The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

I.

II.

III.

I would like to dedicate this book to the memory of Haji Halil, a devout Muslim Turk, who saved the members of an Armenian family from deportation and death by keeping them safely hidden for over half a year, risking his own life. His courageous act continues to point the way toward a different relationship between Turks and Armenians.

PREFACE

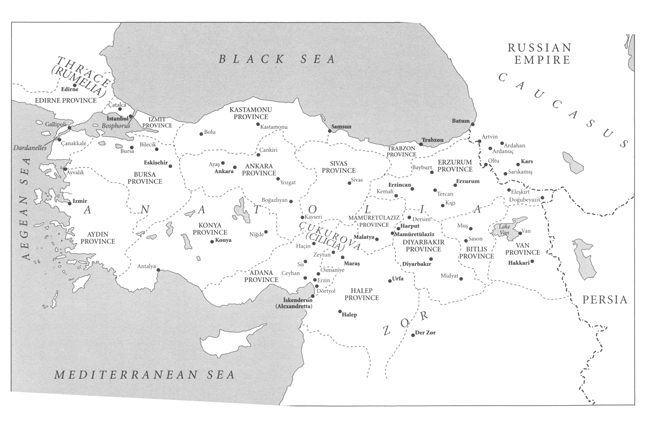

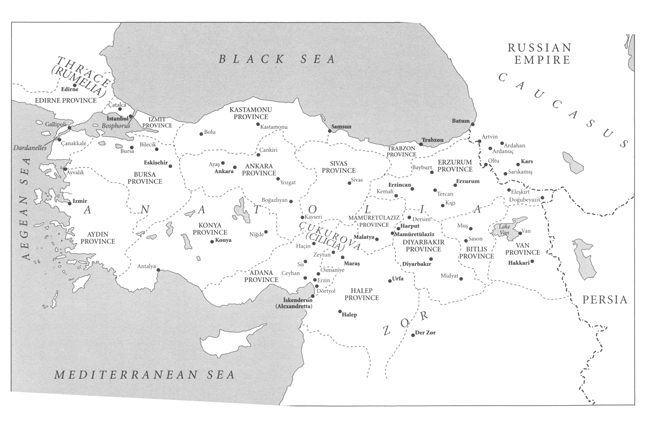

Any account of the decline and fall of the Ottoman Empire is necessarily also a history of the creation of many new nation-states within its imperial borders. Inevitably, the desire of ethnic-national groups that had coexisted for centuries to break off into their own exclusive states led to expulsion or worse for the other ethnic groups living in the same territory. Great suffering followed, suffering that formed a crucial component of each new nations collective memory. Of course, this is not unique to the Ottoman Empire: Communities, whether national, religious, or cultural, tend to memorialize not the wrongs they have inflicted but those they have endured. Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Iraq, Syriaindeed, all the entities established on Ottoman soilremember their histories as a series of expulsions and massacres inflicted on them by others. This is the basis of the historiography of nation-state building in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the Middle East. Turkish national historiography is no different, memorializing massacres of Muslims by Armenian, Greek, Bulgarian, and other ethnic-national groups while making no mention of suffering inflicted by Muslims on non-Muslim groups, such as the massacre of Christians, let alone the Armenian genocide.

This book breaks with that tradition. It is a call to the people of Turkey to consider the suffering inflicted in their name on those others. The reason for this call is not only the scale of the Armenian genocide, which was in no way comparable to the individual acts of revenge carried out against Muslims. It is also because all studies of large-scale atrocities teach us one core principle: To prevent the recurrence of such events, people must first consider their own responsibility, discuss it, debate it, and recognize it. In the absence of such honest consideration, there remains the high probability of such acts being repeated, since every group is inherently capable of violence; when the right conditions arise this potential may easily become reality, and on the slightest of pretexts. There are no exceptions. Each and every society needs to take a self-critical approach, one that should be firmly institutionalized as a communitys moral tradition regardless of what others might have done to them. It is this that prevents renewed eruptions of violence.

* * *

When on 24 May 1915 the news reached Europe that Ottoman Armenians were being killed, England, France, and Russia issued a joint declaration: In view of these crimes of Turkey against humanity and civilization, the Allied governments announce publicly to the Sublime Porte that they will hold personally responsible [for] these crimes all members of the Ottoman government and those of their agents who are implicated in such massacres. After the Allies victory in World War Iand the death of some one million Armenians (the numbers vary widely depending on the source)the Great Powers were expected to make good on their promise. However, it soon became clear during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference that the arrest and prosecution of individual members of the wartime Ottoman government would be no easy task since many of those involved in the genocide remained in power. It also quickly emerged that the Allies had divergent political interests in the region, which directly caused serious differences over the prosecution of war criminals. Finally, and most important, there were inadequate institutions and legislation within international law to deal with the problem of crimes against humanity.

While the Allied Powers had the right to prosecute war criminals and specifically the perpetrators of the Armenian massacresas granted in the 1920 Treaty of Svres, signed with the Ottoman Governmentthis prerogative was never fully exercised. There were three separate attempts, however, to try and punish the guilty. The first was the series of extraordinary courts-martial set up by the Ottoman Government itself, prior to the Treaty of Svres, in the hope of obtaining more favorable results for Turkey at the Paris Peace Conference. These courts, which began their pretrial interrogations in November 1918, started hearing cases in February the following year and continued until 1922. They were ultimately disbanded because of pressure by the Turkish nationalist movement and because the trials were no longer seen as offering any advantage to the new nationalist government, especially after the Treaty of Svres was concluded and partition of the empire had begun.

The second attempt was initiated by the Allied Powers at the Paris Peace Conference itself, with the goal of creating a legal corpus for the trial of crimes against humanity and their subsequent prosecution in an international court. Allied conflicts of interest, however, as well as the fact that international law at the time applied only to crimes committed by one state against the citizens of another doomed these efforts as well. Armenians, as Ottoman subjects, were excluded from this category and no international convention existed to cover crimes perpetrated by a state against its own people.

One final attempt to try those responsible came from Great Britain, which, wary of the Ottoman courts in Istanbul, moved to take suspects into British custody and ship them to colonial Malta. As the Turkish extraordinary courts-martial began to lose domestic support, the British continued to work to try the suspects under British law. In the absence, however, of sufficient evidence in the American and British archives against specific individualsas opposed to the Ottoman archives, which contained ample evidencetheir efforts proved fruitless. Thus, despite their many deficiencies, it was the Ottoman military trials in Istanbulthe indictments, telegrams, eyewitness accounts, and other testimony produced during the trials themselves and the investigations and interrogations leading up to themthat proved to be the most successful in documenting and establishing responsibility for the genocide.

* * *

The question of Turkish responsibility invariably prompts great controversy, but in all the debate there is only one clear question to be answered: Is there evidence of intent and central planning on the part of the Ottoman authorities for the total or partial destruction of the Armenian people? The official Turkish position is that the death of hundreds of thousands of Armenians (Turkish estimates range from 300,000 to 600,000) was a tragic but unintended by-product of the war. This argument rests on the claim that the Ottoman sources contain no evidence showing a deliberate policy of systematic killing. In this book, which makes the most extensive use to date of Ottoman materials, I will argue otherwise.