Botanical Illustration for Beginners

A Step-by-Step Guide

Botanical Illustration for Beginners

A Step-by-Step Guide

Meriel Thurstan

Rosie Martin

First published as Hardback and eBook in 2015 by Batsford

an imprint of Pavilion Books Company Limited

1 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HD

www.pavilionbooks.com

Copyright Batsford, 2015

Text copyright Rosie Martin and Meriel Thurstan, 2015

Illustrations the named

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

eISBN 978-1-849943-07-9

This book can be ordered direct from the publisher at the website:

www.pavilionbooks.com, or try your local bookshop.

batsford_books on Twitter

batsfordbooks on Facebook

BatsfordBooks on Pinterest

Distributed in the United States and Canada by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

1166 Avenue of the Americas, 17th floor, New York, NY 10036

Authors Note: There is often confusion about petals, tepals and sepals. It may not please purist botanists but, for simplicity, if something looks like a petal, that is what we have called it.

Contents

This bisection of a tulip captures its exotic colours as well as its structure.

Introduction

Learning botanical illustration from scratch can be a daunting prospect, so we have tried to simplify matters. Together with examples and explanations, we have set out step-by-step exercises for you to follow, with notes on how to tackle each project. Most are quite simple; others are moderately easy and a few are more challenging.

This book will give you basic and vital information on drawing, colour recognition and mixing, how to lay watercolour washes, understanding and applying watercolour, coloured-pencil techniques, and how to superimpose one colour over another for depth and vibrancy. These are the building blocks of botanical painting.

We also discuss aspects of botanical illustration that you may find more demanding: pattern and texture, composition, complex forms, painting white flowers (without using white paint) and how to paint black flowers and berries.

As botanical illustration can be enjoyed from both an aesthetic and scientific perspective, there is also information on botany and the accepted use of Latin when naming plants.

With time and practice, you should become a competent and proficient artist, able to tackle any botanical subject with confidence. For those with some experience already, remember that however successful you may become, you never cease to learn.

Rosie and Meriel

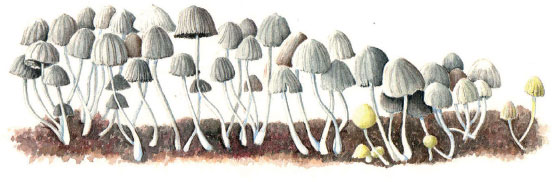

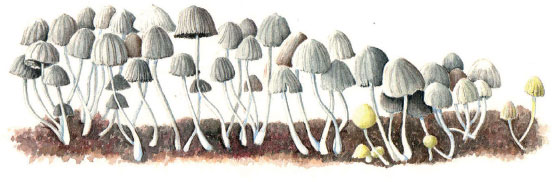

The trooping crumble cap fungus, or fairies bonnets (Coprinus disseminatus syn. Psathyrella disseminata) turns into a viscous black liquid after a few hours, so has to be painted quickly.

Early botanical art

The earliest known depictions of indigenous plants were carved into rock in c.1450 BC to adorn the walls of the Great Temple of Tuthmosis III at Karnak, Egypt. Of the 275 plants shown, not all are identifiable, but they are a timeless record of all plants that grow in Gods Land, which were found when his majesty proceeded to subdue all the countries , as the inscription declares.

The Middle Ages

Medieval monks drew on vellum or parchment using a goose feather quill and ink made out of oak galls. Provided that the artwork was kept safe from predatory bugs and mildew, it survived to inform and give pleasure to many future generations.

Once the printing press had been invented in the mid-fifteenth century, artwork was available to many more people; but once again, these prints had to be suitably preserved in dry, shaded conditions if they were to last for any length of time.

The Vienna Dioscurides is an early 6th century illuminated manuscript of De Materia Medica, the Greek Herbal of Dioscorides. This page from the antique scientific text shows the earliest representation of the Orange Carrot, at the time considered a medicinal plant.

Seventeenth century onwards

Artists who used oil-based paints on canvas, like the Dutch flower painters of the seventeenth century, ensured that their work would survive for centuries, if not forever.

Now, in the twenty-first century, we benefit from the expertise of generations of artists and scientists, and can make sure that we have the best possible materials to hand for our work.

The seventeenth-century painting Still Life of Flowers by Dutch artist Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606-84).

Materials and equipment

Naturally, todays botanical artists want their work to last, so choice of materials is an important consideration. A workman is only as good as his tools, and poor tools will make for substandard work. It can be tempting to economize by buying low-quality paint, paper and brushes, but your work will suffer, so buy the finest that you can afford.

By mixing your own colours from a limited palette, you can create all the many colours found in nature.

Watercolour paints

Research on the manufacture of watercolour paints and their durability has really taken off in the last few decades. Some colours are known to be fugitive, but modern manufacturers colour charts have notes on the lightfastness of each paint, so we can make properly informed decisions.

Initially, keep to a limited , but be sure to buy artists-quality paints. They are a bit more expensive than the students-quality range, but they last longer, the colours are better because they contain more pigment and they are worth every penny.

Watercolour paints come in pans, half pans or tubes. If you opt for pans or half pans, take an empty paintbox and fill it with your choice of colours. If you use tubes, squeeze a small amount on to the palette. If you dont use it all, allow it to dry for next time. It is easily reconstituted with water. Tubes can sometimes be difficult to open. Hold the cap in hot water for a few seconds to loosen.