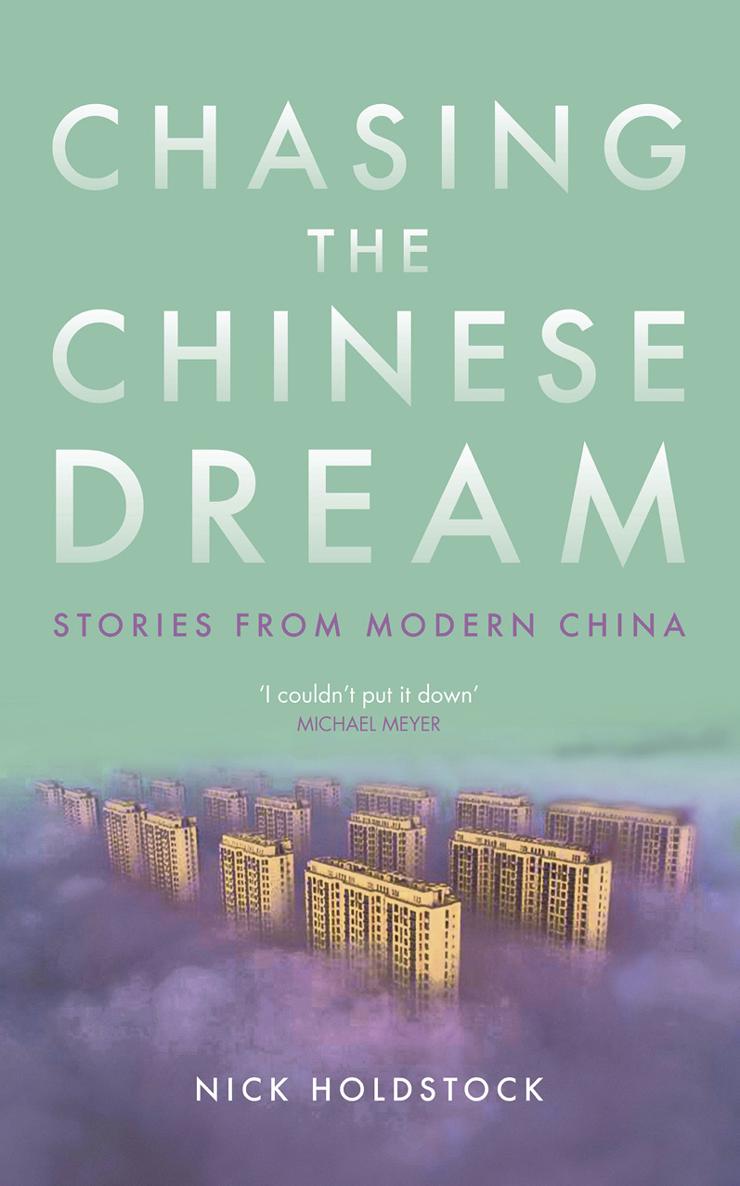

Nick Holdstock is a journalist and writer whose work has appeared in the London Review of Books , the Times Literary Supplement and the Guardian . He is the author of two books about Xinjiang, The Tree That Bleeds (2011) and Chinas Forgotten People: Xinjiang, Terror and the Chinese State (I.B.Tauris, 2015). His first novel, The Casualties , was published in 2015. He lives in Edinburgh.

At last, a book about China that takes the long view, showing how the Chinese Dream is playing out for a fascinating cast of characters that author Nick Holdstock has known for years. He writes with great warmth and deep empathy, capturing the realities of everyday life in places that foreign and Chinese correspondents pass by. I couldnt put it down.

Michael Meyer , author of

In Manchuria and The Last Days of Old Beijing

First published in 2017 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2017 Nick Holdstock

The right of Nick Holdstock to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

ISBN: 978 1 78453 373 1

eISBN: 978 1 78672 220 1

ePDF: 978 1 78673 220 0

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Text design, typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London

Contents

- Map of Provinces and Regions in the Peoples Republic of China

- Map of Hunan Province

Provinces and Regions in the Peoples Republic of China

Authors Note

Some of the names of my interviewees have been changed, either at their own request, or because it seemed prudent. At the time of writing, one US dollar was equivalent to 6.5 yuan.

The research that forms part of this book first appeared in the Dublin Review , the Los Angeles Review of Books , the Guardian and on the London Review of Books blog.

Introduction

Big City Dreams

For two years I taught English in a small city famous for clementines and murder. The clementines reputation was well deserved: they were at their sour best when green-skinned. As for the murders, if any took place, they were very discreet.

Shaoyang is an old city in the southern province of Hunan. It spreads along the junction of two rivers: the pale jade Shao River and the wider, brown Zi River. When I arrived in 1999 the citys population was just under half a million. From the city gate I could look over an expanse of old houses whose roofs of thick grey tiles overlapped like scales. In some respects the city hadnt changed much from the description offered by Dr George Pearson, a Christian missionary who lived in Shaoyang from 1920 to 1950:

Back then it was still a sleepy old place, with its stone wall built long before Christ. Every night its gates were shut to keep out bandits. Its streets were dark and very narrow with no room for cars or carts; there were stone steps everywhere, up and down. All traffic had to come and go carried by men. Passengers were carried in sedan chairs; all the shops were open to the street; there were no glass fronts.

Fifty years later the old city wall had gone, but at night many streets were still unlit. Most of the shops were in garage-like units that had roll-down shutters instead of doors. On the pavements people washed vegetables in plastic bowls, impaled eels on nails, and welded engine blocks. And everywhere the old stone steps still went up and down.

The teacher training college where I worked was on the edge of town. Behind the student dormitories there were just rice fields. English seemed to be regarded as a girls subject 90 per cent of my students were female. They were between 18 and 21, but seemed far younger. Their pencil cases and bags were covered with stickers of baby rabbits and kittens. They loved to sing songs. Any mention of boyfriends or kissing made them giggle and blush. When I asked my students what their parents did for a living, most said, My mother is a peasant, or, My father is a farmer.

At times the college felt like a cross between a prison camp and an orphanage. Students were fined if they missed the 6 a.m. morning exercise drill or were late to class. Much of their free time was spent listening to political speeches or picking up litter around campus. Their only possible response to this situation was to say mei ban fa , which means theres no choice. Its a phrase of resignation.

Most students were only at Shaoyang Teachers College because their scores on the gaokao , the National Higher Education Entrance Examination, were too low for them to get into a good university. Few of them wanted to be high-school teachers, because the pay was low and working conditions were poor: in the countryside, middle-school classes often had over 50 students, and there were few facilities except a blackboard and basic textbooks. The few students who expressed an interest in teaching usually explained their decision with platitudes like Teaching is the most glorious job under the sun. In more candid moments they spoke of pressure from their parents, who viewed teaching as a steady job.

On a wet day in February 2000, I was returning to Shaoyang after visiting friends in a nearby town for Chinese New Year. From the train window I looked out onto a landscape dissolved by rain. The fields were flooded, the hills a blur; no one was in sight. We passed clusters of houses built of faded brick whose doorways were framed by bright strips of red paper on which golden characters asked for luck, good health and double happiness.

As soon as the train pulled into Shaoyang it was clear something was wrong. Police officers stood in a long line on the platform. Behind them was a crowd of around five hundred people. As I got off the train the crowd began to shout and push. Then the police line dissolved and the crowd surged forward. All I could do was stand with my back to a pillar as people rushed to get on the train. The crush was worst around the train doors; some avoided this by climbing up the side of the carriage and clambering through the windows. One small man threw his sack in, then found he was too short to climb up. He had to be pulled up by two men inside, both of whom looked delighted to add another person to a carriage that was already full.

Whistles were blown as more people climbed through the windows. The platform was a mass of people pushing and shouting while dragging sacks and bags and boxes. I got out my camera and was able to take three or four pictures before a policeman shouted at me. I pretended not to hear, and turned and walked away. He caught up with me, pointed to the camera, and said, Give me that. I didnt argue. For the next ten seconds I had the petty pleasure of watching him struggle to find the lever that opened the back of the camera. Then, with a triumphant pop, the film was exposed.