Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Bita

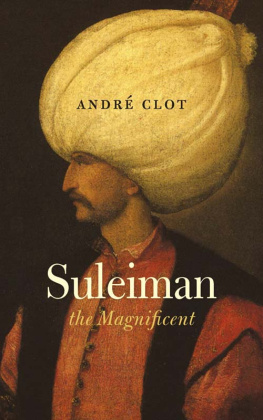

Suleyman I, tenth Sultan of the Ottomans

Hurrem, Ruthenian consort of the Sultan, known widely but erroneously as the Russian

Ibrahim of Parga, the Sultans friend and Grand Vizier, known as the Frank

Alvise Gritti, known as the Beyoglu, a plutocrat

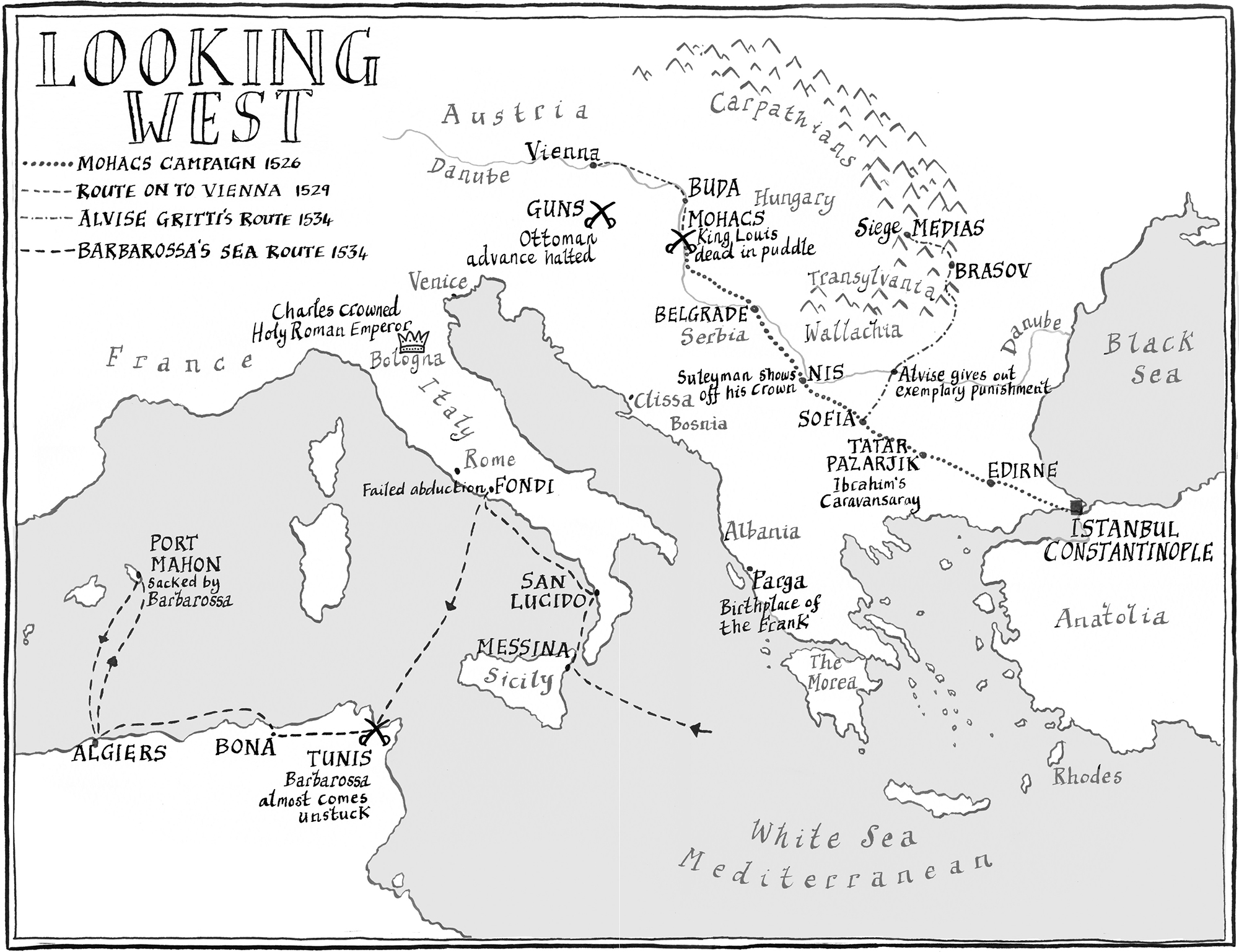

Hizir, known variously as Hayreddin, Barbarossa and the King of Algiers, a pirate

Mehmet | |

|---|

Selim | sons of Suleyman and Hurrem |

Cihangir |

Bayezit |

Mahidevran, also a consort of the Sultan

Mustafa, son of Mahidevran and Suleyman

Mehmet II, Suleymans great-grandfather, Conqueror of Istanbul

Selim I, Suleymans father, ninth Ottoman Sultan

Hafsa, Suleymans mother

Iskender Celebi, Ottoman Treasurer and Quartermaster

Figani, a poet

Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria, who will become King of the Romans, Charless brother

Francis I, King of France, known as the Most Christian King

Janos, King of Hungary

Tahmasp, Shah of Iran

Ismail, his father and predecessor as Shah of Iran

Andrea Gritti, Doge of Venice

Janos Doczy | |

|---|

Orban Batthyany | Alvise Grittis supporters, |

Tranquillus Andronicus | the Grittiani |

Francesco Della Valle |

Jerome Laski, Polish diplomat

Pietro Zen, Venetian diplomat

Marco Minio, Duke of Candia, Venetian diplomat

Cornelius de Schepper, Flemish diplomat

Marino Sanuto, diarist and failed politician

A spring morning. The Collegio meets daily in the Ducal Palace, under the Doge, Antonio Grimani. He and his cabinet of six councillors and sixteen other men of quality decide which items of business will come before the Senate. They also hear the most sensitive intelligence. Twenty-three men in robes of scarlet and blue, beneath mouldings which gleam and twist like ropes of gold. Prudence and Harmony observe from the walls. Through the open window a saltwater tang, the slap of waves. Venice.

The men shifting their posteriors on the benches of the Collegio are patricians. Their families have held power for centuries, the same names surfacing with a monotony that is at once reassuring and faintly unsavory. Venices oligarchy revolves gently, protecting it from dynastic struggles and allowing it to get on with what it does best, which is to ship things from A to B and make B pay through the nose.

A republic on a lagoon, a front without a store, Venice can only look out. On Ascension Day the Doges barge pushes off from the Lido amid a flotilla of lesser craft, their passengers straining to see His Serenity cast a ring overboard in symbolic marriage with the sea. St Mark himself was the gift of these waves, his bones smuggled out of Alexandria almost seven centuries ago and installed in the supersized chapel here that carries his name. In Venice a mans wealth is measured not in vines or acres but in bales, bolts and barrels aboard ship. Venices patricians avoid land warfare if they can help it. Admiralship brings honour, generalship merely a wage.

A sea captain weighing anchor at the Molo, the broad stone pier at the sea entrance to the Piazza, doesnt lack for secure anchorage after Venice is lost to view. Garrisoned colonies and protectorates, scattered down the Adriatic, around the Morea and further afield, offer him fresh water, fitting yards and refuge. When one takes into account Venices standing fleet, large, well-equipped and dogged in pursuit of pirates, and the Senates efficiency as a board of trade, determining which convoys should take what merchandise where, and with what escort, the Most Serene Republic of Venice the Serenissima gives every impression of being divinely fit for purpose.

Its all there in Jacopo de Barbaris recent engraving of the metropolis, not so much a birds eye view as Gods view of each tower, each wharf, each retaining wall, beyond which may be distinguished the islands of Murano, Torcello and so on, while from eight different directions cherubs fill the sails of galleys with their cargoes of cotton, indigo, gold, nutmeg, saltpetre, silver, gems, silk, pepper and grain. And there in the middle, the tiny repetitious esplanade of St Marks, and next to that, the Ducal Palace to which we now swoop, like one of Jacopos small sea-fowl, and where on this day, the eighth of April 1522, there is to be a briefing on the Turk.

After visiting his mother and washing the salt from his clothes, the returning Venetian diplomat repairs to the Collegio to deliver his report. Venice has few comparative advantages over her rivals city states and empires, for the most part, with big territories and solid alliances. The quality of the intelligence she collects is perhaps the most important.

Accuracy has made Venice the worlds information gatherer. Accuracy and speed. After King Charles of France died at Amboise on the eve of Palm Sunday, 1498, the news reached Venice before the bells of St Marks chimed for Eastertide, thirteen horses having been ridden to death in the bringing of it.

And then theres Venices pragmatism. If Martin Luther is reviling the Pope from a pub in Wittenberg, Venice receives the news without indignation, cheerfully resolved to turn it to her advantage.

Whats said in the Collegio doesnt necessarily stay in the Collegio. Transcriptions are pirated or extracts slip between the cracks and into the canals, lanes and bridges of the city, where the foreign traders, diplomats and brokers collect them and send them home, and where Marino Sanuto, the citys gadfly diarist, scoops them up for his journal. England has copies of all the Venetian reports its agents can get hold of. So does France. So does Spain.

Two recent envoys to Constantinople died shortly after coming ashore at the Molo, before having a chance to deliver their reports. Marco Minio is bucking an unfortunate trend. In mercifully good health after concluding his recent mission to the Ottoman capital, he sailed directly to the Venetian colony of Candia, which he is now administering in the name of His Serenity, and rather than let his analysis moulder, he has sent it home with his secretary. Its Minios report the Duke of Candias report, to use his new title that the Collegio has convened to hear.

It begins with a welcome pledge not to detain His Serenity with a long writing. No one wants a repeat of the epic, four-hour harangue which Andrea Gritti subjected the Senate to after he guided Venice to a disobliging draw in the War of Cambrai. Not that Doge Grimani is in a fit state to take in much of what is said. His election last year, at the age of eighty-seven, made him the oldest man ever to become Doge, and he spends much of his working day asleep.