Contents

Guide

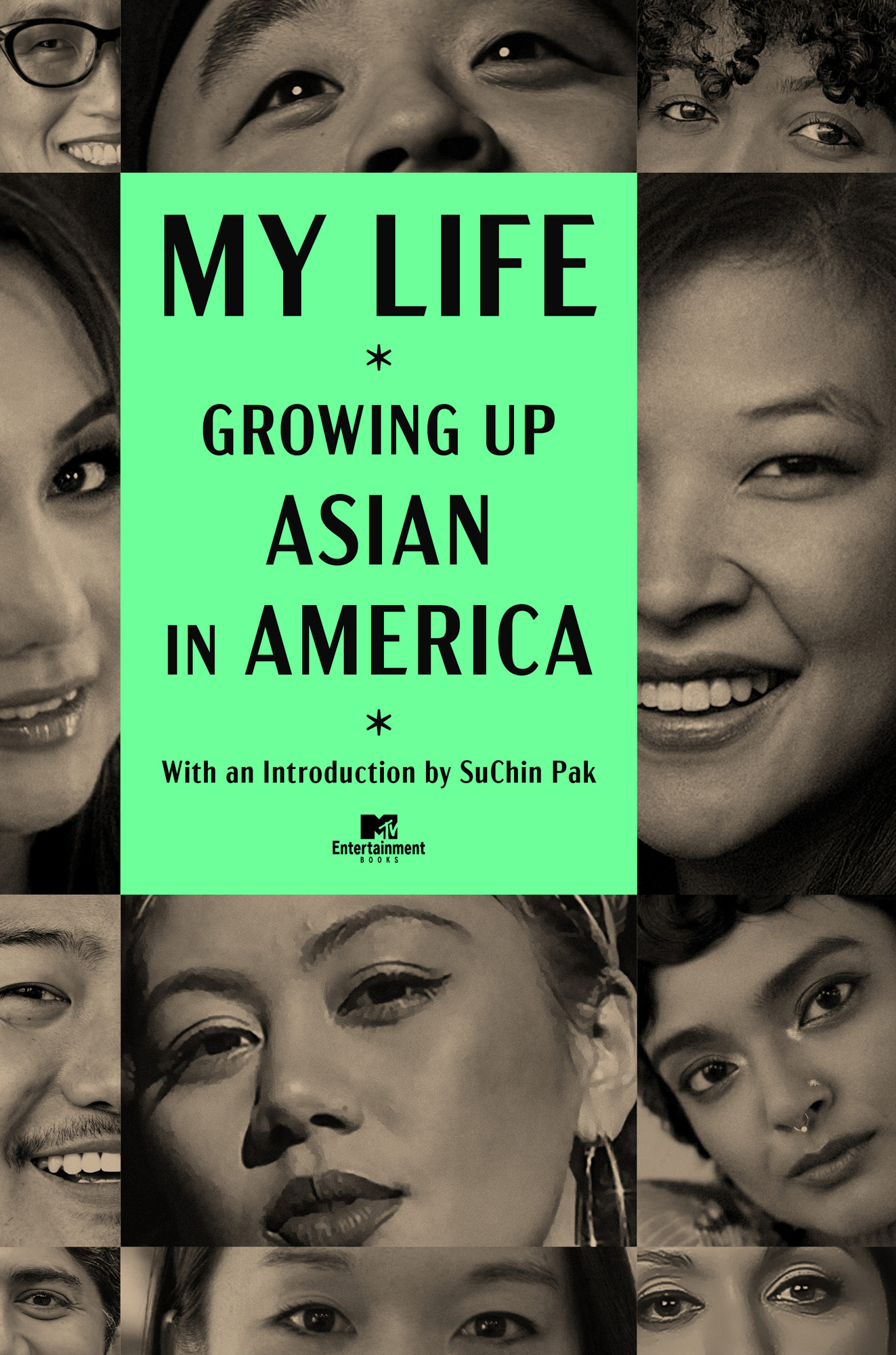

My Life: Growing Up Asian in America

With an Introduction by SuChin Pak

Logo: MTV Entertainment Books

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Compilation and Introduction copyright 2022 by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Time copyright 2022 by Teresa Hsiao

Listen Asshole copyright 2022 by Douangsyvanh Vilayphonh and Michelle Myers

Rishis Night: A One-Act Monologue Play copyright 2022 by Moss Perricone

I Dont Want to Write Today copyright 2022 by Shing Yin Khor

Destiny Manifest copyright 2022 by HRina DeTroy

Going Country copyright 2022 by Nathan Ramos-Park

Confessions of a Banana copyright 2022 by Heather Jeng Bladt

Bangla, in Black and White copyright 2022 by Tanwi Nandini Islam

The Ring copyright 2022 by Amna Nawaz

a bad day copyright 2022 by Douangsyvanh Vilayphonh

Fourteen Ways of Being Asian in America over Thirty-Six Years copyright 2022 by Melissa de la Cruz

Why We Dont Always Fight copyright 2022 by Edmund Lee

A Pair of Shorts copyright 2022 by Kao Kalia Yang

Slingshots of the Ignorant copyright 2022 by Aisha Sultan

Untitled copyright 2022 by Trung Le Nguyen

Things Better Left Unsaid copyright 2022 by Ca Dao Duong

How Do I Begin to Speak of Your Perfection? copyright 2022 by Sokunthary Svay

On Being Black and Asian in America copyright 2022 by Kimiko Matsuda-Lawrence

An Incomplete Silence copyright 2022 by Kim Tran

Ten Things You Should Know about Being an Asian from the South copyright 2022 by George Yamazawa

Unzipping copyright 2022 by Riss M. Neilson

The Question copyright 2022 by Mark Kramer

Working While Asian copyright 2022 by Ellen Pao

Facing Myself copyright 2022 by David Kwong

Places copyright 2022 by Gayle Gaviola

My First Rodeo copyright 2022 by Yoonj Kim

The Next Draft copyright 2022 by Aneesh Raman

Museum in Her Head copyright 2022 by Xiwei Lu

Afterword copyright 2022 by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Portions of this work were previously published, in slightly different form, in other media.

MTV and all related titles, logos, and characters are trademarks of Viacom International Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First MTV Books/Atria Books hardcover edition May 2022

and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Kyoko Watanabe

Jacket design by June Park

Jacket author photos: Melissa de la Cruz Maria Cina, Teresa Hsiao Kyle Lau, Kimiko Matsuda-Lawrence Jess Acosta, Amna Nawaz Tony Powell, Riss M. Neilson Jadin Cagnon, Ellen K. Pao Charlie Grosso, Suchin Pak Jesper Norgaard, Aneesh Raman Haley Naik, Nathan Ramos-Park Andrew Age, Tanas Lomi (Thelomicompany.com), G Yamazawa Kevin Yang

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-9821-9535-9

ISBN 978-1-9821-9537-3 (ebook)

Introduction

There is a Korean word, han, that is essential to our identity. Like a lot of very culturally specific words, the definition is hard to pin down. But it is, in essence, an emotional state of being that is somewhere between deep sorrow, resentment, and anger. Many Koreans equate this emotional state to a fire that sometimes rages and sometimes quietly smolders. This internalized energy can be destructive, but at times it is from this fire that we can find the seeds of our courage. Han captures the complicated quality of where I am today in my understanding of courage, better so than the American idea, which is always the fighter, the first one into battle, or the leader of the protest. I find that version of courage to be limiting and self-defeating. By that definition, I am a coward, which I know is not true.

As I write this introduction during the summer of 2021, courage has been on my mind a lot because Ive been afraid so much lately. The rise in anti-Asian hate crimes that began in 2020 has made me scared for the safety of my parents and of my kids. I keep going back to the images and videos of our elders and our women especially, who have been spit on, beaten, and threatened because they are considered foreign menaces. And yet, in all the years I have been in the media, I have never seen such a public outpouring of our courage. I have never seen people share the stories of our isolation and fear in such a vocal way. And it moved me to share my own pain, something that I never imagined doing. And in this outpouring, so many of us, myself included, have found a way into courage that is as complex as our sense of who we are as Asian Americans today.

When I was a teenager, courage basically meant never saying no. It meant never wanting to miss out on an opportunity and saying yes to things that felt bigger than my own small world. As a high school junior, I said yes to an offer to host a weekly teen show that aired on my local news channel, not knowing then that this would be the biggest turning point of my life. Being a TV journalist wasnt my dream just yet, because even though I was working on television, I never once thought that I could actually make a living as a journalist. TV reporters looked like Diane Sawyer and Barbara Walters, not sixteen-year-old Korean American girls with frizzy bobs and acne. Yes, I had Connie Chung to look up to, but there was this sense that America had its one Asian American anchorthe job had been filled. I figured I would ride this stroke of luck as far as it would take me, and then my regular plan of becoming a lawyer, like a good Asian daughter, would resume.

Right from the beginning, cameramen told me to open my eyes and squint less. It was always embarrassing to hear, to have my insecurities about the way I lookedso different from what an American should look likevalidated again and again by people I felt had the right to pass this kind of judgment. But if being successful on their show meant adjusting my appearance, I was willing to pay what felt like a small price. Like most Asian American women, I had a lot of training to appear less Asian and more white. I have memories of sitting with my glamorous Korean aunties, who regularly praised how fair my skin was and how beautiful I would be as soon as I could get my eyes done. I have a roll of film from a summer in Hawaii spent with my cousins when I was nine, where in every single shot I am raising my eyebrows as high as they will go, giving me a perpetual look of shock. But my eyes are, indeed, wider. Eventually, I experimented with tape to fold my lids into a rounder shape. I practiced facial exercises that would slim my jaw and open my eyes. I did everything I could to take the cameramens helpful tips to heart and thanked everyone around me, all the time, for the absolute privilege of the opportunity.

and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.