Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

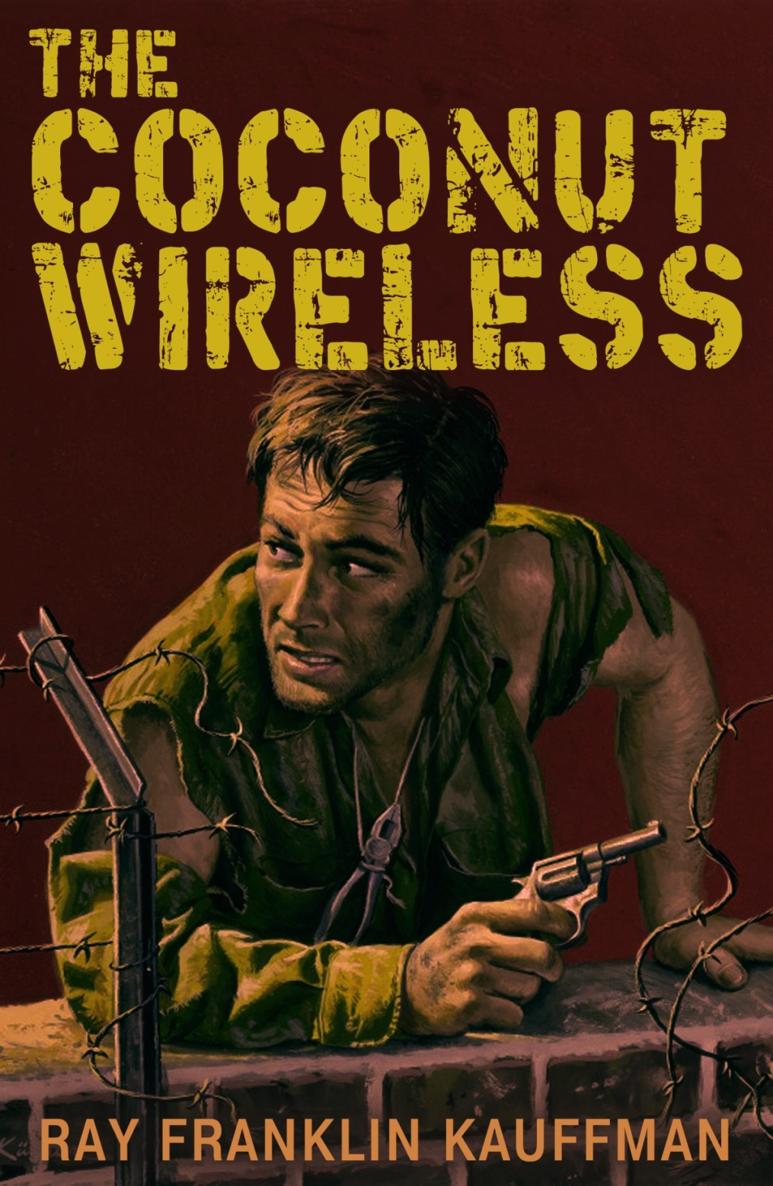

THE COCONUT WIRELESS

RAY FRANKLIN KAUFFMAN

1

LIGHTNING stabbed crookedly at the jungle, thunder crashed over the peninsula. It was the season of squalls heralding the northeast monsoon, and already a chill breeze smelling of the wet land was felt aboard the prau, where an old Malay crouching aft blew on the coals in a clay cooking pot, the dull red glow momentarily lighting the high cheekbones and the wrinkled depressions of a toothless face.

A searchlight from a Japanese patrol vessel ghosting along with the tide swept the fleet of fishing junks and praus and sampans huddled in the lee of the land. Then the light carefully examined the shore line; the tide was up and the low tangle of mangrove branches touched the water. The old man in a gesture of dislike ejected a stream of betelnut juice after the departing patrol vessel. For with the coming of the Japanese had come countless regulations to govern the life of the Orang Laut (sea gypsies) and the fisherfolk.

His rice cooked, he took the pot off the coals to cool and then turned his back on the rising wind and thunder and faced west toward Mecca. The island of Penang rose in black silhouette above the dimly lit town. He bowed low and prayed to Allah that the war would soon be ended and that all foreigners and unbelievers with their papers, documents and rubber stamps would leave his land in peace.

Absorbed in prayer and reverie, he did not see a hand rise out of the sea and clutch the gunwale of the prau, the two eyes under a mop of dripping hair. He did not hear the heavy breathing or the thud of knees on the deckonly the thunder, and the wind beating the frayed halyards against the mast. A few drops of rain drummed on the dry thatched shelter amidship. The old man straightened. The searchlight from the Jap patrol vessel was coming back up the channel, picking out each cleft in the wall of mangrove. Then he felt a motion at his back. He half turned. A hand like a steel claw closed over his mouth, stifling his scream of terror. His shoulders writhed involuntarily from the sharp prick of a kris.

Then a quiet voice said, Silent, old one.

The old man relaxed and stared dumbfounded at the white skin of a tall naked man with a dripping wad of clothing tied around his neck.

Lekas! Quick! Get into your small boat, said the white man, pointing to the little log canoe dancing astern.

Tuan, this is my only living. Without my boat my family will starve...Look! He pointed to the light. Now we will all be killed.

But the white man, dumb to his protests, crawled forward and cut the anchor line. The prau swung broadside to the wind. He stepped over to the mast, felt the halyard and hauled the sail aloft. Terrified, the old man jumped in the canoe and cast loose. The light cloth whipped out to leeward. Then the sail sheeted home, bellied, and the prau raced before the squall like a mad thing. The searchlight swept again the fleet of fishing boats. Then heaven descended on earth and blotted out all visibility. The old man, bending his head to the storm, paddled shoreward. In one blinding flash of lightning he saw only the sail of his prau flying off to the westward.

In the morning he went dutifully to the customs office on the jetty at Penang to see the Kempei (Japanese Military Police) to report the theft of his boat. With straw hat in hand he waited patiently for his turn to enter the sentry-posted building. Suddenly a young Chinese fell headlong out of the doorway. His face was bloody and swollen. He lay in a shallow pool of rain water from last nights storm, writhing and shrieking in pain. A Japanese soldier followed and kicked the Chinese in the stomach, in the crotch and in the face until the body lay quite still. The old man shuffled quietly away. He would not report the theft of his boat after all.

But around the charcoal pots on his neighbors prau he told his tale, and the tale was retold from boat to boat up and down Malacca Straits from Phuket to Singapore until it became a new legend heralding the approach of the northeast monsoon: Orang orang, beware when the shadow of your mast first falls to the north. For then the storms roll down from the mountains and a white ghost comes out of the sea who speaks the common language with the tongue of man, but in his veins runs only salt water and his eyes are made of phosphorescence. Look always to windward and do not pray facing Mecca after the sun is gone. For the ghost comes with the wind and will spirit your boat away.

On Ceylon the sea broke furiously on the off-lying rocks, then surged across the shallows in a welter of foam to pile up on the beach inside the rock-choked entrance of the lagoon at Nelaveli just north of Trincomalee. Tamil fishermen, black from the sun, strained backwards against the great net pursed out in the clear green water. Their monotonous, cadenced chant, as step by step they worked the net up the beach, stopped suddenly when the headman, standing high on the beach in the shade of the pandanus, cried out, pointing seaward. A strange craft under a low, square-cut sail was heading straight for shore. She cleared the outer reef in a smother of white water, broached to, miraculously stood upright and then sailed straight for the sharp red rocks at the lagoons entrance. The fishermen, shouting, beckoned the stranger toward safety. In the first line of break the vessel broached again and a second later smashed against the rocks. The receding wave sucked her back seaward, and then another sea drove her head on between two rocks, where the mast snapped off at the deck and went over forward. The split sail fluttered like the wings of a wounded bat and then was stilled by the weight of the water. Her buoyancy gone, the wreck lay inert. There was no sign of life aboard. The fishermen approached cautiously. Then a sea washing over the stern carried away the coconut-thatched shelter and revealed the body of a man face downward on deck across the long tiller handle.