Copyright 2008 by Richard Russo

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-0-89272-751-3

5 4 3 2

Printed on acid-free paper by Versa Press, Inc., East Peoria, Illinois

Author royalties, as well as a portion of the proceeds

from sales of this book benefit Hospice Volunteers

of the Waterville Area in Waterville, Maine.

To make a contribution, please contact:

Hospice Volunteers of the Waterville Area

304 Main St.

Waterville, ME 04901

207-873-3615

www.hvwa.org

Distributed to the trade by National Book Network, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

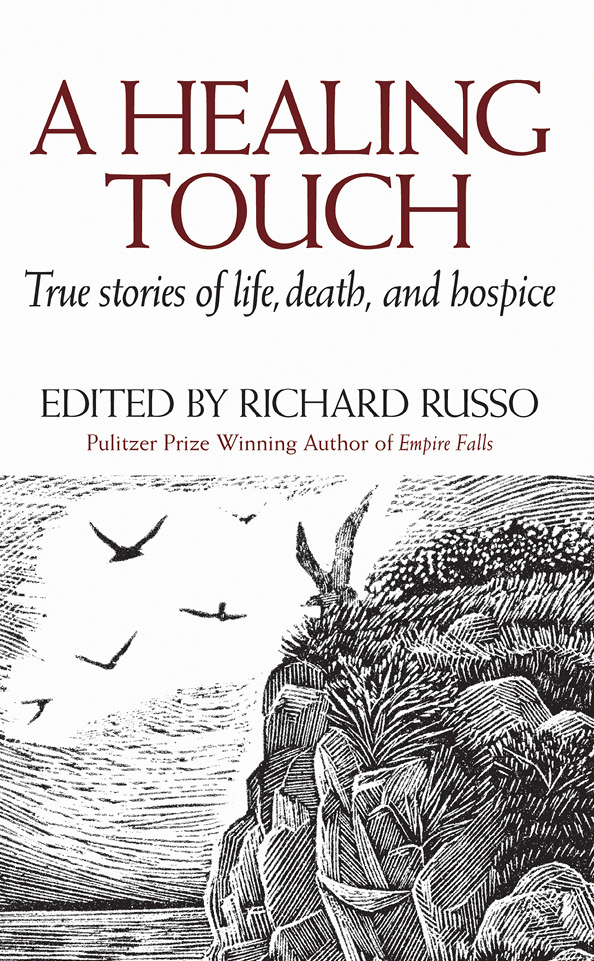

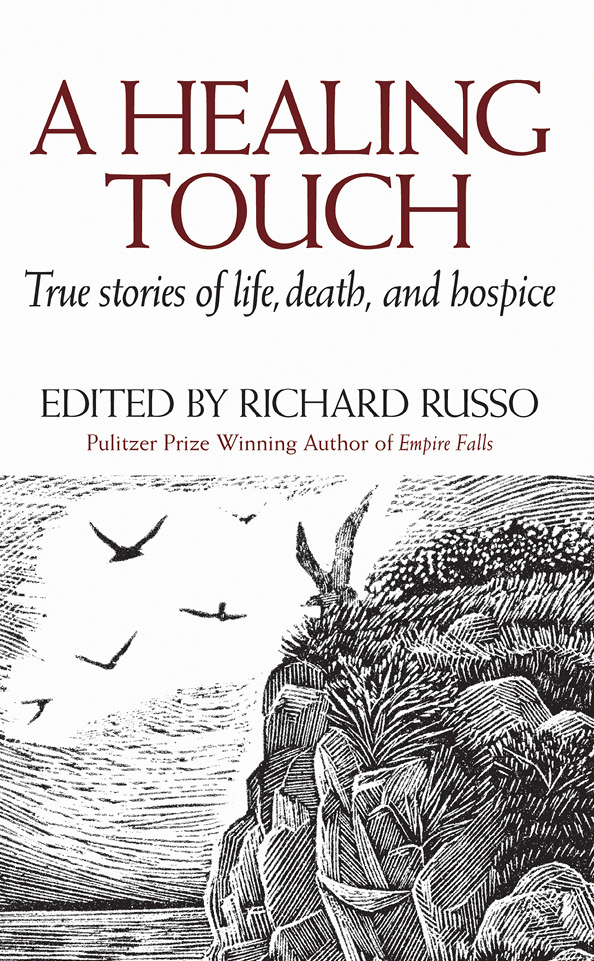

A healing touch : true stories of life, death, and hospice /

edited by Richard Russo.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-89272-751-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Hospice care--Case studies. 2. Terminally ill--Family relationships--Case studies. 3. Death--Case studies. I. Russo, Richard, 1949

R726.8.H393 2008

362.1756--dc22

2007050695

INTRODUCTION

The slender volume you hold in your hand is a collaboration between half a dozen Maine writers and a group of extraordinary people who shared with us their remarkable stories so we could share some of them with you. This books proceeds go to support the Hospice Volunteers of the Waterville Area (HVWA), and I think readers are going to be surprisedgiven the shared subject matter (theyre all linked to Hospice in some way)at just how wide-ranging these stories are. They are as varied as the services Hospice provides to its clients, as individual as the people whose experiences are being shared, as stylistically idiosyncratic as the talented writers who recount them. A friend of one of these writers, hearing about our planned project, wondered whod want to read such a book. For her, as for many people, the word hospice conjures up images of sitting in an overheated, brightly lit room, waiting for someone you love to die. But if you purchased this book, as I hope you have or will, youre going to discover something very different. Theres pain and loss, yes, but also laughter and love, faith and hard-won understanding. Life, in other words.

I want to take a moment to name all the people who offered us their stories: Dale Marie Clark, Bill Lord, Leon Duff, Kathy Jenson, Nancy Chamberlain, The Kervin Family (Ed, Sandra, Lori, and Adam), Al and Vicki Hendsbee, Sandy Hussey, Anne Murray Mozingo, Ellen Bowman, Chuck Lakin, Karen Andrews, Ed and Deb Crocker, Donna White, Deb LaVoie, Stan Spoors, Paul LePage, and Tim Robinson. Each took timein some instances a lot of itand the telling cost something, often by reopening old wounds. Sometimes their stories were cathartic, but just as often the tellers found themselves raw and hollowed out after the telling. In the beginning we writers hoped that one in three interviews would yield a story wed know how to tell. We knew that people were going to open their hearts to us, but we also knew that not every sequence of events, no matter how dramatic, would result in something that feels like a story, something with a beginning, a middle, and an end, something larger than the sum of its parts. But as soon as we started conducting our interviews, we knew wed underestimated the raw power of such human experience. Oh my God, how are we ever going to choose which story to write? we asked each other in panicked phone calls. Theyre all so wonderful. As they were. But we had to choose, and so we did.

How? You might get a slightly different answer depending upon which of us authors you asked, but I think I speak for all of us when I say that the stories we chose to write probably had as much to do with us as the stories themselves. In the end each of us chose the story we thought we understood the best, which may be another way of saying that the experience that was shared with us spoke to us in a way that we felt most competent to relate. When every story moves you deeply, you choose the one you know how to tell best. Youll see what I mean when you move from one story to the next. And I think youll see something else, too. When I approached my fellow writers with the idea for this project, every one of them said yes in a heartbeat, because the cause was good and because we were being asked to give something we knew how to give. And it was manageable. A few hours worth of interviews, a week or so to write up a draft, another few days to revise. In and out. Except it didnt work out that way. In each of these stories youll see writers becoming far more involved with their subjects than they imagined would be necessary. The tellers stories became our own. They intruded into us and we into them. They became too important to get wrong.

And were glad, since the cause couldnt be better. HVWA serves not just Waterville but twenty-seven nearby towns. Since 1980 its services and programs, all of which are free of charge, have expanded almost exponentially. In 2006 alone the number of clients in the final stages of their lives increased by 70%, participation in grief support groups by 42%, in Camp Ray of Hope by 22%. Hospice volunteers provide companionship visits, respite visits for family, compassionate listening, complementary care sessions, transportation, errand running, reading aloud, and even, as you will learn, music. There are HVWA programs for parents who have lost children, children who have lost parents, for widows and widowers, for women, for men, for whole families. Hospice helps not only the dying but also those who are left behind with the solemn duty to somehow carry on. In other words, all of us. No exceptions. Which means these stories arent theirs; theyre ours. All of ours.

Richard Russo

Camden, Maine

December 2007

I met Lee Duff over a decade ago at a place called Champions when I was teaching at Colby College in Waterville. There were no champions at Champions, at least none I recall, but there were some pretty fair racquetball players. Lee was one, I another. Lees game was a lot like Lee: pragmatic, resourceful, buoyantly optimistic. Beat him fifteen to two in the first game of the match and hell take the ball, stride to the service line, point his racket at you and say, Your ass is mine. Then, having served notice, he serves the ball, and if youre not ready, too damn bad. The last thing he wants is for you to savor your victory. Theres work to be done and hes just the man to do it. When he gets the lead, he announces the score as if through a bullhorn, an unsubtle reminder of whose property your ass is (not yours). To his way of thinking, the fact that Im fifteen years his junior is a minor inconvenience. Hes beaten me before, so why not again? His joy in what transpires on that court, win or lose, is bounded only by its walls. Trombones! he bellows, when he goes ahead seven to six. Id been playing with him a good month before I caught on to that particular allusion ( 76 Trombones, get it? get it? ).

It was clear from the start that we both derived the same benefit from sport in general, and racquetball in particular. It drains the poison, was the way Lee liked to put it, and I knew just what he meant. As a writer and teacher, I spent most of my time living in my head and trying to get my students to live in theirs, or to at least visit those heads now and then. Lee spent much of his time suffering fools, something he didnt do gladly but was part of his unofficial job description as superintendent of schools in nearby China/Vassalboro/Winslow. In the winter (half the school year in central Maine) when snow was a possibility (often), his day began at four in the morning, by which time he had to be up listening to the weather service reports in order to decide whether circumstances warranted canceling school. Canceling and not canceling it got him pretty much the same reward, a torrent of abuse from parents, teachers, and bus drivers. When school got out, thered be a different set of challenges: budget meetings, policy meetings, parent group meetings, individual parent meetings, school board meetings, disciplinary meetings (of both the student and teacher variety). As an academic, I knew all about meetings, and knew that Lee had it far worse than I did.