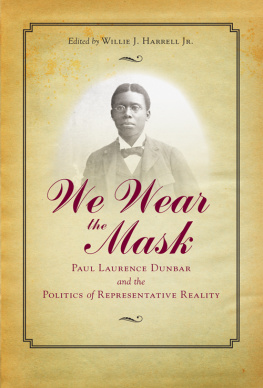

Paul Laurence Dunbars Inspirational Poems

I know why the caged bird sings, wrote Paul Laurence Dunbar in Sympathy, one of his best-loved poems. Born in 1872 to former slaves, Dunbar touched the nation with poetry that portrayed the sorrows and the joys of African-American life. He was a social critic at a time when few people spoke out about race relations. In poems, stories, and newspaper articles, Dunbar expressed his outrage at the unfair treatment of African Americans.

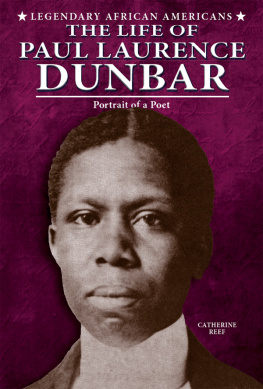

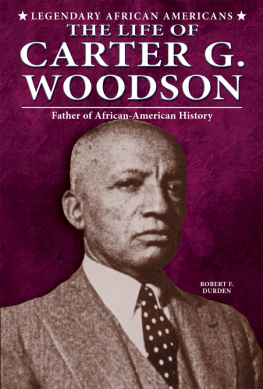

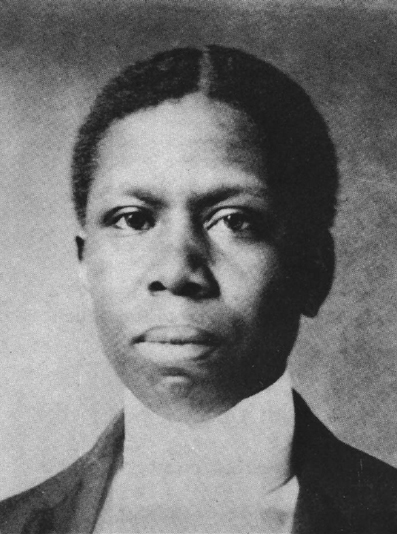

In The Life of Paul Laurence Dunbar: Portrait of a Poet, author Catherine Reef paints a rich and memorable portrait of the first African American to earn his living as a writer. Dunbars work spoke directly to the hearts of his readers, and his legacy inspired the generations of African-American poets that followed.

Excerptsand numerous quotes enliven the text.

School Library Journal

Well-rounded, clearly written

The Horn Book Guide

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Catherine Reef has written dozens of books for children and adults. She enjoys learning about people who made important contributions to American culture.

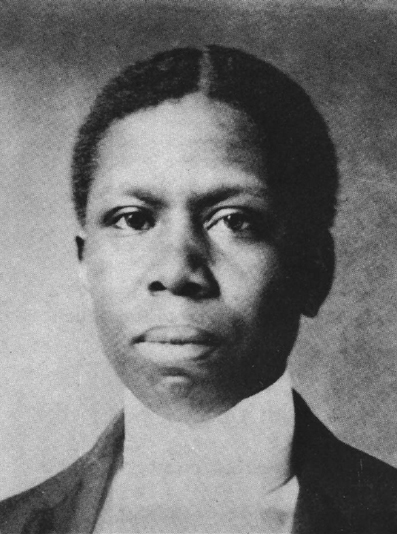

Image Credit: Courtesy of Ohio Historical Society/Reproduced by the Dictionary of American Portraits, published by Dover Publications, Inc. in 1967

Paul Laurence Dunbar touched the all types of Americans with poetry that portrayed the sorrows and joys of African-American life.

The man at the door had a wrinkled face and a body bent from years of hard labor. His worn clothing made him look out of place in this stylish neighborhood of Washington, D.C. For much of his life, the old man had worked as a slave on an Alabama plantation. It was now 1898, and he had been a free citizen for thirty-three years. But he never would forget his years of enslavement.

Paul Laurence Dunbar invited the man in, asked him to sit down, and offered him something to drink. Dunbars gentle manners made the man feel right at home. Dunbar appeared to have little in common with his guest. Dunbar was in his mid-twenties, expensively dressed, slim, and agile. He was also quite famous. In the closing years of the nineteenth century, he was one of Americas best-known writers. He was the first African American to earn his living writing poetry, novels, magazine articles, and essays.

Paul Dunbars own parents had been born into slavery, though. He felt a kinship with people like this man, the former slaves who lived in Howard Town, a poor section of the city. He liked to listen as they talked about the past, even though they might bring up painful memories of life before the Civil War. Dunbar was writing a collection of stories titled Folks from Dixie based on their recollections.

On this day, the visitor related a disturbing tale about something that happened after slavery had ended. He told about the lynching of his nephew, a young man wrongly accused of a crime. Night riderslocal whites acting under cover of darknesshad snatched the youth from his jail cell and carried him off. Denying him a trial, they had hanged him from a mammoth oak tree. From that time forward, while most of the tree flourished, the branch from which his nephew had hung dried up and died. People whispered that the nephews ghost haunted the tree, the old man said.

The story touched Dunbar deeply. He knew that too many African Americans had suffered injustice and death at the hands of white mobs. Lynchings like the one the old man described were far too common in the United States of America. In one recent year, 1892, more than 160 African Americans had been executed by their fellow citizens.

As soon as the old man finished talking, Dunbar went to his desk. A poem was taking shape in his imagination, and he wanted to get it on paper. He wrote:

Pray why are you so bare, so bare,

Oh, bough of the old oak-tree;

And why when I go through the shade you throw,

Runs a shudder over me?

Dunbar wrote more stanzas in which the oak tree describes the lynching. The tree cannot forget the death of the innocent victim. In Dunbars version of the tale, a tormenting memory, and not a ghost, haunts the oak:

I feel the rope against my bark,

And the weight of him in my grain,

I feel in the throe of his final woe

The touch of my own last pain.

Many poets spend hours searching for the precise words to convey their thoughts and feelings. Dunbar was luckier than most, because words and phrases came to his mind easily. A friend of his once joked that Dunbar should hang up a sign that read, Poems while you wait.

Dunbar wrote more than one hundred poems like The Haunted Oak, poems drawn from African-American experience. His poems could be serious or sad, joyful or humorous. He celebrated the beauty of women with black skin and described the delight of an African-American father bouncing a child on his knee. Every phase of Negro life has been caught by his pen as by a camera, said W. S. Scarborough, an African-American scholar, in 1914.

African Americans memorized Dunbars verses and recited them at social gatherings. You didnt say a Dunbar poemyou performed it, said the writer Arna Bontemps, recalling those pleasant occasions. Dunbars poetry was meant to be read aloud, so African-American parents read it to their children. Proud of this great writer, they hung Dunbars portrait in their dining rooms and parlors.

White fans flocked to the many readings that Dunbar gave throughout the country. He was a popular entertainer. He was full of energy on stage and often acted out his poems. No one else could bring Dunbars words to life as well as the poet himself could. His voice was a perfect instrument and he knew how to use it, said the writer James Weldon Johnson, who was Dunbars friend.

Dunbar was also a social critic at a period of time when few people spoke out about race relations. He wrote poems, stories, and newspaper articles that expressed his outrage at discrimination in northern cities, at unequal treatment of black and white soldiers, and, of course, at lynchings. He made people thinkand perhaps think twiceabout racial problems.

Dunbar has been a role model for the African-American writers who came after him. Langston Hughes, who published his first book of poems in the 1920s, was inspired to write some of his poems after reading Dunbars work. Gwendolyn Brooks, who won the Pulitzer Prize in poetry in 1950, dreamed of being the female version of Paul Laurence Dunbar while she was growing up.

As a beginning poet, Dunbar longed, he said, to be a worthy singer of the songs of God and of nature. To be able to interpret my own people through song and story, and to prove to the many that after all we are more human than African. His goal was simple and at the same time staggering: to show, in his writing, that people of all races are more alike than they are different. Dunbar wrote at a time when many whites viewed Africa as an uncivilized place, and Africans as inferior. He bore witness to the fact that African Americans feel the same emotions that people of European descent do. The human feeling that shines through his poetry has made Paul Laurence Dunbar one of Americas best-loved authors.

Paul Laurence Dunbar grew up hearing stories and songs. As a boy in Dayton, Ohio, he often listened to his mother talk about slavery. Matilda Dunbar had spent the first twenty years of her life as an enslaved household worker in Kentucky. Now a free woman, she took in laundry from Daytons hotels. As she scrubbed stains out of tablecloths and ironed linen napkins, she told Paul about the past.