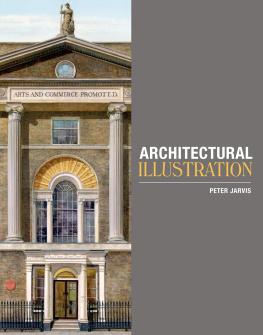

ARCHITECTURAL

ILLUSTRATION

ARCHITECTURAL

ILLUSTRATION

PETER JARVIS

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

Peter Jarvis 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 404 9

Front cover: The RSA building in John Adam Street is the home of The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. It was designed by the Adam brothers and completed in 1774 as part of their innovative Adelphi scheme. Several photographs were used as primary reference to piece together this view of the faade, which could not be seen in reality due to the narrow street. Watercolour over pencil on 90lb Canson Montval Aquarelle NOT stretched watercolour paper at 500 360mm.

Frontispiece: Southamptons Bargate was built around 1180 and is constructed of stone and flint. It was the gateway to the walled city of Southampton and formed part of its fortifications. The dark washes applied to the underside of the archway establish the tonal range of the building and contrast against the view beyond. The figures help to give scale. Watercolour over pencil on 90lb Canson Montval Aquarelle NOT stretched watercolour paper at 350 430mm.

Contents

Introduction

A dictionary definition of the word illustration is: a picture, design, diagram, etc. used to decorate or explain something. This book is about the illustration of buildings and the built environment and how buildings are seen in context. Its not an instruction book on the use of digital methods, or any other medium, but it does cover some basics on a range of applications. It examines the subject primarily from the authors standpoint as a traditional architectural illustrator, but also looks at the illustrators role in broad terms and how architectural design is presented in the public domain. It contains worked examples and step-by-steps, mainly hand-drawn by the author, in order to explain to the novice the fundamentals of the subject. Selected case studies and artists profiles are also included for interest to the more advanced practitioner.

Bishopsgate Institute was designed by Charles Harrison Townsend and opened in 1895 as a centre for culture and learning. This illustration shows the faade of the building as seen from the opposite side of Bishopsgate, but the naturally occurring vertical convergence has been corrected in Photoshop. Designed in the fashionable styles of the Arts and Crafts movement and the Art Nouveau style, this building has all the elegance of this period with filigree stonework and decorative twin roof turrets. Watercolour over pencil on 90lb Canson Montval Aquarelle NOT stretched watercolour paper at 580 320mm. (Courtesy of Luke Johnson.)

These days many illustrators work by combining traditional skills with computer skills, but its the role of drawing that remains the most important component in providing the foundation to a successful outcome. Drawing is about looking and observation, but its also about enquiry and investigation. Through observation one learns about the nature of a subject; how it works or what materials it is made from. The act of drawing on location, done over an hour or so in a particular place, will enhance other forms of studio-based applications. With regular practice, drawing and sketching skills help to improve an illustrators ability to create convincing and credible illustrations. Technical problems are often easier to solve through drawing and can be communicated without the hindrance of the written word. Many architects start out with freehand concept drawing as a means to exploring initial ideas. Such drawings can be referred to as the outcome of self-commune: engaging in a dialogue with oneself. There are many role-models to look to in this respect: the great architect Ted Cullinan is a master of the sketch and has produced many draw and talk videos, and Sir Norman Foster is an enthusiastic advocate of this type of drawing. The late Hugh Casson famously sketched during his travels and published several books of his work done whilst visiting major British cities. More often than not, the role of the architectural illustrator will move back and forth from visualization to representation; from prediction to documentation, all of which can be described as illustration.

Approaches to drawing can be far-ranging and diverse in purpose and outcome. As a radical visionary, the late Zaha Hadid produced many drawings and paintings in which she explored the limits of architectural form. Much of this work was never realized in built-form but represented the potential of structural possibilities. She used perspective to communicate the dynamics of architecture and in doing so created dramatic results if, at times, somewhat inaccessible to the general public. lvaro Siza, the great Portuguese architect, spoke about the different purposes of drawings: to generate ideas; to develop them; to communicate; or for simple pleasure. Many architects still talk about the pleasure of drawing and sketching as a way of exploring shape and form in design and this is still considered to be important alongside digital methods.

In architectural illustration it is crucial to have a knowledge of building materials and methods of construction. This can be very broad depending on the type and design of a building. Vernacular buildings can date from medieval times and rely on indigenous materials in their construction whereas modern city blocks are made from concrete, steel and glass. Familiarity with building terminology can help to avoid any misunderstandings between the illustrator and client; there is a glossary of terms at the back of this book. Many illustrators specialize in particular building types, often relating their style and method to its appropriate representation: a medieval hall house rendered as a computer generated image (CGI) might not lend itself to the medium as well as the use of traditional pen and ink or watercolour. The important skill here is in maintaining the consistency of style and technique within the illustration.

Photographic skills are also important and acquiring these has been simplified with the advent of digital technology. Many projects require the illustrator to superimpose proposed buildings into photographs of existing urban and natural landscapes. This process is often enhanced by using on-line maps and street views that have now become standard tools in the illustrators toolbox.

The term architectural illustration is a relatively modern one and has its roots in the topographical tradition of watercolour painting occurring at the start of the eighteenth century. Prior to this time early topographical drawings were often the work of surveyors and mapmakers who were familiar with the conventions of architectural drawing and perspective. During the late seventeenth century wealthy landowners would commission aerial views of their country homes from talented draughtsmen and artists. The topographical style was introduced to England in the drawings of Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar (16071677) and taken up by two Dutch draughtsmen, Jan Kip and Leonard Knyff, who produced many topographical views of British country houses and gardens in the form of engravings.

Next page