Memes in Digital Culture

MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series

Computing: A Concise History, Paul Ceruzzi

Crowdsourcing, Daren C. Brabham

Information and the Modern Corporation, James Cortada

Memes in Digital Culture, Limor Shifman

Intellectual Property Strategy, John Palfrey

Open Access, Peter Suber

Waves, Fred Raichlen

Memes in Digital Culture

Limor Shifman

The MIT Press | Cambridge, Massachusetts | London, England

2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shifman, Limor, 1974.

Memes in Digital Culture/ Limor Shifman.

p. cm.(MIT press essential knowledge)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-52543-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN978-0-262-31770-2 (retail e-book)

1. Social evolution. 2. Memes. 3. Culture diffusion. 4. InternetSocial aspects. 5. Memetics. I. Title.

HM626.S55 2014

302dc23

2013012983

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Series Foreword

The MIT Press Essential Knowledge series offers accessible, concise, beautifully produced pocket-size books on topics of current interest. Written by leading thinkers, the books in this series deliver expert overviews of subjects that range from the cultural and the historical to the scientific and the technical.

In todays era of instant information gratification, we have ready access to opinions, rationalizations, and superficial descriptions. Much harder to come by is the foundational knowledge that informs a principled understanding of the world. Essential Knowledge books fill that need. Synthesizing specialized subject matter for nonspecialists and engaging critical topics through fundamentals, each of these compact volumes offers readers a point of access to complex ideas.

Bruce Tidor

Professor of Biological Engineering and Computer Science

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Acknowledgments

This book could not have been written without the support of a number of patient colleagues who have put up with my meme obsession over the last few years. I am indebted to Elad Segev, Paul Frosh, Ben Peters, Nicholas John, and Leora Hadas for their valuable comments on parts of this manuscript. I am particularly grateful to Menahem Blondheim, the most generous friend and intellectual I have ever encountered.

I consider myself extremely fortunate to be part of the Department of Communication at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I have benefited greatly from the wisdom and kindness of my friends in this wonderful academic home. Besides those mentioned above, other colleagues and graduate students from the departmentin particular Elihu Katz, Zohar Kampf, Keren Tenenboim-Weinblatt, Asaf Nissenboim, Noam Gal, and Lillian Boxman-Shabtaioffered many insightful observations and criticisms. The members of the Jerusalem Discourse ForumGonen Hacohen, Michal Hamo, Ayelet Kohn, Chaim Noy, and Motti Neigerraised enlightening issues in two brainstorming sessions dedicated to memes.

I started my journey to the light heavyweight side of the Internet as a postdoctoral researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute, UK. My colleagues at the Institute, particularly Bill Dutton and Stephen Coleman, fully backed my plan to study the (then) eccentric topic of Internet humor. I am also extremely grateful to danah boyd and Nancy Baym from Microsoft Research. Their ongoing support means a lot to me.

Parts of the introduction and chapters 2, 3, 4, and 6 were originally published in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker, 2013, 18[3]) and New Media & Society (An Anatomy of a YouTube Meme, 2012, 14[2]). I am thankful to the editors and publishers of those journals for their assistance and permission to reuse the papers.

My gratitude also goes to the editorial and production staff at MIT Press, particularly Margy Avery, who supported this project enthusiastically even before I knew that I wanted to write a book, and Judith Feldmann, who edited it with great sensitivity. Three anonymous reviewers offered thoughtful, constructive, and wise comments on the manuscript, and Im greatly appreciative of that.

Finally, I wish to thank my parents, Nili and Tommy Schoenfeld, my husband, Sagiv, and my children, Neta and Yuval. My love and gratitude is beyond what any meme could express.

Introduction

On December 21, 2012, a somewhat peculiar video broke YouTubes all-time viewing records. Performed by a South Korean singer named PSY, Gangnam Style was the first clip to surpass the one-billion-view mark. But the Gangnam phenomenon was not only a tale of sheer popularity. Besides watching the clip, people also responded to it creatively, in dazzling volume. Internet users from places as far-flung as Indonesia and Spain, Russia and Israel, the United States and Saudi Arabia imitated the horse-riding dance from the original video while replacing the reference to Gangnama luxurious neighborhood in Seoulwith local settings and protagonists, generating videos such as Mitt Romney Style, Singaporean Style, and Arab Style. At first glance, this whole process seems enigmatic. How did such a bizarre piece of culture become so successful? Why are so many people investing so much effort in imitating it? And why do some of these amateur imitations attract millions of viewers? In what follows, I suggest that the key to these questions lies in defining Gangnam Styleas well as many other similar Internet phenomenaas an Internet meme.

The term meme was coined by Richard Dawkins in 1976 to describe small units of culture that spread from person to person by copying or imitation. Since then, the meme concept has been the subject of constant academic debate, derision, and even outright dismissal. Recently, however, the term once kicked out the door by many academics is coming back through the Windows (and other operating systems) of Internet users. In the vernacular discourse of netizens, the tag Internet meme is commonly applied to describe the propagation of items such as jokes, rumors, videos, and websites from person to person via the Internet. As illustrated by the Gangnam Style case, a central attribute of Internet memes is their sparking of user-created derivatives articulated as parodies, remixes, or mashups. Leave Britney Alone, Star Wars Kid, Hitlers Downfall Parodies, Nyan Cat, and the Situation Room Photoshops are particularly famous drops in a memetic ocean.

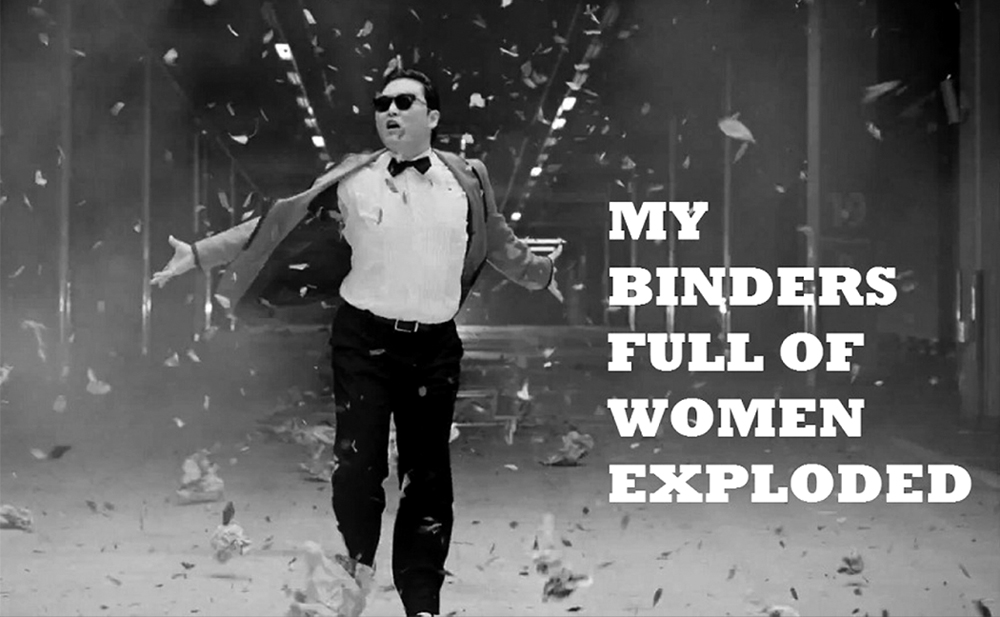

Another fundamental attribute of Internet memes is intertextuality: memes often relate to each other in complex, creative, and surprising ways. The example in figure 1 demonstrates such an amalgamate between Gangnam Style and Binders Full of Womena meme created in response to an assertion made by Mitt Romney in a 2012 US presidential debate about the binders full of women that he asked for in order to locate female job applicants for senior positions. While an eccentric Korean rapper might seem as far as one may get from an affluent American presidential candidate, meme creators managed to link them. My Binders Full of Women Exploded is thus not only a striking example of intertextuality; it also demonstrates that this new arena of bottom-up expression can blend pop culture, politics, and participation in unexpected ways.