NICK HOLDSTOCK spent three and a half years in China as a VSO teacher. Since returning he has had numerous articles published in publications such as the Edinburgh Review, n+1 and the LondonReview of Books. In March 2010 he went back to China to evaluate how the 2009 riots in Xinjiang have affected people's lives. He lives in Edinburgh and is currently studying for a PhD in English Liter ature. More information can be found at his website:

www.nickholdstock.com .

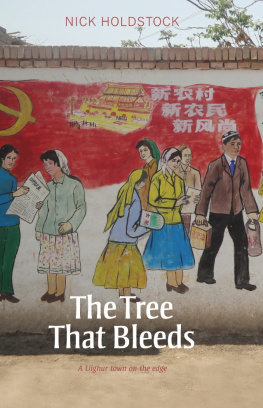

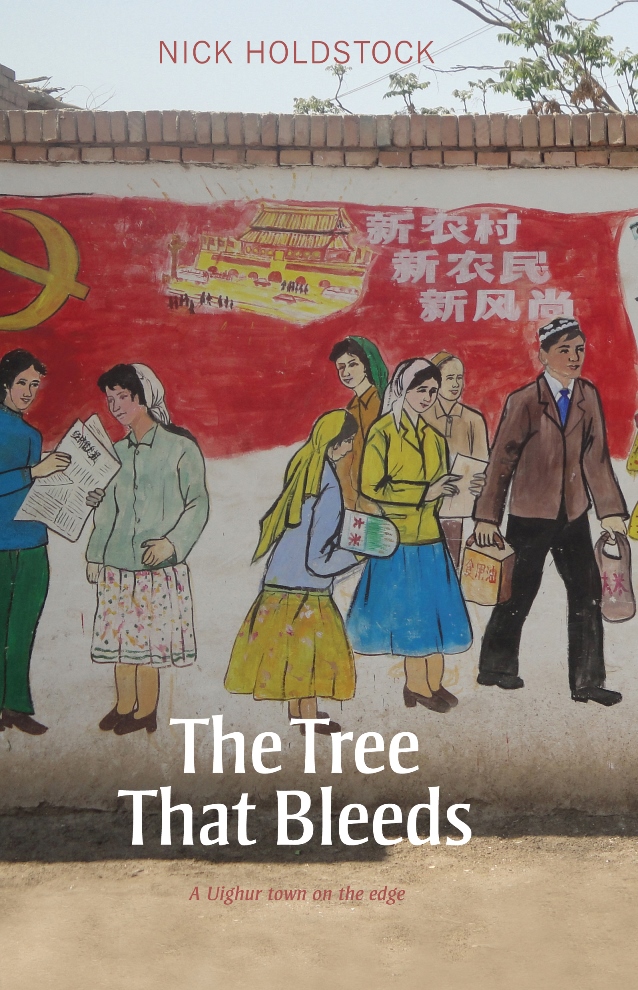

The Tree that Bleeds

A Uighur Town on the Edge

NICK HOLDSTOCK

Luath Press Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2011

eBook 2012

ISBN: 978-1-906817-64-0

ISBN: 978-1-909912-32-8

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Creative Scotland towards the publication of this book.

The author's right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Some sections of this book appeared in different form in Edinburgh Review, n+1 and the London Review of Books.

Nick Holdstock

For Magda Boreysza

Table of Contents

Major cities in Xinjiang

Acknowledgements

THERE ARE MANY people to thank, firstly Jennie Renton for suggesting I approach my publisher. I am also grateful to the Scottish Arts Council for helping fund my trip to Xinjiang in 2010. I would also like to thank John Gittings, former East Asia correspondent of TheGuardian, for his very helpful and encouraging feedback on an early draft of the manuscript.

Thanks to the following for giving advice, rooms to write in, hands to hold, a slap in the face when required: Ryan van Winkle, Benjamin Morris, Dan Gorman, Yasmin Fedda, Duncan Macgregor, Louise Milne and William Watson.

Thank you Mum and Dad.

I WAS LOOKING at the dome of a mosque when I heard the soldiers. The bark of their shouts, the stamp of their feet. I turned and saw rifles, black body armour, a line of blank faces. We were on Erdao qiao, a busy shopping street in Urumqi, where a moment before the main concerns had been the prices of trousers and shirts. But the crowd did not scatter in fear at the sight of these armed men. They parted in a calm, unhurried manner, as if this were a routine sight, almost beneath notice. For a moment the street was quiet but for the soldiers' marching chant. As soon as they passed, the sales men lifted their cries; haggling resumed. But there were more soldiers on the other side of the street, another black crocodile marching through. Policemen stood in twos and threes every hundred metres, outside a bank, a kebab stall, in front of the pedestrian subway. A riot van drove up and stopped at the intersection.

Although this display of force was disconcerting, it wasn't a surprise: nine months before, on 5 July 2009, this street had seen some of the worst violence in China since the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. Urumqi is the capital of Xinjiang, China's largest province. There has been a long history of unrest in the region, between Uighurs (Turkic-speaking Muslims who account for about half the region's 23 million people) and Han Chinese (the ethnic majority in China). The events of July 2009 marked an escalation in the conflict. During the afternoon of 5 July, around 300 Uighur students gathered in the centre of Urumqi. By late afternoon, the crowd had swelled to several thousand; by evening they had become violent. Official figures put the number of dead at 200, with hundreds more injured. News reports on state television showed footage of protesters beating and kicking people on the ground. Video shot by officials at the hospital the previous night showed patients with blood streaming down their heads. Two lay on the fruit barrow that friends had used to transport them. A four-yearold boy lay on a trolley, dazed by his head injury and his pregnant mother's disappearance. He had been clinging to her hand when a bullet hit her.

By the following morning the streets were under the tight control of thousands of riot officers and paramilitary police, who patrolled the main bazaar armed with batons, bamboo poles and slingshots. Burnt cars and shops still smouldered. The streets were marked with blood and broken glass and the occasional odd shoe. Mobile phone services were said to be blocked and internet connections cut.

There were two main explanations for what had caused these riots. On the one hand, a government statement described the protests as 'a pre-empted, organized violent crime' that had been 'instigated and directed from abroad, and carried out by outlaws in the country'. Xinhua, the Chinese state news agency, reported that the unrest 'was masterminded by the World Uighur Congress' led by Rebiya Kadeer, a Uighur businesswoman jailed in China before being released into exile in the US. Wang Lequan, then leader of the Xinjiang Communist Party, said that the incident revealed 'the violent and terrorist nature of the separatist World Uighur Congress'. He said it had been 'a profound lesson in blood'.

He went on to claim that the aim of the protests had been to cause as much destruction and chaos as possible. Although he mentioned a recent protest in the distant southern province of Guangdong, he dismissed this as a potential cause.

But according to the WUC, this incident was the real cause of the protest. They claimed that the clash in Guangdong province was sparked by a man who posted a message on a website claiming six Uighur boys had 'raped two innocent girls'. This false claim was said to have incited a crowd to murder several Uighur migrant workers at a factory in the area. Rebiya Kadeer claimed that the 'authorities' failure to take any meaningful action to punish the [Han] Chinese mob for the brutal murder of Uighurs' was the real cause of the protest.

The WUC's version of the events of 5 July was that several thousand Uighur youths, mostly university students, had peacefully gathered to express their unhappiness with the authorities' handling of the killings in Guangdong. They claimed that the police had responded with tear gas, automatic rifles and armoured vehicles. They alleged that during the crackdown some were shot or beaten to death by Chinese police or even crushed by armoured vehicles.

The WUC also reported widespread violence in the wake of the protests. Their website claimed that Chinese civilians, using clubs, bars, knives and machetes, were killing Uighurs throughout the province: 'they are storming the university dormitories, Uighur residential homes, workplaces and organizations, and massacring children, women and elderly'. They published a list of atrocities 'a Uighur woman who was carrying a baby in her arms was mutilated along with her infant baby over one thousand ethnic Han Chinese armed with knives and machetes marched into Xinjiang Medical University and engaged in a mass killing of the Uighurs two Uighur female students were beheaded; their heads were placed on a stake on the middle of the street' none of which could be confirmed. This post was later removed.