Contents

Guide

Page List

Praise for

Let It Bang

We need more books like this: personal, emotional meditations on gun ownership... showing us all the ways in which guns take on meaning for people, and what happens when those meanings collide.

Pacific Standard

RJ Youngs Let It Bang is a penetrating and personal look at Americas gun culture that hits the mark, finding what brings us together as much as what tears us apart.

Glenn Stout, author of Young Woman and the Sea and series editor of The Best American Sports Writing

Its easy to stand outside the fray and criticize the gun-hung whites and radical rednecks defending the Second Amendment. It takes real courage to grab a pistol, head to the range, and try to understand where theyre coming from. This is RJ Youngs success with Let It Bang.

Ben Montgomery, author of Grandma Gatewoods Walk

In the often muddled debate over gun possession and gun violence, Let It Bang resonates with common sense.

Charles E. Cobb Jr., author of This Nonviolent Stuffll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible

Honest and heartbreaking, Youngs raw account of being a [B]lack gun owner in America will mesmerize readers.

Publishers Weekly

ALSO BY RJ YOUNG

Let It Bang: A Young Black Mans

Reluctant Odyssey into Guns

For my brother Ron, who never left

I would like roses to come out of the ground somewhere any time a persons voice cracks under the weight of what it has been asked to carry. I would like to do this while the living are still the living, and I dont want to hear from any motherfucker who isnt with the program.

HANIF ABDURRAQIB

I aint scared of you motherfuckers.

BERNIE MAC

Contents

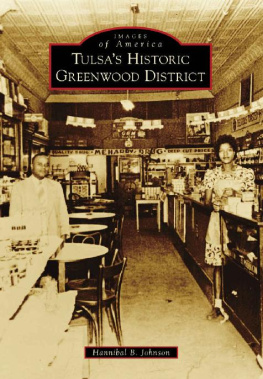

I N 1921, OTTAWAY W. GURLEY WAS THE RICHEST AND MOST powerful Black man in Tulsa. He had been among those on the starting line at the edge of Kansas and Oklahoma Territory for the Land Run of 1893. He was a Black man among thousands who traveled west and made stakes with their names written on them to stick into the ground and claim their parcel. He was twenty-five years old then, the son of two former slaves, born on Christmas Day 1868 in Huntsville, Alabama, though he grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where he finished enough school to become a teacher and then an employee of the United States Post Office Department. He was ambitious and enterprising. Learning that the U.S. government had recently purchased 6,361,000 acres of land from the Cherokee Nation, Gurley sensed an opportunity to make his family upwardly mobile and seized it. Gurley believed what Massachusetts senator Henry L. Dawes believed. Dawes saw the Cherokee Nation as a capitalists nightmare and a socialists utopia. Only one of those ideas has been allowed to flourish in the United States, and he was, like Gurley, determined not to let the future state of Oklahoma be an outlier. Upon returning from a visit to the Cherokee land in Indian Territory that would later become the state of Oklahoma, Dawes delivered his thoughts before a group at Lake Mohonk in New York: The head chief told us that there was not a family in that whole nation that did not have a home of its own. There was not a pauper in that nation, and the nation did not owe a dollar. It built its own capitol... and it built its schools and hospitals. Yet the defect of the system was apparent. They have got as far as they can go because they own their land in common. It is Henry Georges system, and under that there is no enterprise to make your home any better than that of your neighbors. There is no selfishness which is at the bottom of civilization. This was a philosophy Gurley believed in, too, this enterprise of taking what was once communal and sectioning it into a district powered by capitalism. For him, Dawes was prescient, not pernicious. Six years after the formation of the Dawes Act of 1887, which led to the creation of the Land Runs of 1889 and 1893, Gurley, former postal worker, an employee of one of this nations oldest institutions, wanted a parcel of this manifest destiny.

On September 16, 1893, fifty miles south of the Kansas state line, Gurley drove his stake into the ground just outside what would become one of the first towns of Oklahoma. Five days later, the town of Perry was incorporated. Gurley ran for county treasurer, though he was defeated. He became the towns school principal. As Perry expanded with cattle ranches and wheat farms, bars and restaurants opened to accommodate the growing citizenry. Gurley opened a profitable general store, yet he wanted more for his family, wanted to continue moving up, hunting the American Dream.

In 1905, just outside an Oklahoma town called Tulsa, oil was discovered.

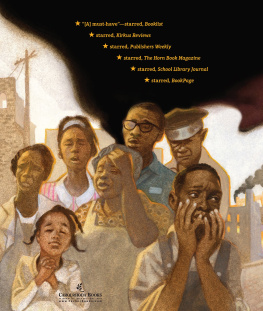

The oil boom created jobs and opportunities for businessmen, including Black businessmen. Black visionaries like Edward P. McCabe, Robert Reed Church, and W. E. B. Du Bois implored Black folks to move from the South, where the promised Reconstruction was failing, to Oklahoma. Gurley recognized a unique opportunity in Tulsa: an all-Black district on the outskirts of a town, creating oil-baron millionaires overnight. Black folks flocked to Tulsa, which citizens nicknamed Magic City. In swift order, Black folks worked together to transform forty-acre lots into a city within a city, nearly forty blocks of Black-owned and Black-operated businesses, from movie theaters to clothing stores, and including offices for local doctors, lawyers, and clergymen.

In 1905, Gurley sold his general store and land in Perry and moved his family. He bought forty acres just outside Tulsa, north of the train tracks that ran through the city limits. It was Gurley who opened the first grocery store in the area. In that same area, he met John the Baptist Stradford, who went by J.B. The two became friends and informal partners while building a Black community on a foundation of pro-business as philosophy. But Gurley and Stradford were no fools. They knew racial animus would find thempolitically, socially, violentlyoutside of their enclave. Each sought to insulate himself, his businesses, and the growing district in an area that city architects called Greenwood.

Greenwood was annexed to Tulsa in 1909 and stretched north from the Frisco railroad tracks to Independence Avenue, east to the Midland Valley railroad tracks, and west to Cheyenne Avenue. The Greenwood District grew faster than the city of Tulsa, outpacing the growth of Tulsa at large by 2 percent. In 1907, the year Oklahoma achieved statehood, 1,422 Black folks lived there. By 1910, three years later, 2,754 Black folks lived in Greenwood; by 1919, more than ten thousand.

The district was home to two high schools, Dunbar and Booker T. Washington; two newspapers, the Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun; and three lodges, two theaters, a hospital, a library, and thirteen churches. Outside the district, Tulsa lacked both job and housing opportunities for Black folks. If they were fortunate to find work at all, it was as domestics and live-in servants for rich, white households. Greenwoods rapid development filled this absence, providing a pathway to wealth and stability. Journalist and publisher Andrew Jackson Smitherman wanted to see a pathway to racial equality too. Smitherman, who went by A.J., called his most famous newspaper the