Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Copyright 2022 by Jon Mooallem

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The essays in this work, except for This is My Serious Face, have been previously published, some in different form:

A House at the End of the World, The New York Times Magazine, January 3, 2017; Why These Instead of Others as The Senseless Logic of the Wild, The New York Times Magazine, March 20, 2019; Can You Even Believe This Is Happening? (A Monk Seal Murder Mystery) as Who Would Kill a Monk Seal?, The New York Times Magazine, May 8, 2013; The Outsiders, The New York Times Magazine, July 16, 2015; At the Precise Center of a Dream as A Journey to the Center of the World, The New York Times Magazine, February 19, 2014; We Have Fire Everywhere, The New York Times Magazine, July 31, 2019; This Story About Charlie Kaufman Has Changed as This Profile About Charlie Kaufman Has Changed, The New York Times Magazine, July 2, 2020; Swing State, The New York Times Magazine, August 22, 2012; Birdman, The New York Times Magazine, March 6, 2015; A Cloud Society as The Amateur Cloud Society That (Sort Of) Rattled the Scientific Community, The New York Times Magazine, May 4, 2016; Neanderthals Were People, Too, The New York Times Magazine, January 11, 2017; and Take Me Out, The New York Times Magazine, September 21, 2021.

Hardback ISBN9780525509943

Ebook ISBN9780525509967

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Caroline Cunningham, adapted for ebook

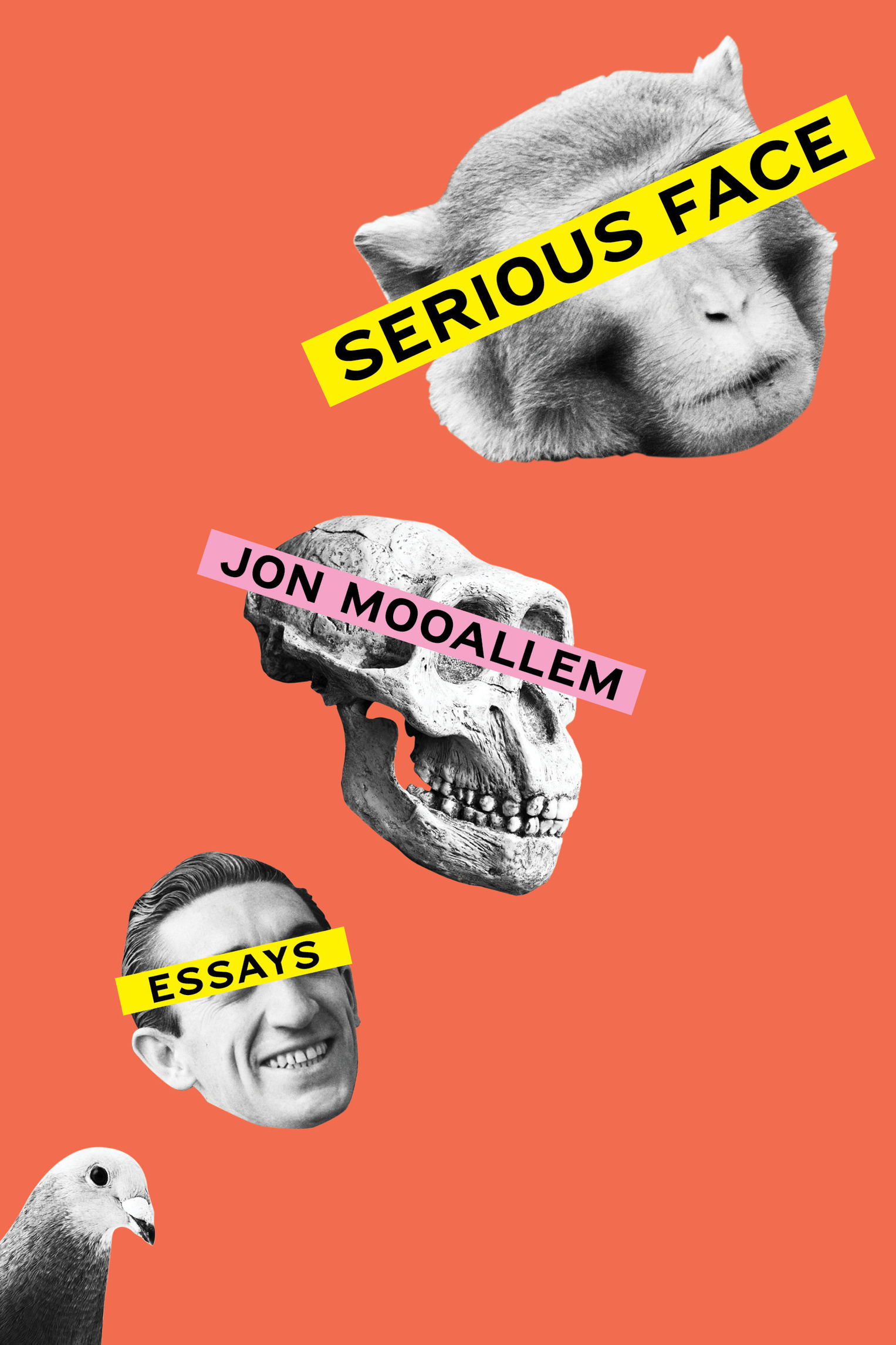

Cover design: Lucas Heinrich

Cover photographs: Michael Warren/Getty (macaque), Wlad74/Getty (Australopithecus skull), Michael Ochs Archives/Getty (Manolete), Richard Bailey/Getty (pigeon)

ep_prh_6.0_140384928_c0_r2

Contents

Introduction

Twenty years years ago, I was working at a small literary magazine in New York City, screening the bulging slush pile of poetry submissions for anything that the editors might be interested in publishing. Please know that passing judgment on all these peoples poems made me queasy. I was twenty-two years old, not especially well-read, and my only previous full-time employment had been as a kosher butcher. I could only like what I liked.

Also, I was extraordinarily sad. My father had died a year earlier, and the grief and bewilderment Id kept tamped down were beginning to burble upward. I felt alone. I felt lost. And I was fixated on figuring out why everything was so hard, what I was doing wrong. Some evenings, Id walk the fifty-eight blocks home from the office, excessively serious-faced, wrenching my mind around like a Rubiks Cube, struggling to make it show a brighter color. My point here is, Im sure this made me less patient and open-minded than I ought to have been whenever I opened another envelope from the slush pile and found someone elses delicate clump of pentameter about pear blossoms or regret.

In fact, of the thousands of poems I must have read at that job, theres apparently only one that I allowed to leave an indelible impressionand not even the whole poem, just one line. The poem is called Frost on the Fields. I know because I just went Googling for it, and found it reprinted in an obituary for the poet, Eric Trethewey, who died in 2014. Its twenty-three lines long and describes a typical November day, somewhere cold and rural: An oak leaf still stemmed to a branch tugs away and so on. Theres a pond. A hillside. A turkey buzzard on a wooden post. But then, out of nowhere, theres a question: Why are we not better than we are?

Ive been thinking hard about any common themes running through the pieces in this book, or whether theres some secret theory that explains why Ive spent almost my entire adult life so far obsessing over the process of reporting and writing them. In other words: Why these? Also: Why me?

Im tempted to say that its all utterly random. But this morning, I suddenly remembered that line, Why are we not better than we are?, and felt the clarifying, boneheaded profundity of it all over again. Im not suresincerely, Im notbut if theres a question that all these stories have at their heart, and that a reader might keep wrestling with once theyre done reading them, it could be that one. And just phrasing the question that wayWhy are we not better than we are?somehow conveys that it cant possibly be answered. Its just too damn big, like the sky.

But thats only the half of it. I also remembered the particular moment in my life when I encountered that poem, a moment when I was trying to write poetry myself, but also accepting how unnatural the medium felt to me, and wondering how long I could keep pretending. Meanwhile, I was reading magazine journalism for the first time and starting to wonder what that kind of writing was all about.

It wasnt lost on me that everything about Frost on the Fields, beyond that quick, explosive question, felt lonely and cocooned. The entire poemand I dont mean this as a knock against it as literatureis simply a guy noticing stuff on a walk, in a landscape where hardly anything is moving, where no else is around. Magazine writers, meanwhile, seemed to be circling around the same kinds of question, but only in the background while they whipped through our colossal, mystifying, stupidly beautiful world in rental cars and airplanesthe same world that I was feeling intimidated to fully enter.

I knew Id spend my life asking questions like Why are we not better than we are? Like it or not, and often I didnt, this was evidently just the way I was wired. But here was a way to channel that impulse that felt more doable to me, and more fun. Instead of thumping my head against the biggest questions of my own life, I could go ask other people specific questions about their lives, then work hard to transmit whatever feelings Id felt when I was with them and whatever insights Id stitched together or absorbed.

Id been puzzling over myself, torturously trying to unlock the truth of who I was. The truth is, I am the puzzling.

A House at the End of the World

| 2017 |

First, the backstory, because, B. J. Miller has found, the backstory is unavoidable when you are missing three limbs.

Miller was a sophomore at Princeton when, one Monday night in November 1990, he and two friends went out for drinks and, at around 4:00 a.m., found themselves ambling toward a convenience store for sandwiches. They decided to climb a commuter train parked at the adjacent rail station, for fun. Miller scaled it first. When he got to the top, electrical current arced out of a piece of equipment into the watch on his wrist. Eleven thousand volts shot through his left arm and down his legs. When his friends reached him on the roof of the train, smoke was rising from his feet.

Miller remembers none of this. His memories dont kick in until several days later, when he woke up in the burn unit of St. Barnabas Medical Center, in Livingston, New Jersey. Thinking hed resurfaced from a terrible dream, he tried to shamble across his hospital room on the charred crusts of his legs until he used up the slack of his catheter tube and the device tore out of his body. Then all the pain hit him at once.