Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

FOLKS FROM DIXIE BY PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR IS THE FIRST BOOK OF short fiction by one of American literatures earliest great black authors. In this 1898 work, Dunbar grapples with acceptance, audience, and artistic vision, while utilizing the plantation tradition as a vehicle to speak, in the main, to white Americans. Folks from Dixie, more than anything else, is a book about race consciousness: Dunbar examines black and white roles and attempts to show his largely white audience that blacks are both human and African. On the surface, the book is a series of stories about contented, loyal blacks and peaceful race relations; however within the collection, there is a subtle yet consistent examination of the mors of race relations beneath the surface of the plantation myth.

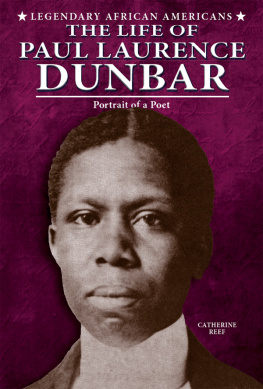

The son of former slaves, who divorced when he was young, Paul Laurence Dunbar was born June 27, 1872, in Dayton, Ohio. His father, Joshua, had escaped from slavery in Kentucky and served in the Massachusetts 55th Regiment during the Civil War. He later worked as a laborer and died in 1884. Dunbars mother, Matilda, was a domestic. She nurtured her sons love of literature and told him stories about plantation life, which served as literary inspirations for his poems and stories. Dunbar attended grade school and Central High School in Dayton and was editor of the High School Times and president of the schools literary society. In 1888, he published his first poem, Our Martyred Soldiers, and in 1890, he edited and published a short-lived newspaper, the Dayton Tattler, with the aid of Orville and Wilbur Wright, high school friends. Upon graduation, Dunbar was unable to find suitable employment and thus began working as an elevator operator; while employed as such he continued to contribute poems and stories to local newspapers. More significant exposure came in 1893 when Dunbar published his privately printed volume of poetry, Oak and Ivy. In 1895, he privately published Majors and Minors, his second volume of poetry, with the help of Dr. H. A. Tobey and Mr. Thatcher, white patrons who had wanted to send Dunbar to Harvard. It was this volume that the esteemed critic William Dean Howells famously reviewed. Howells praised the dialect verse (minors) but dismissed the poems written in standard English (majors), a verdict that haunted Dunbar and with which he grappled his entire career. This review marked the beginning of Dunbars fame as a writer, and it led to the publication of Lyrics of Lowly Life, by Dodd, Mead and allowed Dunbar to begin to tour nationally and internationally with his work. On March 6, 1898, he married Alice Ruth Moore, a teacher and writer, against her familys objections, due to Dunbars color and caste. Their marriage was turbulent, and they separately permanently in 1902. Dunbar died in Dayton on February 9, 1906, of depression and tuberculosis. A prolific writer, Dunbar ultimately published twelve books of poetry, four books of stories and plays, and four novels.

At one point in his life, Paul Dunbar writes to his friend, Dr. H. A. Tobey, suggesting that it is his all-absorbing desire to be a worthy singer of the songs of God and Nature. To be able to interpret my own people through song and story, and to prove to the many that after all we are more human than African. In this regard, Folks from Dixie is quintessential Dunbar, a sensitive, although conciliatory portrayal of black life, which offers subtle or even understated protest, but protest nonetheless.

Contributing to the sense of artistic compromise within this collection is Dunbars use of the plantation tradition formula for a number of the stories. The plantation tradition is a genre, popularized during the late nineteenth century through the works of Thomas Nelson Page (1853-1922) and other white male writers that offers a sentimental view of the antebellum South. Within this view, the white slaveholders are beneficent and genteel and the slaves are contented, well behaved, and exceedingly loyal. Replete with racial stereotypes, stories within the genre suggested that the plantation life was a golden age, substituting nostalgia and racial stereotype for realistic portrayals of southern life.

Some of the material for Folks from Dixie is based upon Dunbars recollection of stories told to him by his parents. The ex-slaves living in Howard Town in Washington, DC, also provided material for the stories to Dunbar. Several of the stories had already been published: Anner Lizers Stumblin Block in the Independent (May 1895), The Deliberation of Mr. Dunkin in Cosmopolitan (April 1898), and A Family Feud in Outlook (April 1898). Of the twelve stories within the collection, five were based in the antebellum period and seven are post-bellum. The publishers chose E. W. Kemble to illustrate Folks from Dixie; one may interpret Dunbars acceptance of Kemble as illustrator as yet one more example of accommodation on the part of Dunbar. Kembles depictions of blacks, which Dunbar biographer Benjamin Brawley labels grotesque illustrations, are classically stereotypical, with exaggerated eyes, lips, and expressions. This Barnes & Noble edition therefore does not include the illustrations. Yet, in spite of Dunbars apparent conciliation, the writer counters stereotype and offers a veiled protest through the use of symbolism, irony, and humor, as well as through the placement of the stories within the collection. As is the case with a later collection of stories, The Strengthen of Gideon, the order of the stories within Folks from Dixie is central to any discussion of the collection as a whole. The first few stories in the collection are, on the surface, more stereotypical in plot and characterization, while the later pieces are more overtly political.

Anner Lizers Stumblin Block, the initial story in the collection, is a piece about slave religion and a love relationship. (The story was probably written during Paul Laurence Dunbars courtship of Alice.) Clearly, a story about two lovers would have been an ideal one with which to begin a collection of sentimental stories about days gone by in the South. However, it is also a story about the institution of slavery and the way in which it affected black love, black family, and black lives. On the surface, the piece offers an idyllic, romantic depiction of plantation life:

It was winter. The gray old mansion of Mr. Robert Selfridge, of Fayette County, Ky., was wrapped in its usual mantle of winter somberness, and the ample plantation stretching in every direction thereabout was one level plain of unflecked whiteness. At a distance from the house the cabins of negroes stretched away in a long, broken black line that stood out in bold relief against the extreme whiteness of their surroundings.

On the surface, both the title and the opening paragraph suggest that this is a story about plantation life, Negro love, and the stumblin block to that love. However, a real, yet almost imperceptible stumbling block is symbolically suggested by the words, unflecked whiteness and extreme whiteness to describe the plantation in winter. These words, when contrasted with the broken black line signify not only the plantation and its master, but also the system of chattel of this or any plantation. Ostensibly, this love story, regarding Anner Lizer and Sam has to do with Anner Lizers inability to get religion at a slave revival, due to Sam. Sam wont definitively commit to Anner Lizer and so she is unable to get religion at the altar prayer service of the black church on the plantation. After many days of unsuccessfully tarrying and praying for the Spirit, Anner Lizer, consults both the Lord and Uncle Eben, the wise old slave who offers her religious advice. At some point Anner Lizer is taken by the Spirit to the forest, and there she finds her lover, chopping wood, and she confronts him regarding his intention, if he wishes to marry her or another slave belle. Once Sam replies that he does, indeed, wish to marry her, he adds, you know I wants to may you jes ez soon ez Mas Robll let me. On the surface, Sam was her stumblin block, yet, in actuality, within the story, Dunbar offers an ever-so-veiled critique of the institution of slavery which created a long, black broken line of people who can only marry when Mas Robll let [them].