This book is dedicated to my father, who combined supreme honesty with a supreme talent for imagining and reimagining.

We miss you and love you.

I cant believe that! said Alice.

Cant you? the Queen said in a pitying tone. Try again: draw a long breath, and shut your eyes.

Alice laughed. Theres no use trying, she said: one cant believe impossible things.

I daresay you havent had much practice, said the Queen. When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes Ive believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.

I know where it started, this fascination with lies. I know when: 9 January 1995. But if I know those two things, the events themselves are faint.

I was walking to a bus stop. I was well, happy, possibly care-free. Then suddenly, I collapsed.

A few decades later, I can guess at the long seconds, the confusion, the panic.

Why was I on the ground? What was happening? It made no sense.

My scarf. It was my scarf. I thought my scarf was strangling me.

I clutched at it. But the harder I fought, the tighter it got. I could not breathe.

My head, my body, my senses they were all failing.

Why.

Was.

I?

There was no

Air.

The report said I kept fighting. But there was nothing I could do. There had been no warning and now my chest was shutting down. I was a healthy, fit twenty-year-old. No pre-existing medical condition. No clue. Just sudden and complete failure.

My heart had stopped.

But somehow, they restarted it.

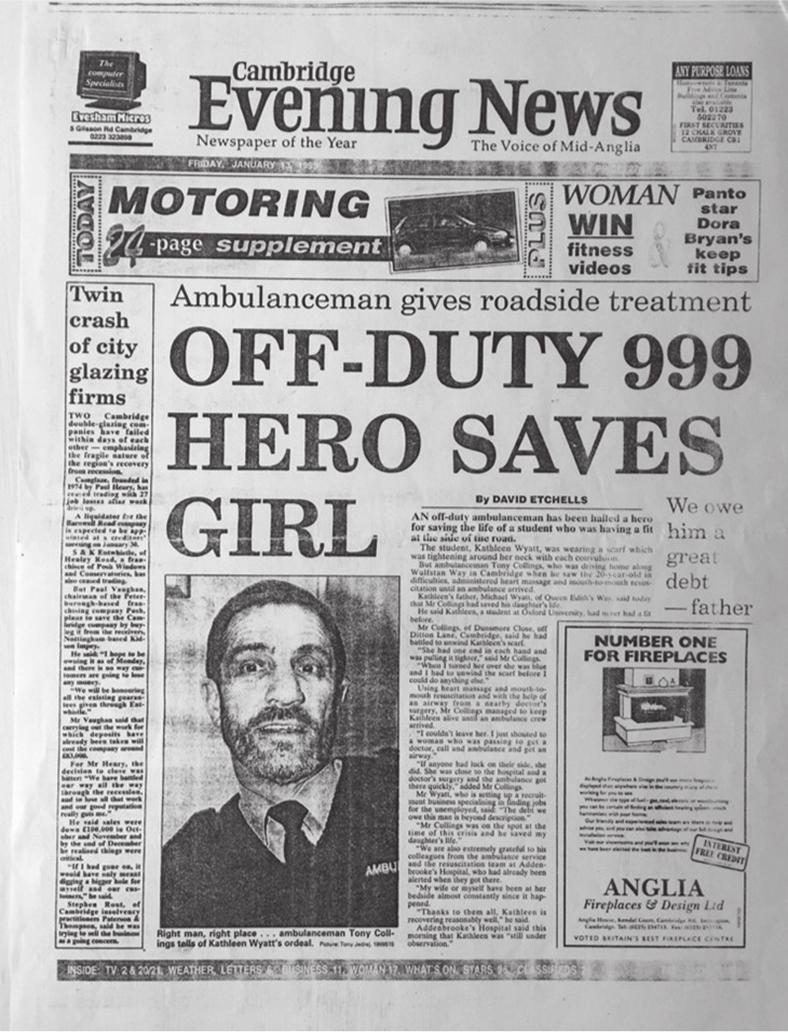

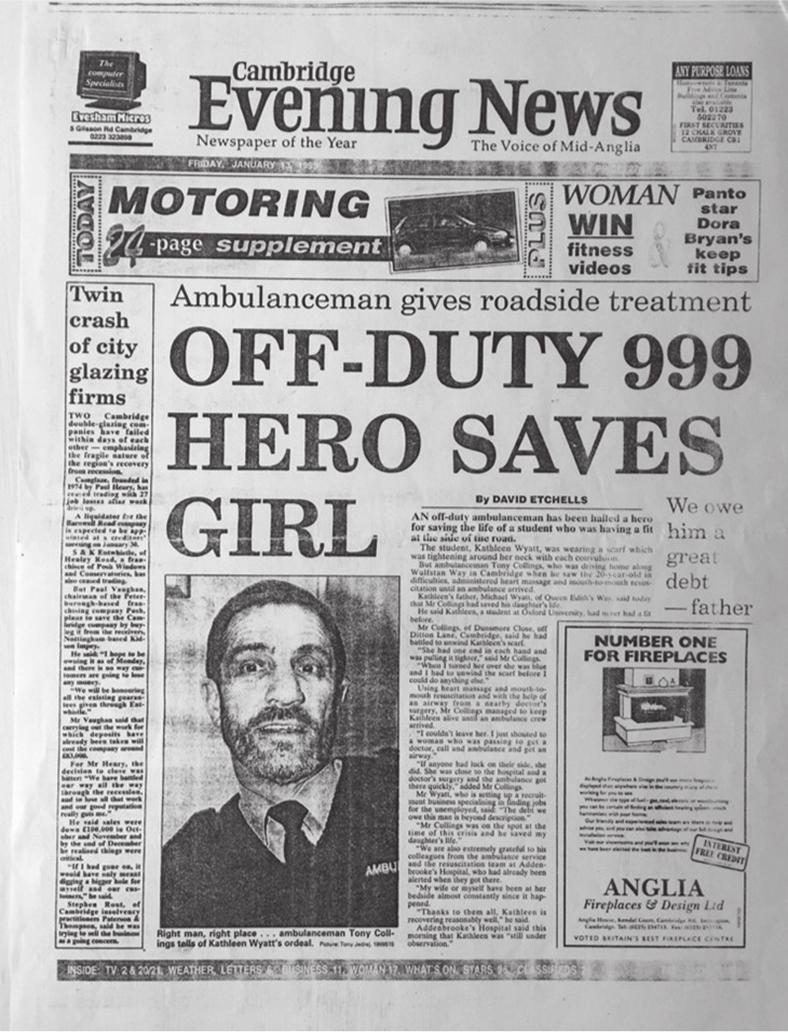

Off-duty 999 hero saves girl. It was the front-page headline in the Cambridge Evening News. Below, it read: An off-duty ambulanceman has been hailed a hero for saving the life of a student who was having a fit at the side of the road. The collapse happened so quickly that my first reaction was to rip at the tight piece of fabric around my neck. I remember none of this, but my familys recollections and a black-and-white photocopy of the front page stand as a record.

The paramedic, Tony Collings, said: I couldnt leave her. My father was quoted too. The debt we owe this man is beyond description. My father later kept in touch with Tony. I did not. And only now do I understand that I was afraid to see him. What had happened? Why did I collapse? Was it all my fault?

It was the end of the Christmas holidays after my first term at university. I was at my parents house, studying for exams. I planned to catch the bus into town to return some library books but then, it happened.

We had only recently moved house, from one side of Cambridge to the other. The move put us within five minutes drive of the largest hospital in the area, Addenbrookes. Tony was driving home after his shift but made an unplanned detour to pick up a birthday card.

He was pulling into the shops when he saw me. I had collapsed metres from the bus stop. Just round the corner was a doctors surgery. Nearby, a payphone. As Tony told the newspaper, he realised I was in difficulties. He ran to my aid, got someone to fetch an airway from the surgery and someone else to use the payphone to alert the hospital. Few people had mobiles in those days, and payphones often did not work. This one did. Those casual facts and Tonys quick action saved my life. If anyone had luck on her side, he said, she did. It was not a fit, as the reporter had written: it was a cardiac arrest.

Cambridge Evening News, 11 January 1995

Published with kind permission of Reach plc

The ambulance crew tried twice to restart my heart, but it was not until they tried the more powerful defibrillator in the hospital that it started beating again. Tonys guess was that my heart had stopped for about ten minutes. I was in a coma for thirty-six hours, and when I came to, I had lost my memory.

I responded to my name and recognised friends and family, but if someone had asked me their names or why they were there, I would have been blank. In the subsequent months and without any sense of it, I started learning how to be me again.

The first few weeks were uncertain. My brain had swelled and the specialists were unsure if there would be any long-term effects. The amnesia lingered. Doctors, nurses, loved ones came in and out of the different rooms I was in, but I could make no sense of it. Why was I there?

I stayed in hospital for six weeks until the medical team operated on me and fitted a heart device. It was an implantable cardioverter defibrillator and it would intervene if ever my heart went into another irregular rhythm. The main box with the battery sat just below my left rib cage, its wires passing through my veins and into my heart. It meant I no longer needed constant medical supervision. If my heart stopped again, I would have back-up power. Not long after Valentines Day, I left hospital with what felt like a new heart.

I have had three other heart devices since, as the technology improved and older models needed replacing. None of them has ever gone off and I have never since had a problem with my heart. Despite numerous tests over many years, my case remains medically unexplained. In 2010, I had the last defibrillator removed. The surgeries had started to take a greater toll on my health than the benefits I got from this highly sophisticated back-up plan. I had been lucky, lucky beyond belief but now my body was protesting.

What caused the cardiac arrest? The specialists could never find a clear explanation, but back then, the name they gave it was Sudden Death Syndrome. The adult version of cot death.

I returned to university and slowly resumed my studies and my life. Five years later, I wrote a piece about it in The Times. I had just started at the newspaper, first doing work experience, then on the arts desk, and it was my first lead feature. It was a big moment. But although I told the story as carefully as I could, I left something out. Something significant. Fear lurked behind my tidy, journalistic words.

I lied then, as I had before. Guilt and shame silenced me. Because on New Years Eve 1994, ten days before my sudden death, I had taken class-A drugs at a party. Could that have been the cause? I did not write about it.

When I was rushed to hospital, my friends had a difficult choice to make. Should they tell my horrified parents about the drugs? Would that knowledge give my parents comfort, or hurt them even more? Tests revealed nothing in my blood and the only damage to my heart was likely to have been caused by the collapse. The medical team chalked it up as an unknown.

My friends had summoned their courage and told the doctors about the drugs but decided not to tell my parents. And because I was over eighteen, they could also ask the doctors not to tell them. The lie was brave and kind, and it was decided by a group of friends. When the doctors were asked to keep the truth quiet, it became an institutional lie. A silence that heals. Soon it would become my lie too.

As I woke, and began to recover, parts of my personality seemed to return. But it took time. Those close to me had to put up with the wearing routine of telling me what had happened, seeing some kind of understanding dawn over my face, only for me to then look puzzled and greet them again with unfeigned pleasure.

How lovely to see you!

Silence in the room.

But why are you here? And so it went on.