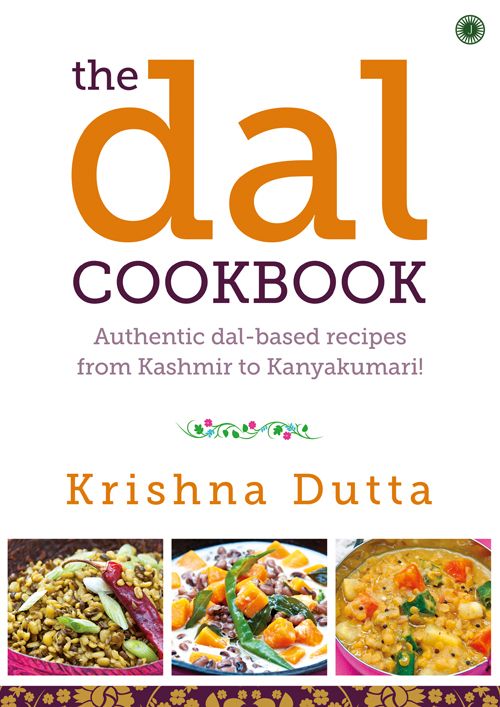

Published by Jaico Publishing House

A-2 Jash Chambers, 7-A Sir Phirozshah Mehta Road

Fort, Mumbai - 400 001

www.jaicobooks.com

Text copyright Krishna Dutta 2013

Copyright this edition Grub Street 2013

To be sold only in India, Bangladesh, Bhutan,

Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

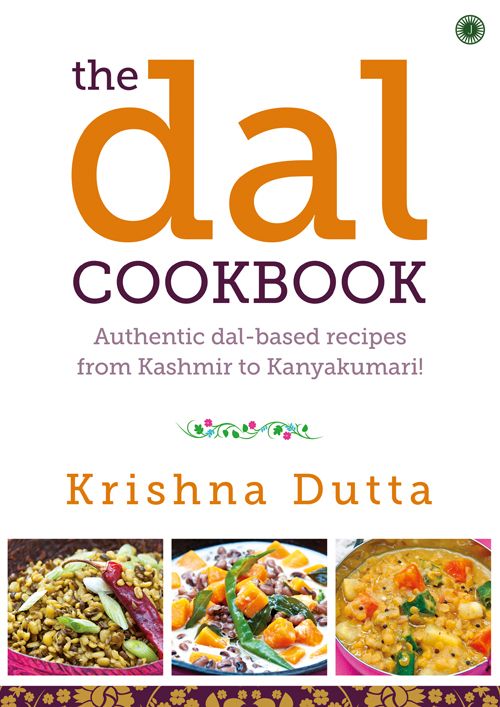

Design Sarah Driver

Photography Michelle Garrett

Food styling Jayne Cross

Published in arrangement with

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close, London SW11 6SS

email:

web: www.grubstreet.co.uk

THE DAL COOKBOOK

ISBN 978-81-8495-940-6

First Jaico Impression: 2016

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Dedication

For my darling grandson Arun, who has been

nourished by my dal since he started life in his mummys tummy

Contents

- Recipes

Northern Indian

INTRODUCTION

When I came to the UK as a young student from India in the late 1960s, British cuisine had a relatively poor reputation compared with that of other European countries such as France or Italy. What I ate then was often dull to say the least. Vegetables lacked variety, the range of spices was limited, and recipes in circulation were uninspiringly conventional. For me, food those days was merely fuel. I ate to live and to work.

Then one day walking down Drummond Street near University College London, I discovered a couple of small and shabby ethnic grocery shops selling exotic but well out of date vegetables like aubergine, mooli, stem of ginger and red chillies. I felt curious and walked in to find varieties of Indian dried lentils and pulses in packets on shelves. Promptly I bought a quantity of the ubiquitous red lentils and a few spices, a shrivelled piece of ginger and some dried chillies, went home and cooked them in the only pan I had on a small hob in our tiny bedsit with no fire escape. I can still recall the floating spicy aroma it generated and the thrill I felt savouring the dish with my husband and friends who happened to call in that day.

I did not soak the lentils before cooking, just threw in the spices I had bought and boiled them together. Nevertheless what I cooked instantly rejuvenated my Indian taste buds. I craved more. I also rediscovered the power of this simple staple dish I grew up with. In an instant I was liberated from the dreariness of the 60s British diet.

Later I began experimenting with other varieties available in those shops with varying degrees of culinary success. At my request my mother sent me some of her recipes to try. I could not always get the spices she mentioned, so I began to recreate dal dishes with what was readily available. For example I garnished red lentils with fine fennel leaves from the back garden instead of coriander leaves as it was not readily available then and I dry-roasted split yellow moong lentils in the oven as the sun-dried variety was unobtainable.

As I continued to live and work in London cooking and serving lentils to family and friends, the dish of dal became a part of my set menu for suppers over thirty years. In fact it became my signature dish. During the 1980s and 90s my speciality in dal cooking earned some approval among British friends who tested my preparations and encouraged me to write down these recipes.

This prompted me to collect other Indian dal recipes and try them out in my kitchen. Soon I came to realise that dal is truly a pan-Indian dish consumed by rich and poor alike. I was most impressed by the multiple ways of cooking dal, the wide-ranging seasonings used and the diverse supplements to serve with it. I began to grasp how over the centuries Indian cooks became innovative. With locally available ingredients they dished out dal to satisfy a regional palate. In the process they also invented new dishes using dal lentils such as kedgeree (khichuri a risotto made with dal), dosas (pancakes made with dal flour), vadas (dal fritters), dhokla (baked savoury dal cakes), poppadums (dal crackers) and pakoras (fried snacks dipped in dal batter). The more recipes I garnered the more I felt the desire to share my findings with the food enthusiasts of my adopted country.

The nutritional content of this humble food also intrigued me. Dal is rich in protein and has practically no sugar and is known as poor mans meat in India. Doctors now recommend it in a diet for diabetics. Indeed dal is so wholesome that it is one of the few dishes you could subsist on almost entirely and still be in good health.

Over the last two decades British food culture has been enriched by the impact of ethnic cuisine. Myriad spices, vegetables, lentils, pulses, beans and other ingredients are now widely available in restaurants and supermarkets. The word dal has now rightfully entered the British cookery lexicon. The time seems right to transfer my working notes on dal into a proper book for British gastronomes.

Krishna Dutta, 2013

WHAT IS DAL?

Etymologically the word has a Sanskrit origin meaning to split. Applied to edible dried pulses, lentils and beans it came to suggest peas or beans, which have been stripped of their outer hulls and split. Later the word also came to denote the whole kernel with or without casing as well as the cooked dish.

In ancient Indian kitchens the word was transformed into a metonym and contemporary Indian restaurants often denote it as dal soup in the menu. However like most Anglo-Indian vocabulary the English spelling of this word is whimsical. The common variations are dahl, daal and dhal. Dal is more phonetic.

The Original Indian Staple

Archaeologists maintain that humans have been consuming lentils, peas and beans since the dawn of civilisation. A recent excavation on the border between Thailand and Burma carbon dated peas and pulses at around 9750BC. Crops have been cultivated in Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa since antiquity.

Buddhism and Jainism, founded in India around 5th century BC, promoted vegetarianism, which prompted the search for protein other than meat.

Dal is mentioned in a Buddhist manuscript dated around the 10th century. One of the best records of Hindu courtly cuisine from the Chalukyan King Somesvara III (11261138) cites dal as an element of a healthy diet. Ayurveda the traditional Indian science of holistic wellbeing highly recommends dal as a wholesome food and prescribes recipes.

Cheap to produce, highly nutritional, easy for long storage and able to be cooked with a basic pot on an open fire, this food has been providing quality nourishment to millions of impoverished Indians for millennia. The rich too customised its versatility to create sumptuous dishes fit for the Maharajas. Even the itinerant colonial officers on duty in distant parts of the subcontinents supped on kedgeree cooked by their Indian orderlies under open skies. Later the British expatriates imported this basic dish to Europe in its Anglo-Indian incarnation adding fish to the original vegetarian recipe. Supermarkets now mass-produce kedgeree as ready-made meals.

Though the affluent carnivorous communities in the west mostly neglected legumes except for a brief period of attention during the two world wars, British nutritionists and food connoisseurs have finally caught on to their value. More grocers, supermarkets and restaurants these days offer popular varieties of dal.

Next page