The Meme Machine

Susan Blackmore is a Reader in Psychology at the University of the West of England, Bristol, where she lectures on the psychology of consciousness. Dr Blackmores research interests include neardeath experiences, the effects of meditation, why people believe in the paranormal, evolutionary psychology, and the theory of memetics. She is the current PerrottWarrick Researcher, studying psychic phenomena in borderline states of consciousness, and has received the Distinguished Skeptics Award from CSICOP, the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Susan Blackmore writes for several magazines, has an occasional column in the Independent newspaper, and is a frequent contributor and presenter on radio and television.

The Meme Machine

SUSAN BLACKMORE

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0X2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys aim of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Bombay Buenos Aires Calcutta

Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul

Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai

Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw

and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Susan Blackmore, 1999

Foreword Richard Dawkins, 1999

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First published 1999

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback 2000

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press.

Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the

purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted

under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of

reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences

issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning

reproduction outside these terms and in other countries should be

sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press,

at the address above.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way

of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated

without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover

other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition

including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

(Data available)

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

(Data available)

ISBN-13: 978-0-19-286212-9

Typeset by Joshua Associates Ltd., Oxford

Printed in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

For Adam

Foreword

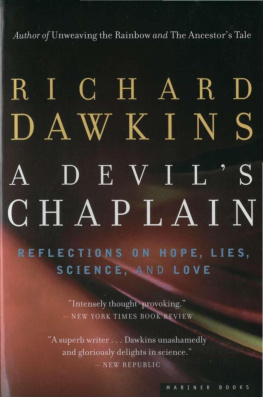

by Richard Dawkins

As an undergraduate I was chatting to a friend in the Balliol College lunch queue. He regarded me with increasingly quizzical amusement, then asked: Have you just been with Peter Brunet? I had indeed, though I couldnt guess how he knew. Peter Brunet was our much loved tutor, and I had come hotfoot from a tutorial hour with him. I thought so, my friend laughed. You are talking just like him; your voice sounds exactly like his. I had, if only briefly, inherited intonations and manners of speech from an admired, and now greatly missed, teacher. Years later, when I became a tutor myself, I taught a young woman who affected an unusual habit. When asked a question which required deep thought, she would screw her eyes tight shut, jerk her head down to her chest and then freeze for up to half a minute before looking up, opening her eyes, and answering the question with fluency and intelligence. I was amused by this, and did an imitation of it to divert my colleagues after dinner. Among them was a distinguished Oxford philosopher. As soon as he saw my imitation, he immediately said: Thats Wittgenstein! Is her surname _____ by any chance? Taken aback, I said that it was. I thought so, said my colleague. Both her parents are professional philosophers and devoted followers of Wittgenstein. The gesture had passed from the great philosopher, via one or both of her parents to my pupil. I suppose that, although my further imitation was done in jest, I must count myself a fourth-generation transmitter of the gesture. And who knows where Wittgenstein got it?

The fact that we unconsciously imitate others, especially our parents, those in quasi-parental roles, or those we admire, is familiar enough. But is it really credible that imitation could become the basis of a major theory of the evolution of the human mind and the explosive inflation of the human brain, even of what it means to be a conscious self? Could imitation have been the key to what set our ancestors apart from all other animals? I would never have thought so, but Susan Blackmore in this book makes a tantalisingly strong case.

Imitation is how a child learns its particular language rather than some other language. It is why people speak more like their own parents than like other peoples parents. It is why regional accents, and on a longer timescale separate languages, exist. It is why religions persist along family lines rather than being chosen afresh in every generation. There is at least a superficial analogy to the longitudinal transmission of genes down generations, and to the horizontal transmission of genes in viruses. Without prejudging the issue of whether the analogy is a fruitful one, if we want even to talk about it we had better have a name for the entity that might play the role of gene in the transmission of words, ideas, faiths, mannerisms and fashions. Since 1976, when the word was coined, increasing numbers of people have adopted the name meme for the postulated gene analogue.

The compilers of the Oxford English Dictionary operate a sensible criterion for deciding whether a new word shall be canonised by inclusion. The aspirant word must be commonly used without needing to be defined and without its coinage being attributed whenever it is used. To ask the metamemetic question, how widespread is meme? A far from ideal, but nevertheless easy and convenient method of sampling the meme pool, is provided by the World Wide Web and the ease with which it may be searched. I did a quick search of the Web on the day of writing this, which happened to be 29 August 1998. Meme is mentioned about half a million times, but that is a ridiculously high figure, obviously confounded by various acronyms and the French mme. The adjectival form memetic, however, is genuinely exclusive, and it clocked up 5042 mentions. To put this number into perspective, I compared a few other recently coined words or fashionable expressions. Spin doctor (or spin-doctor) gets 1412 mentions, dumbing down 3905, docudrama (or docu-drama) 2848, sociobiology 6679, catastrophe theory 1472, edge of chaos 2673, wannabee 2650, zippergate 1752, studmuffin 776, post-structural (or poststructural) 577, extended phenotype 515, exaptation 307. Of the 5042 mentions of memetic, more than 90 per cent make no mention of the origin of the word, which suggests that it does indeed meet the OEDs criterion. And, as Susan Blackmore tells us, the Oxford English Dictionary

Next page