in 1978 by forensic pathologist Keith Simpson:

Doctors are in a particularly good position to commit murder and escape detection. Their patients, sometimes their own fading wives, more often merely aging nuisances, are in their sole hands. Dangerous drugs and powerful poisons lie in their professional bags or in their surgery. No one is watching or questioning them, and a change in symptoms, a sudden grave turn for the worst or even death is for them alone to interpret.

Doctors, Simpson pointed out, authorise the removal of a dead patient by writing the death certificate. If they take the law into their own hands, it is only likely to emerge through chance, whisperings or rumour, or careless disposal of the body. That medical murder emerges so seldom, considering the number of practitioners, is either a testimony to their moral fibre or the ease with which they can conceal crime.

English psychiatrist Herbert Kinnell rates doctors as the greatest killers among all the professions. Doctors as a group are murderous: they kill family and friends; they kill their patients; and they kill strangers, chiefly for political reasons, by torture, mass murder or genocide.

Medicine has always had an attraction to those interested in power over life and death, status and the acquisition of wealth. The first factor in its appeal to potential killers was the institutionalisation of medicine. Legitimisation put the medical profession in a position of power, authority and status it has ever since been reluctant to cede, a built-in factor attracting a certain kind of psychopath.