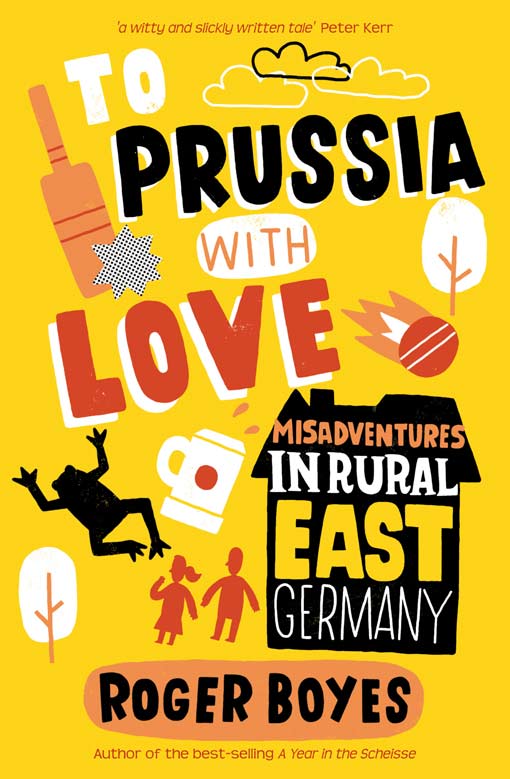

To Prussia With Love

Misadventures in Rural East Germany

Roger Boyes

TO PRUSSIA WITH LOVE

Copyright Roger Boyes, 2011

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

The right of Roger Boyes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-1-84839-955-6

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Summersdale Publishers by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 771107, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: .

Contents

Chapter 1 Dinner Ambush

Chapter 2 Truffles versus Gherkins

Chapter 3 A Whiff of Country Air

Chapter 4 Blonde Girls in Saunas

Chapter 5 The Mayor and the Frogs

Chapter 6 Our Man in Berlin

Chapter 7 Swedish Meatballs

Chapter 8 English Fried Bread

Chapter 9 Fair Play

Chapter 10 The Food of Empire

Chapter 11 An Inspector Calls

Chapter 12 Gargling with Scotch

Chapter 13 Napoleon and the Crapos

Chapter 14 Howzat!

Chapter 1

Dinner Ambush

For an expatriate, New Year's Eve is a troubled occasion. Often you have spent a claustrophobic Christmas at home in Britain confused by how the family seems to have shrunk. Irritated, too, by the fact that your mother still searches through the pockets of your discarded trousers looking for recreational drugs. So on Boxing Day, approximately twelve hours after watching The Guns ofNavarone for the sixth time and The Great Escape for the ninth time, you clear your throat and announce that you are expected at a New Year's Eve party. Back home. 'Home'. Abroad. Your parents make no effort to conceal their relief and you too tread with a spring in your stride as soon as you reach the railway station. Yet once you have arrived at the asylum of choice and for me this has been Berlin for more years than I can count on an abacus all the buried questions are dug up, like a dog searching for a bone under a rhododendron bush. How does that Clash song go again: 'Should I stay or should I go now?' Where will I be at the end of the year? With whom? Having achieved what? These were reasonable questions for a man of a certain age, a man who was tired of his profession and increasingly uncertain as to his place in the world. Berlin? Well, Berlin had become a home of sorts but nothing confirmed its alien status, or my own estrangement, more than New Year's Eve. The wrinkled and the sad stayed at home to laugh at an unfunny 1950s television sketch starring Freddie Frinton. The funky twentysomethings sweated in warehouse clubs or in seemingly spontaneous but actually precisely planned parties in apartments with bicycles in the corridor and parquet floors that threatened to give way if more than a dozen people danced at any one time. Over in the west, the burghers of the city the architects and the playwrights staged dinner parties in high-ceilinged salons. Twenty minutes before midnight the guests would finish their chocolate mousse and dutifully recite their wishes for the coming year. Sometimes that had entertainment value a husband, for example, blurting out that his special wish was that his wife would stay faithful in the coming twelve months. Yet none of this ritualised exhibition was really for me and though I had been happy to escape Incredibly Shrinking Britain, I did not relish the evening.

Outside, on the streets of the German capital, New Year's Eve is little better. The city briefly, suddenly, appears to be in the throes of a civil war; 365 days of urban anger concentrated on one evening of dull explosions and flashing lights. The Turkish kids of the battered Neuklln district setting up their rockets in bottles and firing them at other kids on the other side of the street. Smoke rising between buildings. The hiss of a Bengal Tiger hurtling upwards, then briefly pausing and, in a moment of brightness, releasing a green sparkling rain over the city, illuminating faces, flattening them as if they had no history, no problems.

What do you do? You cower under your bed, perhaps. But my dog, Mac, a West Highland terrier with the steely nerves of an organic chicken, was already there. Or you shower, dress up, pay 500 euros, and dance in the New Year. But I dance like a zombie, like someone who has just been freed from a crypt, and should not be seen performing in public.

So when Lena had suggested going out to eat, I didn't complain. I didn't even point out that booking a table for New Year's Eve as far ahead as November was somehow typically German. Lena's understanding of the national rhythm was impeccable; I had come to realise that during our almost two years together, had learned to bite my tongue. On 11 November, St Martin's Day, you

eat thick slices of goose with red cabbage and dumplings and begin the long process of fattening yourself up for Christmas. On 12 November, you make arrangements for New Year's Eve; on 13 November you start to plan your summer holiday. It was the German way; nothing was left to chance because that was the road to destruction.

'Good idea,' I had told her, pecking her on the cheek as she rushed out to work.

'I'll book at Borchardt's, maybe they've still got somewhere free.'

'Go for the loo-table.' The so-called Klo-Tisch, the table next to the toilets, was always the last to be booked. 'I love it there.'

'You're so romantic,' she said, grabbing her forgotten BlackBerry that was already flashing like a Geiger counter. 'It will be good to talk again.'

Six weeks seemed a long time to wait for a proper conversation between lovers, but it was only the slightest of exaggerations. At first our affair had seemed boundless, outside time. Then it had been steadily compressed into our working schedules. Lena was an interior decorator and the business was booming. The global economy was floundering but there was a segment of society that had money to spend: the cast-off spouses of Germany's insecure business barons. Lena called them the Desperate DAX Housewives. The DAX was the German equivalent of the FTSE index and since their alimonies were linked to the fortunes of their ex-husbands, they studied the markets more closely than any floor trader. The running costs of DAX wives were more than their precariously wealthy husbands could afford; tax advisers were telling their unhappily married clients to make a pseudo-generous settlement ('Give them one of the unsellable town houses, the snowless ski chalet in Gstaad, the gas-guzzling Cabrio and get out'). Better, it seemed, than paying the bills for a lifetime of Botox, teeth-whitening, lava stone massages and personal trainers. And what did the DAX wives want as soon as they were ensconced in their new residences? An interior designer who could reshape their habitats ('Lena, darling, make me look independent'). Lena was also doing up a place in Palm Beach and the long-haul commuting was beginning to tell; the woman I had fallen in love with a year ago used to be loose-limbed, at ease with herself; an enthusiast. Now I could see the bags forming under her eyes, hear the tired slur in her voice when taking yet another midnight call from the Palm Beach exile. 'Come back to bed,' I would say, and we would make love, me sleepy, she wound up with her head full of things to do for the following morning. It was no answer; I hated to see her lose her