ON ILLUSTRATION

First published in 2011 by Oberon Books Ltd

This electronic edition first published in 2012

Oberon Books Ltd.

521 Caledonian Road, London N7 9RH

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7607 3637 / Fax: +44 (0) 20 7607 3629

e-mail: info@oberonbooks.com

www.oberonbooks.com

Copyright Andrzej Klimowski, 2011

Andrzej Klimowski is hereby identified as author of this work in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The author has asserted his moral rights.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or binding or by any means (print, electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

PB ISBN: 978-1-84943-112-5

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84943-280-1

Visit www.oberonbooks.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that youre always first to hear about our new releases.

Introduction

T hese short reflections on illustration will appear fragmented. I have no clear theory or definition of the subject yet I am aware that without it cultural and artistic life would be impoverished. Illustration heightens an artistic experience, both emotionally and intellectually. Often it is our first introduction to culture. It is a form of art that runs closest to everyday life, its presence can be found in the ephemera of the everyday, in newspapers, journals, television, fashion and on the packaging of consumer products.

What follows is an insight into my practice which hopefully helps define the role and status of the illustrator in the creative industries. As a teacher I am often asked to speculate about the future of illustration and of visual communication in general, but I struggle to come up with a clear opinion. I focus on each job as it comes, be it a commission or a self-motivated piece of work. After all, illustration addresses given subject matter, be it literary, journalistic, philosophical or purely commercial. The reader may notice that a few concerns and influences come up more than once during these reflections. Inevitably I have been affected by my mentors, clients, students and specific works of art.

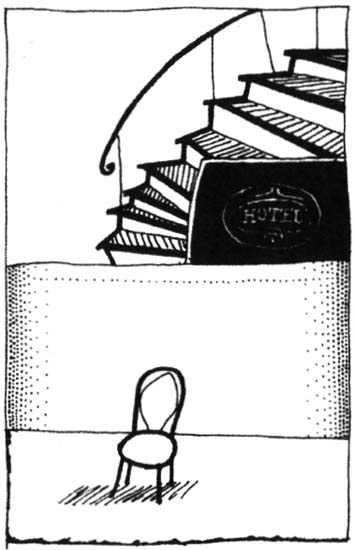

Illustration lies somewhere between graphic design and painting. Its context is graphic design. An illustrators work will find its way on to a newspaper page, into a magazine, a book, a poster, on a webpage or a television screen. It will accompany text, illuminate it, comment on it, punctuate or counterpoint it. Its function can be reflective, provocative or decorative. It enlivens visual communication.

What it shares with painting is the desire for self-expression. It expands the imagination. Prior to the nineteenth century painting was illustration. In Europe it served the Church. A largely illiterate society was able to follow the teachings of the Bible through the spoken word augmented by imagery found in churches and cathedrals. Scenes from the Bible were depicted in frescoes, icons, mosaics and stained glass windows. In the baroque period painting became the instrument of the Counter Reformation. The opulent, often ecstatic imagery was a force that endeavoured to hold the Catholic Church together as it underwent a legitimate criticism from Protestantism which in turn placed emphasis on the word. The interiors of Protestant houses of worship were whitewashed; the focus was on the pulpit, not the altar and ceilings heavily decorated with portentous frescoes and statues.

The emphasis on the visual continued to recede during the Enlightenment. Painting was eventually liberated from its illustrational role through the popularization of print and the invention of photography. Photography was now seen as the most accurate medium for depicting reality. During the Victorian period engravings based on photographic references were the most widely used form of illustration. Popular novels by authors such as Charles Dickens were serialized in weekly magazines; each episode would be accompanied by a large illustration. The golden age of illustration had begun. Artists such as Gustave Dor and Honor Daumier in France and Aubrey Beardsley in England were celebrated. Their work was closely associated with writers and poets such as Oscar Wilde and Charles Baudelaire. Baudelaire himself held the illustrator in greater esteem than the painter. In his essay The Painter of Modern Life he praised the illustrator for being a man of the world, broad-minded and sensitive to the workings of modern life. The artist/painter by contrast, was more limited, tied to his palette and easel, living a secluded, bourgeois existence.

According to Baudelaire, the illustrator was at the centre of contemporary life, recording the behavioural patterns of different social classes, their fashions and gestures, the elegant boulevards and arcades with their shops and the slums of the poor and underprivileged. Baudelaire focused his attention on an illustrator who he referred to as Monsieur G, a man whose work regularly appeared in the leading Parisian magazines and journals. G did not limit his work to illustrating urban life but depicted military campaigns and the Crimean War for The Illustrated London News. Baudelaire admired the humility of this illustrator who rarely signed his work, at best leaving his initials in the corner of some of his compositions.

Even today many illustrators hold on to their anonymity. Often the public are well acquainted with illustrations they see in newspapers, on book covers and posters, but rarely are they able to identify the illustrator. This lies in sharp contrast to the celebrity status of fine artists.

...

Graphic design and illustration are the same as painting.

...

What interests me is form. Wrestling with form. I am not concerned with defining my profession.

...

Its important for me to create my own pictorial lexicon, a new grammar. To have my own formal values, my own language, my own voice.

...

With every new commission comes a new struggle. I wrestle with a problem that has to be worked out according to new criteria. To find an appropriate form for specific subject matter is demanding. With practice much of the work becomes automatic, a reflex action.

...

These thoughts reverberate in my mind; I take them to be my own. In truth they belong to my old professor, Henryk Tomaszewski.

1

Amsterdam

I n April 1991 I persuaded Eye, the international graphic design magazine, to send me to Amsterdam to cover Henryk Tomaszewskis retrospective exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum. I had not seen my old professor for nearly ten years and was eager to catch up with all the news. After I left Warsaw I corresponded with him and received beautifully illustrated Christmas and Easter cards from him, characterized by his wicked sense of humour. During the period of martial law many of his letters were marked by the censors thick black lines cancelling out words and even whole sentences. They introduced a certain drama to Henryks idiosyncratic handwriting.

Next page