Table of Contents

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

In the Rose Garden of the Martyrs

The Struggle for Iran

Dramatis Personae

Abdulhamit II, Ottoman sultan from 1876 to 1909, author of several pogroms against the Armenians

Abdullah, Sheikh, Kurdish nationalist commander during the 1925 rebellion.

Akbal, Nilufer, Kurdish pop star

Aktas, Ercan, entrepreneur, parliamentary candidate, son of Kadir Aktas

Aktas, Kadir, entrepreneur, sometime acting mayor of Varto, legendary Varto informer

Ataturk, Mustafa Kemal, founder of the Turkish Republic

Balikkaya, Lutfu, Kurdish nationalist living in Germany

Bayar, Celal, Democrat Party president from 1950 to 1960, ousted in the 1960 coup

Besikci, Ismail, pro-Kurdish Turkish sociologist

Bingol, Ceylan, Mehmet Serif Firats daughter

Cakar, Salahettin and Sukran, Armenian couple living in Germany

Celik, Demir, Vartos Alevi mayor

Cicek, Yakub, Kurdish nationalist now living in Germany

Darbinian, Meguerditch, Armenian boy from the village of Baskan

Demirel, Suleyman, veteran national politician of the centre-right

Dikmen, Ali Haydar, leading Varto Alevi, head of the Feron clan

Dikmen, Ekin, Republican Peoples Party deputy, son of Ali Haydar Dikmen

Dink, Hrant, Armenian newspaper editor in Istanbul

Ecevit, Bulent, long-serving politician of the Left

Erdogan, Kamer, farmer from the village of Emeran, member of the Feron clan of Mehmet Serif Firat

Erdogan, Gulseren, carpet weaver from Emeran, Kamar Erdogans sister

Ergun, plainclothes cop

Evren, General Kenan, leader of the junta that seized power in 1980, president from 1982 until 1989

Firat, Mehmet Serif, Alevi from the village of Kasman, leading member of the Feron clan, author of the History of Varto and the Eastern Provinces

Gezmis, Deniz, Turkish revolutionary, executed in 1972

Gursel, Cemal, leader of the military junta that took power in the coup detat in 1960, author of a famous introduction to Mehmet Serif Firats History of Varto and the Eastern Provinces

Halit Bey of the Cibrans, Ottoman soldier turned Kurdish nationalist leader

Han, Abdulbari, Sunni former mayor of Varto, local representative of the Islamist Justice and Development Party

Han, Ismail, head of the Varto branch of the Sultan Pir Abdal Association, nephew of Nazim Han

Han, Nazim, a.k.a. Uncle Nazim, Vartos first Alevi mayor, a leading member of the Avdalan tribe (no relation to Abdulbari Han)

Haydar (codename), PKK commander, brother-in-law of Demir Celik

Inonu, Ismet, statesman and successor to Ataturk as president of the Turkish Republic.

Karayilan, Murat, acting leader of the PKK

Kasim, Major, of Kulan, cousin of the Kurdish nationalist leader Halit of the Cibrans

Menderes, Adnan, Democrat Party prime minister from 1950 to 1960, executed after the 1960 coup

Noel, Major E.M., British intelligence officer active in Kurdistan after the First World War

Ocalan, Abdullah, a.k.a. Apo, leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK)

Osman, Nuri Pasha, Turkish military commander who re-took Varto for the government in 1925

Pamuk, Orhan, Turkish novelist, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize for Literature

Sait, Sheikh, leader of the 1925 Kurdish nationalist rebellion

Serif, Sheikh, Kurdish nationalist commander who took Harput for the rebels in the 1925 revolt

Tas, Nizamettin, Alangoz Sunni who rose to become a senior PKK commander

Xenephon, Athenian who led a defeated Greek army through eastern Asia Minor in 401 BC and described his experiences in the celebrated Anabasis, or March Up Country

Yuce, Mehmet Can, former senior member of the PKK now living in Germany

Zeynel, Ottoman-era Alevi chief and bandit

Zia, Yusuf, Kurdish nationalist leader and comrade of Halit of the Cibrans

Authors note:

The terms Bey, Aga and Efendi are Ottoman-era honorifics common among Turks and Kurds.

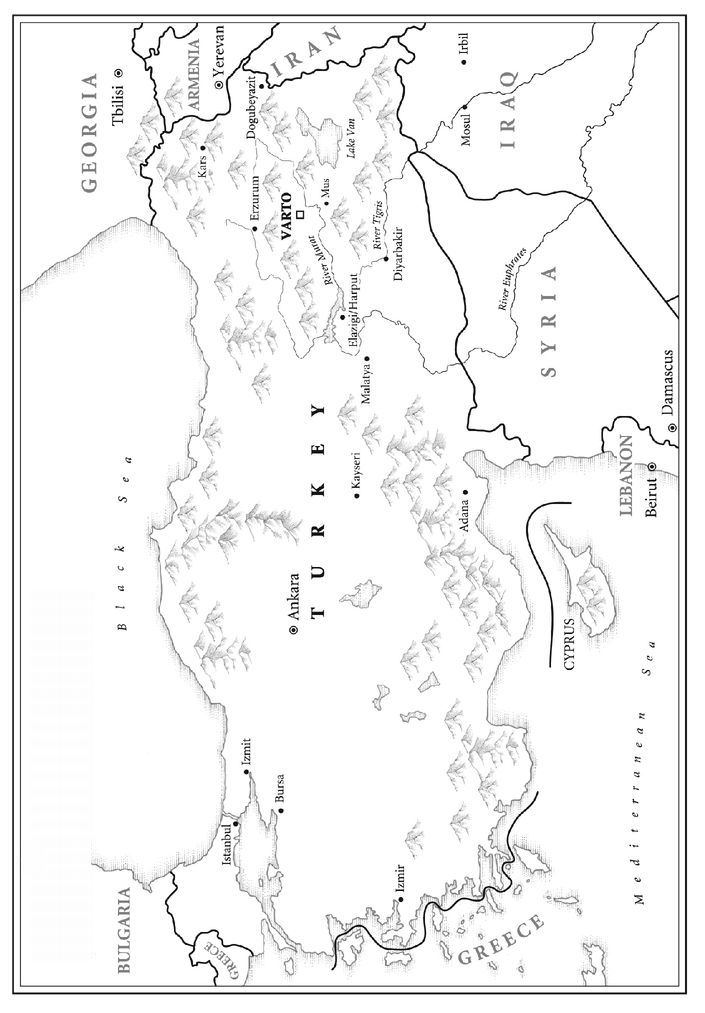

Turkey and Her Neighours

Prologue: The Mirror

I am standing in a hotel room in Mus, looking at the mirror. I have just come in the door, fleeing the downpour, and the mirror has stopped me in my tracks. It is chipped and smudged and the view it affords, of a man frozen somewhere between youth and middle age, his hair matted into sodden arabesques over a gleaming forehead, is not a pretty one. Tears of spring rain run disconsolately off my nose; my red embarrassed face, steaming industriously, anoints the scene with a grey aureole. What unsettles me is not the effect of an utter drenching, or the weariness in my eyes, which can be remedied with a towel, a change of clothes and a good nights sleep, but the fact that the image in front of me is so different from the image I have of myself. A mere six years divide me from the last time I stood before this mirror, in the same dingy room in this same stale hotel, but into those six years I have crammed what now seems like an impossible number of those rites, of passage and defeat, that mark the advent of maturity. Peering through the nimbus at my flushed, puffed up, rain-spattered features, I see with shock the degeneration that the people outside, out there in the streets of Mus, must also see.

Last time I was here in Room 205, the room they give to foreigners, I was a precocious young man. I was a foreign correspondent, which is different from being a journalist, implying curiosity rather than prurience, and a certain mildly debauched romanticism. I was in Turkey on a glamorous assignment for the Economist, arbiter of Anglo-Saxon liberal opinion; I shrugged off all weight of expectation from my pedestal of self-reliance and painless expatriate poverty. Now, my reflection tells me, I am a husband, a father, a mortgagee. But what strikes me hardest - here, of all places - is that I am no longer a Turk.

I am drying my hair now. There is a knock at the door, small enough to make my heart leap. Who could it be? Your tea, says the room boy, a surly, emaciated fellow. He has been watching me since I arrived this morning, asking questions someone else has told him to ask. I will show you how your TV works, he mumbles, entering unbidden. Our eyes fall on the objects strewn across the desk: a camera, my notebooks and some pens; a mobile; the outline of a laptop. He leaves the TV on, tuned gratuitously to CNN, then goes into the bathroom, where he informs me that red is cold and blue is hot. Then he stands at the door, with placid, bovine insistence. Nothing else, Sir? I turn off the TV, rummage through my bag and give him some lira with ill grace. A black mark from his shoes remains on the bathroom floor, but the tea he has brought is good and hot.

A love affair brought me to Turkey in 1995, from India, where I had started my career as a staff reporter on a local magazine; the love affair ended but Turkey captivated me. In Turkey, Muslim, modern and almost democratic, it would be possible to test the axiom of ineluctable conflict between Muslim countries and the West. Turkey staggered from one crisis to another: the generals, defenders of the secular order, toppled an Islamist government; the lira hit the ground with a smack; the south-east was rocked by separatist fighting; Turkey thought it was European. These were big issues, as big as any around, and there werent enough correspondents to do justice to the story. I was proud to be the youngest member of the foreign press corps, proud to talk to the foreign minister on equal terms. From my base in the dull, well-scrubbed capital, Ankara, I sought excuses to visit Istanbul: louche, suggestive, and dazzling when the evening sun struck the Bosporus, gilding the helmet domes of Sinans mosques while the gulls panted against the wind and whorls of detritus whipped down Istiklal Street. Here was a city of old men leaning on cigarettes and slamming down backgammon pieces, and of nubile young women, affectionate and cheaply dressed - relief from the white-knuckled achievers back in London. On the overnight train from Ankara, overdoing it with the arrack in a smoke-clogged dining car, I congratulated myself on inhabiting a rough, unruly, endlessly fascinating world, a battered oriental shield of Achilles to which I, more than most, had been granted privileged access.