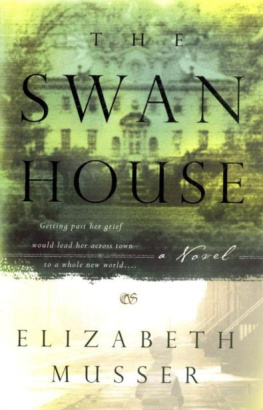

Elizabeth Kostova - The Swan Thieves: A Novel

Here you can read online Elizabeth Kostova - The Swan Thieves: A Novel full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Swan Thieves: A Novel

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swan Thieves: A Novel: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Swan Thieves: A Novel" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Swan Thieves: A Novel — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Swan Thieves: A Novel" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

SUMMARY:Psychiatrist Andrew Marlowe, devoted to his profession and the painting hobby he loves, has a solitary but ordered life. When renowned painter Robert Oliver attacks a canvas in the National Gallery of Art and becomes his patient, Marlow finds that@page { margin-bottom: 5.000000pt; margin-top: 5.000000pt; }

The Swan Thieves

Elizabeth Kostova

For my mother

la bonne mre

You would hardly believe how difficult it is to place a figure alone on a canvas, and to concentrate all the interest on this single and universal figure and still keep it living and real.

--douard Manet, 1880

Outside the village there is a fire ring, blackening the thawing snow. Next to the fire ring is a basket that has sat there for months and is beginning to weather to the color of ash. There are benches where the old men huddle to warm their hands--too cold even for that now, too close to twilight, too dreary. This is not Paris. The air smells of smoke and night sky; there is a hopeless amber sinking beyond the woods, almost a sunset. The dark is coming down so quickly that someone has already lit a lantern in the window of the house nearest the deserted fire. It is January or February, or perhaps a grim March, 1895--the year will be marked in rough black numbers against the shadows in one corner. The roofs of the village are slate, stained with melting snow, which slides off them in heaps. Some of the lanes are walled, others open to the fields and muddy gardens. The doors to the houses are closed, the scent of cooking rising above the chimneys.

Only one person is astir in all this desolation--a woman in heavy traveling clothes walking down a lane toward the last huddle of dwellings. Someone is lighting a lantern there, too, bending over the flame, a human form but indistinct in the distant window. The woman in the lane carries herself with dignity, and she isn't wearing the shabby apron and wooden sabots of the village. Her cloak and long skirts stand out against the violet snow. Her hood is edged with fur that hides all but the white curve of her cheek. The hem of her dress has a geometric border of pale blue. She is walking away with a bundle in her arms, something wrapped tightly, as if against the cold. The trees hold their branches numbly

toward the sky; they frame the road. Someone has left a red cloth on the bench in front of the house at the end of the lane--a shawl, perhaps, or a small tablecloth, the only spot of bright color. The woman shields her bundle with her arms, with her gloved hands, turning her back on the center of the village as quickly as possible. Her boots click on a patch of ice in the road. Her breath shows pale against the gathering dark. She draws herself together, close, protective, hurrying. Is she leaving the village or hastening toward one of the houses in the last row?

Even the one person watching doesn't know the answer, nor does he care. He has worked most of the afternoon, stroking in the walls of the lanes, positioning the stark trees, measuring the road, waiting for the ten minutes of winter sunset. The woman is an intruder, but he puts her in, too, quickly, noting the details of her clothes, using the failing daylight to brush in the silhouette of her hood, the way she bends forward to stay warm or to hide her bundle. A beautiful surprise, whoever she is. She is the missing note, the movement he needed to fill that central stretch of road with its dirt-pocked snow. He has long since retreated, working now just inside his window--he is old and his limbs ache if he paints out of doors in the cold for more than a quarter of an hour--so he can only imagine her quick breath, her step on the road, the crunch of snow under her sharp boot heel. He is aging, ill, but for a moment he wishes she would turn and look straight at him. He pictures her hair as dark and soft, her lips vermilion, her eyes large and wary.

But she does not turn, and he finds he is glad. He needs her as she is, needs her moving away from him into the snowy tunnel of his canvas, needs the straight form of her back and heavy skirts with their elegant border, her arm cradling the wrapped object. She is a real woman and she is in a hurry, but now she is also fixed forever. Now she is frozen in her haste. She is a real woman and now she is a painting.

CHAPTER 1 Marlow

I got the call about Robert Oliver in April 1999, less than a week after he'd pulled a knife in the nineteenth-century collection at the National Gallery. It was a Tuesday, one of those terrible mornings that sometimes come to the Washington area when spring has already been flowery and even hot--ruinous hail and heavy skies, with rumbles of thunder in the suddenly cold air. It was also, by coincidence, exactly a week after the massacre at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado; I was still thinking obsessively about that event, as I imagined every psychiatrist in the country must have been. My office seemed full of those young people with their sawed-off shotguns, their demonic resentment. How had we failed them and--even more--their innocent victims? The violent weather and the country's gloom seemed to me fused that morning.

When my phone rang, the voice on the other end was that of a friend and colleague, Dr. John Garcia. John is a fine man--and a fine psychiatrist--with whom I went to school long ago and who takes me out for lunch now and then at the restaurant of his choice, seldom allowing me to pay. He does emergency intake and inpatient care in one of Washington's biggest hospitals and, like me, also sees private patients.

John was telling me now that he wanted to transfer a patient to me, to put him in my care, and I could hear the eagerness in his voice. "This guy could be a difficult case. I don't know what you'll make of him, but I'd prefer for him to be under your care

at Goldengrove. Apparently he's an artist, a successful one--he got himself arrested last week, then brought to us. He doesn't talk much and doesn't like us much, here. His name is Robert Oliver."

"I've heard of him, but I don't really know his work," I admitted. "Landscapes and portraits--I think he was on the cover of ARTnews a couple of years ago. What did he do to get arrested?" I turned to the window and stood, watching hail fall like expensive white gravel over the walled back lawn and a battered magnolia. The grass was already very green, and for a second there was watery sunlight over everything, then a fresh burst of hail.

"He tried to attack a painting in the National Gallery. With a knife."

"A painting? Not a person?"

"Well, apparently there was no one else in the room at that moment, but a guard came in and saw him lunging for a painting."

"Did he put up a fight?" I watched hail sowing itself in the bright grass.

"Yes. He eventually dropped the knife on the floor, but then he grabbed the guard and shook him up pretty badly. He's a big man. Then he stopped and let himself just be led away, for some reason. The museum is trying to decide whether or not to press assault charges. I think they're going to drop, but he took a big risk."

I studied the backyard again. "National Gallery paintings are federal property, right?"

"Right."

"What kind of knife was it?"

"Just a pocketknife. Nothing dramatic, but he could have done a lot of damage. He was very excited, thought he was on a heroic mission, and then broke down at the station, said he hadn't slept in days, even cried a little. They brought him over to the psych ER, and I admitted him." I could hear John waiting for my answer.

"How old is this guy?"

"He's young--well, forty-three, but that sounds young to me

these days, you know?" I knew, and laughed. Turning fifty just two years before had shocked us both, and we'd covered it by celebrating with several friends who were in the same situation.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Swan Thieves: A Novel»

Look at similar books to The Swan Thieves: A Novel. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Swan Thieves: A Novel and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.