PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

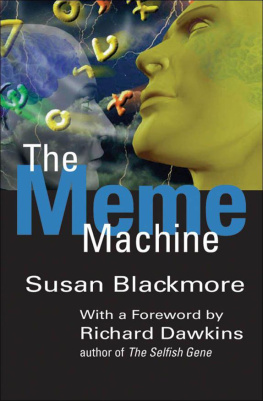

The Blackmore Country having achieved a second edition, it is proper to state that it is now presented to the public substantially in the same form as in the original issue. Advantage, however, has been taken of a friendly critique by Mr Arthur Smyth to effect some revision. Mr Smyth, who was well acquainted with the Blackmore family, and indeed a distant relation, is rather perplexed at the assertion that the novelists father was a poor man; but he certainly passed for such at Culmstock, and the fact that he took pupils, in addition to serving his poor cure, tends to show that he was by no means too well off.

In my Early Associations of Archbishop Temple it is stated with reference to the restoration of Culmstock Church: Nobody knew from what source Mr Blackmore obtained the necessary funds, but it was supposed that his wifes relations were rich. This is, in a sense, confirmed by Mr Smyth, who says that Mr Turberville, R. D. Blackmores elder brother, inherited considerable property from his mother; but, when I wrote the passage above quoted, I was not aware that John Blackmore was married twice. His first wife, who died three years after their marriage, and before John Blackmore set foot in Culmstock, may not have been in possession of means, although Turbervilles estateMr Smyth says, his will was proved for (I believe) 20,000may have been derived from his maternal connections. Mr Snowden Ward, in his Introduction to the Doone-land edition of Lorna Doone, informs us regarding R. D. Blackmore, also a son of this lady: A bequest from the Rev. H. Hay Knight, his mothers brother, put an end to his financial worries.

Nevertheless, it may be doubted whether the novelist was ever in even comparative affluence. He himself publicly declared that he lost more than he gained from market-gardeninghe was, by the way, a F.R.H.S.and the late Rev. D. M. Owen, Blackmores old schoolfellow, with whom he maintained a lifelong correspondence, told me that he was constantly complaining of his pecuniary limitations. Mr Owens reply was that he had no excuse; he had only to write another Lorna Doone to replenish his treasury to the brim. When, also, he was asked for a subscription to the Culmstock flower show, Blackmore declined, assigning as the reason that he couldnt afford it. This does not look like comparative affluence.

Mr Smyth says that he never saw or heard of any daughters of the Rev. John Blackmore. If he implies that there were none, he is certainly mistaken (see Prologue), but he raises a problem which, I confess, I am not able to solve. In Charles Church there is a marble slab erected to the memory of the Rev. John Blackmore by his children, J. B., R. B., M. A. B. No allusion is made to M. A. B. in the pedigree either by the Rev. J. F. Chanter or Mr Snell. The only explanation which occurs to me is that M. A. B. may represent the initials of their full sister, who died in infancy. The Rev. John Blackmore married in 1822. Three years later he sustained a terrible trial. The novelists father, says Mr Ward, was a coach for Oxford pupils, until, in 1825, a great outbreak of typhus fever swept away his wife, daughter, two pupils, the family physician, and all the servants, and almost broke John Blackmores heart. R. D. Blackmores mothers maiden name was Anne Basset Knight; and the A. in M. A. B. suggests that her daughter may have been called Anneperhaps Mary Anne, if M. A. B. indicates that daughter. She had long been dead, but the brothers, as an act of piety, may have chosen to commemorate her in this way, whilst ignoring the daughters of the second family, whom Mr Smyth never saw or heard of.

In conclusion, the demand for a second edition of this work is a satisfactory answer to the disparaging remarks of the late Mr F. T. Elworthy in a presidential address to the members of the Devonshire Association for the Promotion of Literature, Science, and Art. It is a bad precedent that the title and contents of a new work should be officially censured on an occasion when it was by an accident that the author was not present to be lectured for his shortcomings, just as it was a pure accident that Mr Elworthy was not named in the book as accompanying Dr Murray and Professor Rhys in their visit to the Caractacus stone on Winsford Hill (p. 109)! I now repair this omission, and at the same time express regret that the secretaries did not take steps to delete from the reports of a learned and very useful association criticism which, to say the least, was beside the mark.

F. J. SNELL.

January 30, 1911.

PROLOGUE

The Blackmore Country is an expression requiring some amount of definition, as it clearly will not do to make it embrace the whole of the territory which he annexed, from time to time, in his various works of fiction, nor even every part of Devon in which he has laid the scenes of a romance. The latter point may perhaps be open to discussion in the sense that, ideally, the glamour of his writing ought to rest with its full might of memory on all the neighbourhoods of the West around which he drew his magic circle. As a fact, however, it is North Devon and a slice of the sister county that form his literary patrimony, while Dartmoor is a more general possession, which he failed to seal with the same staunch and archetypal impression. There have been many good Dartmoor stories, and one instinctively associates that region with the names of Baring-Gould and Eden Phillpotts; with Blackmore, hardly at all. But from Exmoor to Barnstaple, and from Lynton to Tiverton, he reigns supremeand naturally, for this was his homeland, which, through all its length and breadth, he knew with an intimacy, and loved with a devotion, and portrayed with a skill, that will surely never again be the portion of any child of Devon.

Richard Doddridge Blackmore was born on June 7, 1825, at Longworth, in Berkshirea circumstance which raises the delicate and important question whether, after all, he can be justly claimed as a Devonshire man. On the whole, I think, the question may be answered affirmatively, although it is evident that he cannot possibly be described as a native of the county. Who, however, would dream of depriving an Englishman of his nationality merely for the accident of his being born abroad, unless indeed he deliberately abandoned that proud title and threw in his lot with the country of his birth, to the exclusion of his ancestral home? And this practically represents the state of affairs as regards Blackmore. In one sense it must be admitted he did not remain constant to his Devonshire connections, inasmuch as he resided through a great part of his life, and to the day of his death, at Teddington, in Middlesex. But as against this must be set the facts that he descended from an old North Devon stock, a stock so old that it may fairly be termed indigenous, and that his boyish experiences were almost entirely confined within the county. To these weighty considerations may be added that he eventually became possessor of the ancient residence of his race, that he always manifested the warmest interest in county concerns, and that his great achievement in literature was inspired by West-country legend. That well-known authority, the Rev. J. F. Chanter, worthy son of a worthy sire, would like to say Devon legend, and much may be urged in favour of his contention, notwithstanding that modern Exmoor is altogether in Somerset. He points out, for instance, that Bagworthy (or Badgery) Wood, the centre of the Doone traditions, is in Devon. Still it were better, perhaps, to consider