Title Page

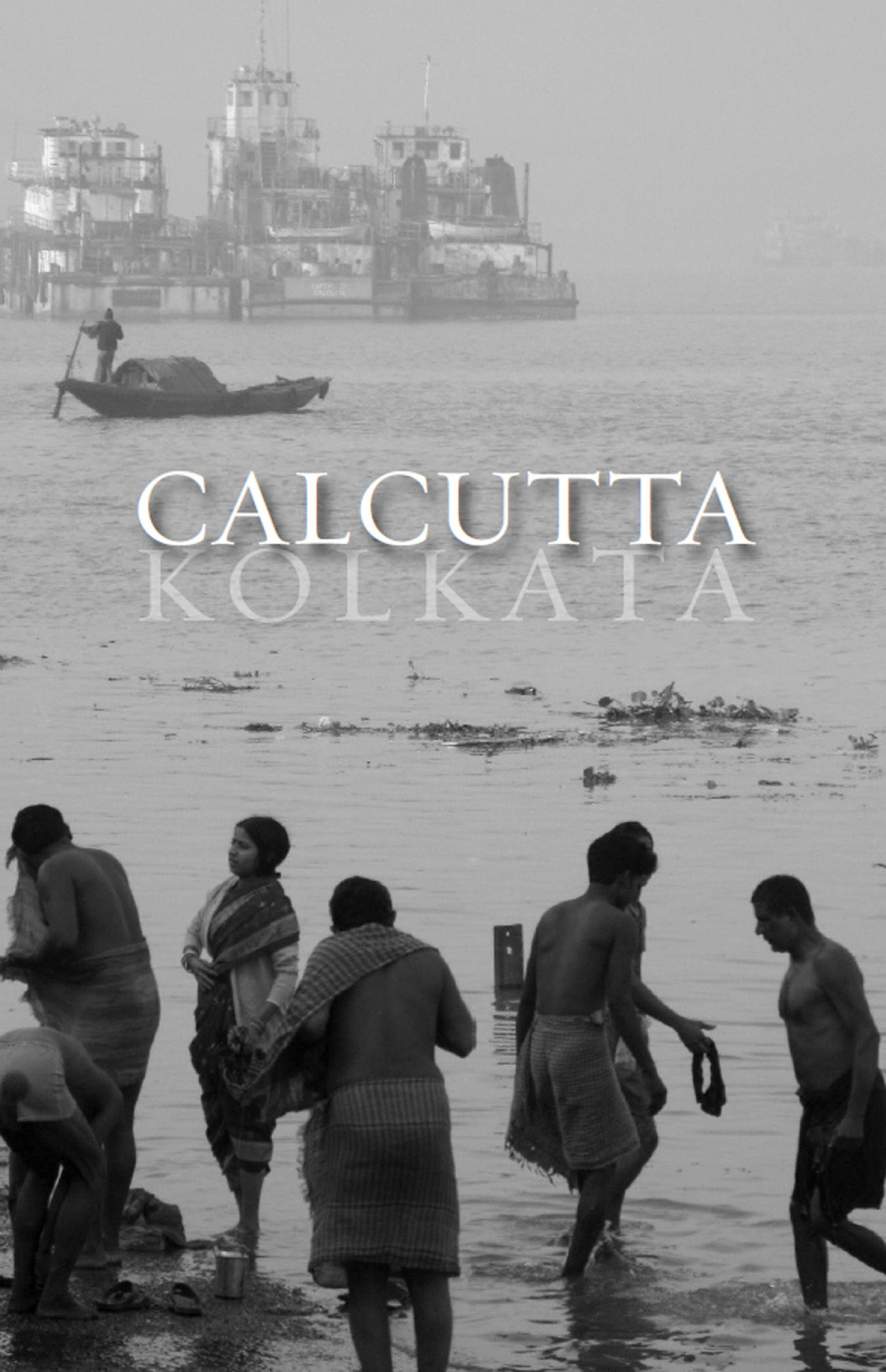

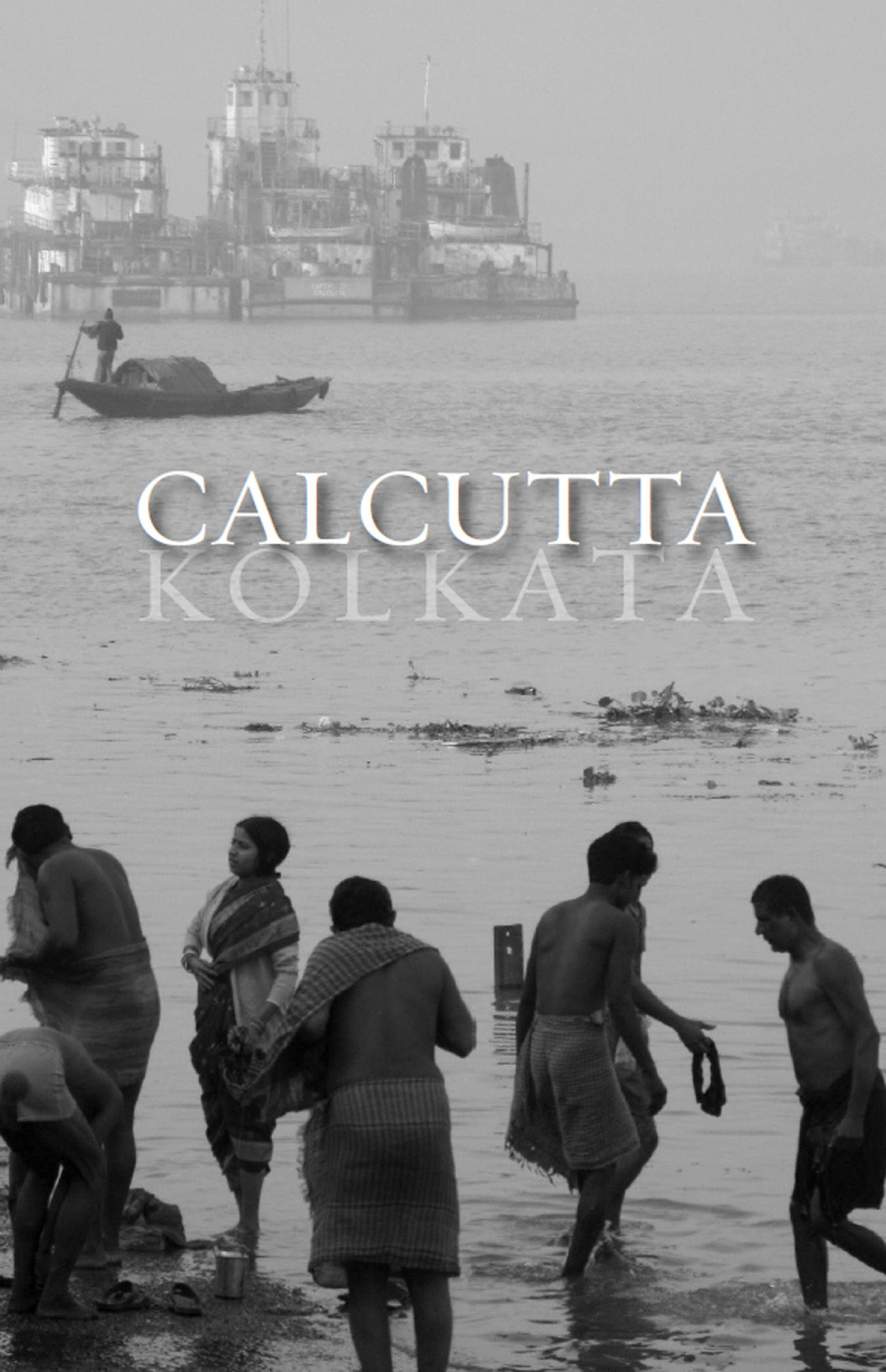

CALCUTTA

A cultural and literary history

by

Krishna Dutta

Publisher Information

First published in 2003 by

Signal Books Limited

36 Minster Road

Oxford OX4 1LY

www.signalbooks.co.uk

Digital Edition converted and distributed in 2011 by

Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

Krishna Dutta, 2003

Foreword Anita Desai, 2002

Text updated in 2009

The right of Krishna Dutta to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. The whole of this work, including all text and illustrations, is protected by copyright. No parts of this work may be loaded, stored, manipulated, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information, storage and retrieval system without prior written permission from the publisher, on behalf of the copyright owner.

Drawings by Wendy Skinner Smith

Cover Design: Baseline Arts

Production: Devdan Sen

Cover Images: courtesy Andrew Robinson; Chandra Prasad / Link; Mark Henley / Panos

Frontispiece photo: Devdan Sen

Dedication

for Andrew

Foreword

When one asks oneself if Calcutta can be called a great city, is one merely asking if it is historic, important, wealthy, grand and imposing? I think another, less denable quality is called for, the quality of myth, and that a great city is one that possesses a reality that verges on the mythical. A book that portrayed the city would be insufficient if it presented only details of its history, climate, architecture and civic life; it would need to go beyond and convey the indenable and non-substantial that make the city even greater in the mind than it is on the ground.

I do believe that Calcutta possesses such a quality because I have seen how profoundly it has affected anyone who has lived in it (and I say lived with reason, not merely visited). I did not set eyes on it myself till I was twenty years old when my father died, our house in Old Delhi was given up and the family moved to Bengal where my brother and sisters had all found employment. Yet it had been present in my life in the form of my father, a Bengali albeit not from Calcutta, for whom the city had always been a destination. He grew up in the countryside of East Bengal, spoke to us of the luminescent green of the rice elds, the riverine life of the people, and the sh and coconuts and rice of his cuisine, the nest in the world, he gave us to understand. I would see his eyes come to life and glow if he heard a snatch of baul music from his land, and I remember the expression on his face as of one who had seen a vision, when we went together to a matinee show of Satyajit Rays rst lm, Pather Panchali . Sometimes a tangible piece of that world came our way in the form of an earthen pot of date palm syrup, or a box of Bengali sweets, the soft milky sandesh , each shaped like a conch shell and packed in rice for freshness. These spoke to us of another culture, a more subtle one. A visitor from Calcutta, on opening a suitcase to unpack, would release a particular odour into the air - damp, mouldy, deltaic, even swampy - that was totally alien to our own arid surroundings. It was as if a large, dark moth had blundered into the crackling dry air of the north. This Calcutta has been most elegantly evoked in Nirad C. Chaudhuris chapter on the city in his Autobiography of an Unknown Indian . In it he exactly replicated my fathers experience of going as a country boy from East Bengal to study in the great second city of the British empire. It is a piece of prose I can read and reread with unfailing pleasure: that line about the feathery and shot effect of the Calcutta sky and what lay beneath it as a crowd of misbehaved and naughty children showing their tongues and behinds to a mother with the face of Michelangelos Night!

Trying now to retrieve my impressions on rst seeing Calcutta as that newly graduated twenty-year old with a vague sense of launching upon a literary career, I remember that my rst reaction was that although I came from the capital of India, Calcutta was the rst true metropolis I had seen. Delhi in the 1950s, even New Delhi, was really nothing more than a handful of villages clustering together on the sand and dust of the northern plain. Calcutta, by contrast, seemed to pulse with a sense of purpose, a condence in its raison dtre . The reason may have been taken away when the capital moved to Delhi but a tradition had been established and habits formed. One saw it in the condent ow of traffic up Chowringhee, in the orderly variety of the markets. Here was no compromise between city and suburb; here was city. How wonderful, I thought, to have piped gas supplied by the city, so a ame leapt up at the turn of a knob! In Delhi we might as well have been camping in the desert, the way we had to construct our lives, but here the city constructed our life for us, making us citydwellers, not junglees . What was more, in Delhi my attempt at breaking into journalism or publishing had been dismissed with scorn whereas in Calcutta I quickly became a member of a Writers Workshop held regularly on Sunday mornings where everything I wrote was considered with attering seriousness. The city had a sophistication about it, I thought, to be found in the delicious sandesh from Gangulys as well as the pastries from Flurys, and the immaculately starched muslins worn by Bengalis. Not to speak of the night-long concerts of classical music that only broke up at dawn, and the lm club where I rst saw the lms of Eisenstein and Bergman.

To counterbalance all this urbanity and sophistication, there were the fervent rites and rituals of worship of the goddess Kali, at times in her ferocious and at other times her benign aspect as the mother goddess, Durga. Also the elaborate rituals of lesser ceremonies like those associated with marriage - all in the heat and humidity, to the lowing of conch shells and wreathed in the heady fragrance of tuberoses. In fact, there was a certain murkiness about the city, too. I thought it had to do with the gas lamps along the shadowy streets, the tides that rose and fell on the inland river, the reection of tall houses in the still, dark ponds that took the place of city parks and squares. But it was much more than that: a covert danger and implicit violence that warned one that the various currents of city life swirled around in it, restless and unresolved - the past and the present, the rich and the poor, the literate and artistic and the illiterate and hungry. They contradicted each other at every turn: the smog that smothered the city could be of winter mist or of factory smoke, the monsoon rains could be cooling and refreshing or intemperate and disease-ridden, the colour red could be festive and celebratory or a signal of danger and violence... In his reminiscences of his childhood in the city, Rabindranath Tagore wrote: Something undreamt of was lurking everywhere, and every day the uppermost question was: where, oh where would I come across it?

When I left Calcutta in 1962, I carried with me a sense that I had not discovered its secret, it had eluded me, and this led me to start reading its literature. The very best of writing gives voice to the essential spirit of a place; think of the writers of the deep South of the United States, those from the coasts and forests of Latin America, or from the vastness of the Russian steppe. Bengal, too, has its voice - and one hears it in the poetry of Tagore, the prose of Bibhuti Bhushan Banerjee, as well as the music produced by the wandering minstrel, the baul singer, and encounters it in the lms of Satyajit Ray - all possessed by the mystery, the mystique of Bengal, with Calcutta at his heart.

Next page