Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

The story you are about to read describes information wars fought about the most controversial and disturbing topics in American culture in the twenty-first centuryfrom heinous anti-Black racism to pedophilia to the proper role of women in society to the merits of democracy itself. To tell this story, we rely on direct quotes from the people involved in these wars. Often, these quotes contain offensive or graphic language. We do not present these quotes to horrify, but rather to accurately expose the tenor and content of the online subcultures that have influenced the United States over the last decade. To understand the power, allure, and danger of meme wars, its imperative that these words be presented as close to verbatim as possible. However, we have redacted the most offensive language, specifically racial slurs, where we can. The information in this book is taken directly from the media output of the people fighting meme wars, including their online posts and video and audio interviews, as well as from journalist reports. But the internet is a problematic historical record because it is ephemeral. Things can be deleted from the internet, intentionally or accidentally. Some of the sources of this information have vanished since we began our researcheither because the content was taken down by internet providers or platform companies, was deleted by its author, or because the website it was posted on is no longer online. Every day, more disappears. We have done our best to archive all source material. We hope that this book will serve as a lasting record of the past decade of meme wars online.

Dont Tread on Me

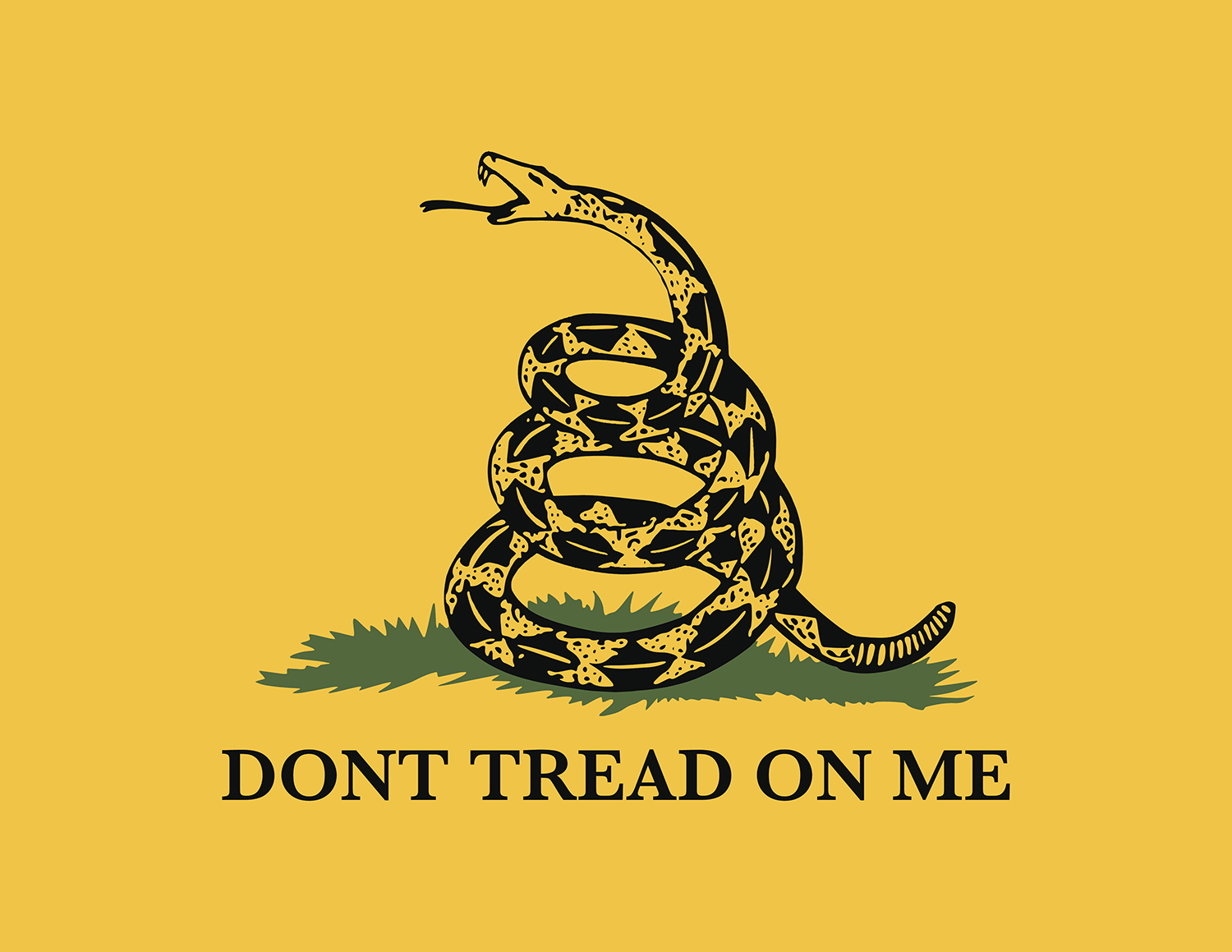

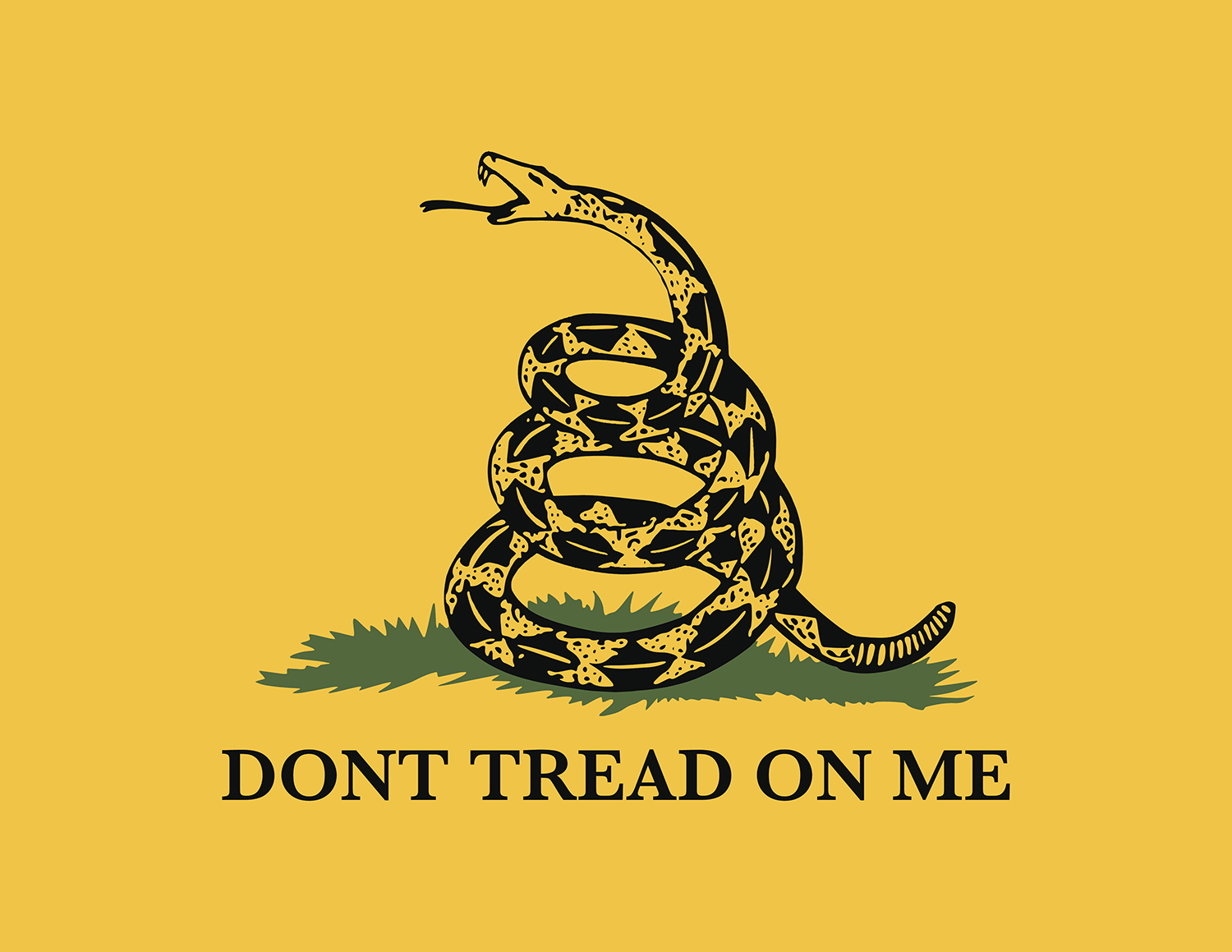

Were storming the Capitol! Its a revolution! Elizabeth from Knoxville, Tennessee, told a reporter outside the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. She had a blue Trump flag slung across her neck like a cape. As soon as she entered the Capitol, she tearfully related, police maced her in the face. As she cried into the camera, her fellow rioters walked into the frame carrying American flags, MAGA flags, Trump flags, and the familiar yellow flag with the coiled rattlesnake hissing the warning Dont Tread on Me.

As soon as this video of Elizabeth hit Twitter, it went viral. Her melodic, plaintive tone, her earnest insistence that she was part of a revolution, even her strange piano-design scarf and flag cape made her memorable. People watching the insurrection unfold live shared video of her with glee. Millions watched the chaos happen in real timeon broadcast TV, social media, and video streams that the rioters themselves dutifully posted. A very real and coordinated attempt to thwart the democratic process of America was also a surreal media spectacle, and Elizabeth was one of the minor characters.

From Twitter to TikTok, Elizabeth became fodder for internet jokes. People remixed the video with autotune. Sleuths spun conspiracies when they noticed that she held a towel with something white and round in it that she rubbed on her red eyes. Was it an onion? some speculated. Maybe Elizabeth was a liar who hadnt really been maced, and perhaps the whole insurrection had been planned (it was, but not in the way these conspiracists meant) or was a hoax (it wasnt).

Elizabeth from Knoxville had been memed. No longer a person with a real identity, now Elizabeth from Knoxville was a character, a memorable piece of media that resonated with people for different reasons. The video clip of her was recontextualized, remixed, and redistributed, carrying all sorts of meaning. Thats the definition of a meme, first coined by the biologist Richard Dawkins in his 1976 text The Selfish Gene . Supporters of the insurrection shared internet memes that focused on how Elizabeth had been treated badly by the police. People who thought the insurrection was a terrifying breach of democracy shared memes celebrating her macing, or mocking her impotent rage. These memes made clear what group the sharer was in, which is a key aspect of memes. Memes signify membership in an in-group. Sometimes they are such an inside joke that they are inscrutable to people on the outside. Yet even when they are popular and accessible, they contain a point of view and announce the positioning of the sharer. Elizabeth, in the memes, was an ally or an enemy, depending on where you stood.

She herself was clearly a member of a meme group, as her flag made clear: the MAGA tribe. And it was memes like MAGA that helped bring Elizabeth to D.C. in the first place. Along with memes like 1776!, which people had been sharing as hashtags and chanting at rallies to indicate that this January day in 2021 was, as Elizabeth had said, a revolution. And memes like the Gadsden flag, that coiled timber rattlesnake on a yellow background, itself one of the oldest memes in American history, born to express the spirit of insurgency. The Gadsden is now associated with the right, but its first iteration was created by Benjamin Franklin in 1754 as a call to unite the colonies during the French and Indian War. The snake, native to America and dignified in its approach to violence because it always warns its prey with a rattle first, was meant to embody the American spirit. It was during the Revolutionary War that the flag turned into the familiar image you see on Twitter profile pictures, bumper stickers, and lawn signs today, designed by a South Carolina politician named Christopher Gadsden (hence the name), and it has over two centuries been adopted by everyone from the Ku Klux Klan to libertarians to womens rights activists. Theres a twisted irony that a symbol of resistance to tyranny was used in an insurrection against the democratic government it was created to help form. But it makes sense that this flag would become a symbol for a homegrown insurgency; one hallmark of a lasting meme is its ability to be recontextualized, co-opted, and used against its creators.

Amid the chaos of that day, flags told the story. Insurgents plunged the flagstaff of Old Glory into the buildings windows, piercing the glass, and with it the sense of security protecting the seat of government. Rioters paraded a Confederate flag solemnly through the halls, an act that hadnt even happened during the Civil War. Outside, they held up green Kekistan flags, which most people had never seen, proudly claiming the U.S. Congress for the esoteric denizens of a meme-made country that sprang from the bowels of the internet. Plain red or blue flags with two words on them dotted the congregation: TRUMP NATION. And everywhere, the Gadsden, poised to attack.

Many of the men and women holding these banners were dressed for war, in tactical militia uniforms bedazzled with a bricolage of badges and patches, and these too bore the memes that had brought them there. Some wore shirts emblazoned with the letter Q. Others wore patches that said Veteran of the Meme Wars or signaled their membership in various militias. All their shirts, patches, and flags marked different factions, from libertarians to white nationalists, symbols signaling different affiliations with common goals, but no centralized leadership. The boldest among them broke into the Peoples House, battling police, hurling racial epithets, taking selfies, smearing feces, and spilling blood along the way.