Table of Contents

Landmarks

Page List

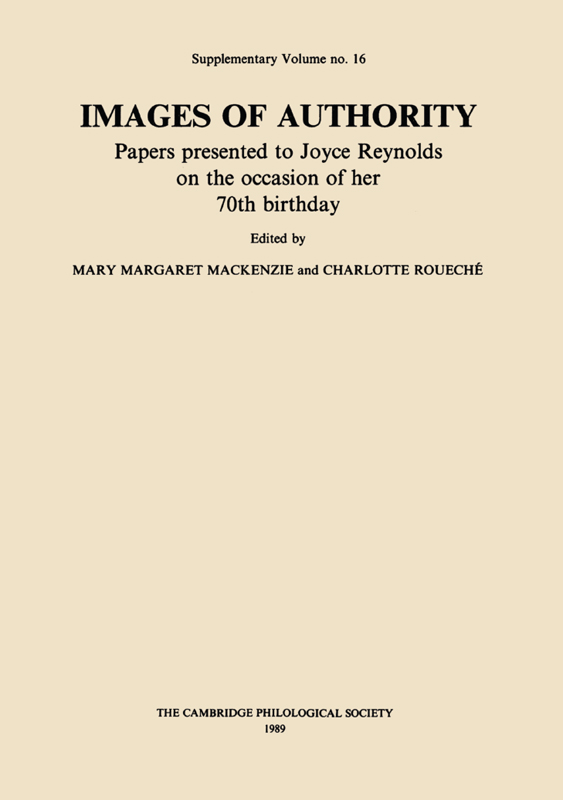

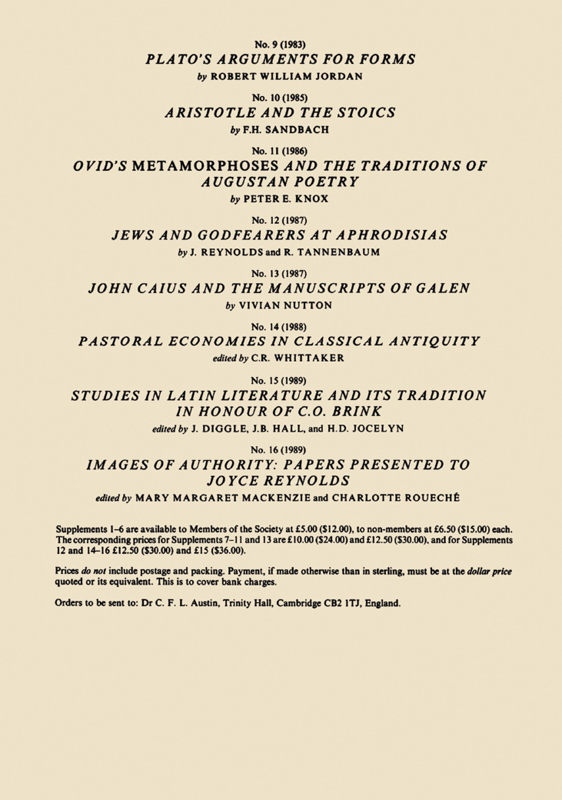

Supplementary Volume no. 16

IMAGES OF AUTHORITY

Papers presented to Joyce Reynolds on the occasion of her seventieth birthday

Edited by

MARY MARGARET MACKENZIE and CHARLOTTE ROUECH

PUBLISHED BY THE CAMBRIDGE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIETY

1989

CAMBRIDGE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIETY

ISBN 0 906014 15 8

Printed in Great Britain by the University Press, Cambridge.

CONTENTS

MARGARET ALEXIOU |

ELIZABETH ARCHIBALD |

MARY BEARD |

LUCILLA BURN |

ANNA COLLINGE |

PAT EASTERLING |

ELIZABETH FRENCH |

JANET HUSKINSON |

MARY MARGARET MACKENZIE |

SHEILA MURNAGHAN |

JANET L. NELSON |

CHARLOTTE ROUECHE |

IMAGES OF AUTHORITY

This collection of essays is dedicated to Joyce Reynolds to mark the impact she has had, both by her teaching and by her research, on the scholarly and educational world. The contributors represent the effect her teaching has had; all the articles in this volume were written by former students of hers at Newnham College, Cambridge.

She has, after all, been a significant figure in the lives of all her students. She told us what to do; and she understood both why we did it and when we did not. She taught us to think for ourselves, to question easy assumptions of authority, to refuse either to take the orthodox view for granted or to go for heterodoxy out of sheer cussedness. And she both explained and exemplified scholarship casting light on the authority of the text and the nature of evidence, the importance of careful argument and the excitement of the imagination.

When this volume was first discussed, we thought that the title Images of Authority might represent both Joyce Reynolds commitment to getting it right and her fearless iconoclasm. And so, indeed, it turned out. The responses of possible contributors showed how various were peoples conceptions of authority. Many of the papers are directly about political authority in various guises (Mackenzie, Murnaghan, Nelson, Rouech). Connectedly, there are papers on religious authority and its ambivalence (Beard, Burn, Collinge, Huskinson); and the authority to be found in other institutions (Alexiou, Archibald). Other papers again focus on scholarly or evidential authority (French, Easterling). The topic is both wide and complex. More significantly, the different perceptions of authority reveal the diversity of interests whether scholarly or ideological among the perceivers. It is striking, moreover, how often the contributors discuss both the acknowledgement of authority and its undermining. The notion of authority carries with it some reflection on its precariousness; hence our almost universal scepticism.

This is, perhaps, a part of Joyce Reynolds legacy. She has given us an image of authority, along with the techniques for looking critically at its claims to be authoritative. Her own cool scepticism has probably been the parent of ours; the editors hope that our scholarship may be a reflection, however inadequate, of the scholar who taught us. At the very least let this be a mark of our affection.

M.M.M.

C.M.R.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The editors would like to acknowledge the help of Professor Pat Easterling in compiling this volume; the advice of several anonymous referees; the excellent sub-editing skills of Nancy-Jane Thompson; and the cooperative tolerance of the contributors. We are very grateful to the Cambridge Philological Society for agreeing to publish this volume. Its production would not have been possible without the generous support of the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge, and of Newnham College, Cambridge, whom we also thank.

WOMEN, MARRIAGE AND DEATH IN THE DRAMA OF RENAISSANCE CRETE

1. An overview

In raising some preliminary questions related to the presentation and representation of women, marriage and death in the drama of Renaissance Crete, my aim is not to attempt an exhaustive analysis, nor to uncover realities, but rather to introduce three plays to a non-specialised readership from new perspectives, and to indicate how they deal in their own ways with conflicts that are both particular to Crete and of potentially wider relevance. I shall also infer that the exclusion of Cretan drama from the acknowledged literary canon of the European Renaissance is due not to aesthetic criteria, but to Eurocentrist tendencies to prioritise western masterworks. What happens when Renaissance literature moves from the centre to the margins? Cretan dramatists, although composing for noble patrons and educated bourgeois audiences (S. Alexiou 1952, 351422; Bancroft-Marcus 1983, 4776), drew also from their own traditions and experiences in adapting Italian models. This makes their works distinctively fresh and less artificial than many of their Italian counterparts. A large number enjoyed wide diffusion in popular printed chapbook form throughout the Greek-speaking world after the Fall of Crete during the period of Ottoman rule, although by that time they had fallen into disfavour with the intellectual elite (S. Alexiou 1980, (-). Cretan drama did not become part of the Greek literary canon until the 1880s, when the demoticist quest for a national language was taking over from adherents of (purist Greek) as the established medium for literary expression (Tziovas 1986, 21328). Today, Cretan drama is celebrated as a major stage in the demoticist canon, as a vital link between Byzantine and modern literature, and as a monument of national literature; but its wider significance as forged from the margins, as a blend from interacting cultures of East and West, has passed largely unrecognised. If it owed some inspiration to popular culture, as can be shown (M. Alexiou in Holton (ed.), forthcoming), it also passed back into folklore in the form of folk reworkings of literary texts as popular drama, public verse declamations, sung performances and wondertales (A. Politis 1982; Puchner 1982; M. Alexiou 1985). Condemned by most critics as unworthy of scholarly attention, this unusual Nachleben has an important bearing on the social aspects of literary reception and transmission in a culture where poetry has always played a prominent public role, and where oral traditions have remained vibrant. In this way, Cretan drama can provide a good starting-point for the study of interaction between orality and literacy on the interstices of East and West.

My task is not easy. Perhaps that is the major reason why I am honoured to contribute the present paper to Joyce Reynolds Festschrift on the occasion of her seventieth year. She taught me, in the best Newnham classical tradition, to pay attention to detail, to have respect for texts, and to pass on ones learning to the next generation. If I have departed from classical antiquity in my research and studies, her own careful work in important fields considered marginal by some has proved inspirational for me.

Very few histories of the Renaissance acknowledge the existence of poetry and drama produced on the island of Crete during the period of Venetian rule (12041669), and there are virtually no readable translations.

To sketch in the relevant background: the island of Crete, with a past stretching back to Minoan times, was always a prize possession as commercial entrepot between East and West, conveniently situated near Egypt and the coastal cities of North Africa. Part of the Roman and Byzantine Empires until the Arab conquest in the early ninth century, she was regained by the Byzantines in 961 only to pass after the Fourth Crusade of 1204 to the Venetians, who ruled her until the Ottoman conquest of 1669. She did not become part of the Greek nation-state until 1908. It has been plausibly suggested that since educated men of both Cretan and Veneto-Cretan families tended to be bilingual in Greek and Italian, while their wives spoke only Cretan Greek, the need to entertain the wives of the educated nobility and bourgeoisie contributed in a very real sense to the development of a native Cretan drama alongside the more conventional but artificial exercises in Tuscan, Italian, Latin and classical Greek fostered by the (all-male) literary academics (Bancroft-Marcus 1983, 278).