A LSO B Y

A NDREA M ARCOLONGO

The Ingenious Language

STARTING FROM

SCRATCH

To My Country, Italy

T HE L ESSON OF A ENEAS

Learn valor from me, my son, and true toil;

fortune from others.

(Aeneid, 12.435-436)

I have never heard anyone, when asked to name their favorite hero, answer Aeneas. And thats coming from someone who lived for a time in Rome.

If people have an impression of Aeneas, even a faint one, which is not a given, since more often than not people have nothing to say about himthey greet him with total indifferenceits that hes a cad. Fates errand boy, with a mushy spine. Someone tossed about by the gods who stumbles upon an empire almost by accident. Someone who runs for the hills whenever something really epic happens to him, like being seduced by an irresistible queen from Carthage eager to offer him her kingdom. After all, what kind of hero wanders around the Mediterranean with his hands clasped and can only psych himself up with pietas?

I have long asked myself why the character of Aeneas has had to endure such harsh judgments, judgments that would have us believe that the Aeneid is a story for the faint of heart. It only recently dawned on me that the mix of discomfort and irritation that people feel when reading Virgils epicor at the mere mention of itis connected not to the shabby figure of Aeneas so much as to the historical moment in which one reads the Aeneid. And to my recently above, I feel compelled to add unfortunately.

The Aeneid is not an epic for times of peace. Its verses are not suited to smooth sailing. When all is well, the Aeneid bores people to deathand lucky are those who, for centuries, have had the luxury of yawning at its hexameters. Woe is us, for the song of the Aeneid is meant for moments when people desperately need to wrap their heads around an after that is shockingly different from the before theyd always known. In the parlance of forecasters: The Aeneid is warmly recommended reading for days when youre in the eye of a storm without an umbrella. On sunny days, it serves little to no purpose.

Thats how things have stood from the start, after all. From before the start, actually. Virgil was writing about Aeneass travails while he himself was treading water during that historic age when the Roman Empire was rearing its head over the rubble of the Republic.

The Aeneid came back in vogue in the Middle Ages, when no one knew which way to turn or whose side to take or what language to speak after the fall of the Roman Empire in the West, and Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus with a chuck under the chin. It did so again in Dantes Florence, a city divided like cells into Guelphs and Ghibellines, Blacks and Whites, and would have to wait a century for the arrival of Lorenzo the Magnificent. People also turned to Virgil at the turn of the twentieth century, when the world was suspended between euphoria over the dawn of modernity and terror upon quickly discovering modernitys side effects: Being new is always a terrible burden.

That is to say nothing of the birth of Christ, the great before-and-after event that divided human history into two distinct parts. For a long time, humanity tried to find evidence of the new Christian era in Virgils verses, twisting them out of shape in order to substantiate something that, by its divine nature, could not possibly be substantiatedand that unsettled people for its lack of precedence.

Thats natural. In times of peace and prosperity we ask Homer to teach us about life. We understandably demand to dwell in something other than dead calm. Our thymos, as the Greek philosophers called it, otherwise known as lan, our hunger for life, gallops ahead at breathtaking speedand if we really are guided, deep down, by the winged charioteer that Plato describes in the Phaedrus, it is clearly the black horse of passion now pulling our chariot, and the white horse of reason is perfectly happy to bide its time.

Yet whenever there is historic upheaval, we set the Iliad and Odyssey down on the nightstand and snatch the Aeneid off our shelves. All we feel is fear and the desperate need to surviveour invisible charioteer no longer worries about where to go but how to get the wagon back on its wheels after it has toppled over and crippled both horses.

Why didnt anyone tell us this about the Aeneid? Obviously, in times of war, nobody is assembling fancy critical editions. And in times of peace people just want to move on, to forget.

* * *

Sitting on the banks, waiting for our enemies bodies to float by, we are well within our rights to indulge in the luxury of choosing to side with Hector or Achilles, or of browsing the menu of Ulysses adventures, and his women. But when we have to fight to ensure that the body drifting downstream is not our own, that is when Aeneas is called for. So why, even as we recognize how much we need him, can we not help but detest him, at least a little? Because Virgils hero does nothing to comfort us. On the contrary. He has the nerve to provoke us.

The Aeneid opens with Troy in ruinsand does everything to demolish all we think it is we want and feel while were surrounded by ruins ourselves. Fear, for starters. Aeneas suffers, his every action is imbued with pain, yet he seems immune to anguish. Where we remainunderstandablypetrified, he presses on and never stops marching forward.

As we shall see, he cries a lot. Yet he always answers fear with courage. He doesnt shirk his duty to look spine-tingling reality in the face. He doesnt hesitate to name what moments ago no one had a name for or confront phenomena no one had ever experienced before.

Aeneas thinks, takes stock, struggles to make sense of things. With the rigor of rationality, he creates order out of chaos. Thats exactly why Aeneas seems so detestable at first. Like us, he doesnt know what to do, yet still he does it. Like us, he doesnt know where to begin, but when in doubt he begins. Hes irritating, truebecause he keeps reminding us that it is fundamental to go on.

Whats more, Aeneas doesnt correspond to our idea of a strongman (criticize him all you like, but the inverse of Aeneas is a dictator). He is anything but the proverbial man at the top, in whose hands the weight of founding a nation is placed so that we may wash our own of the endeavor.

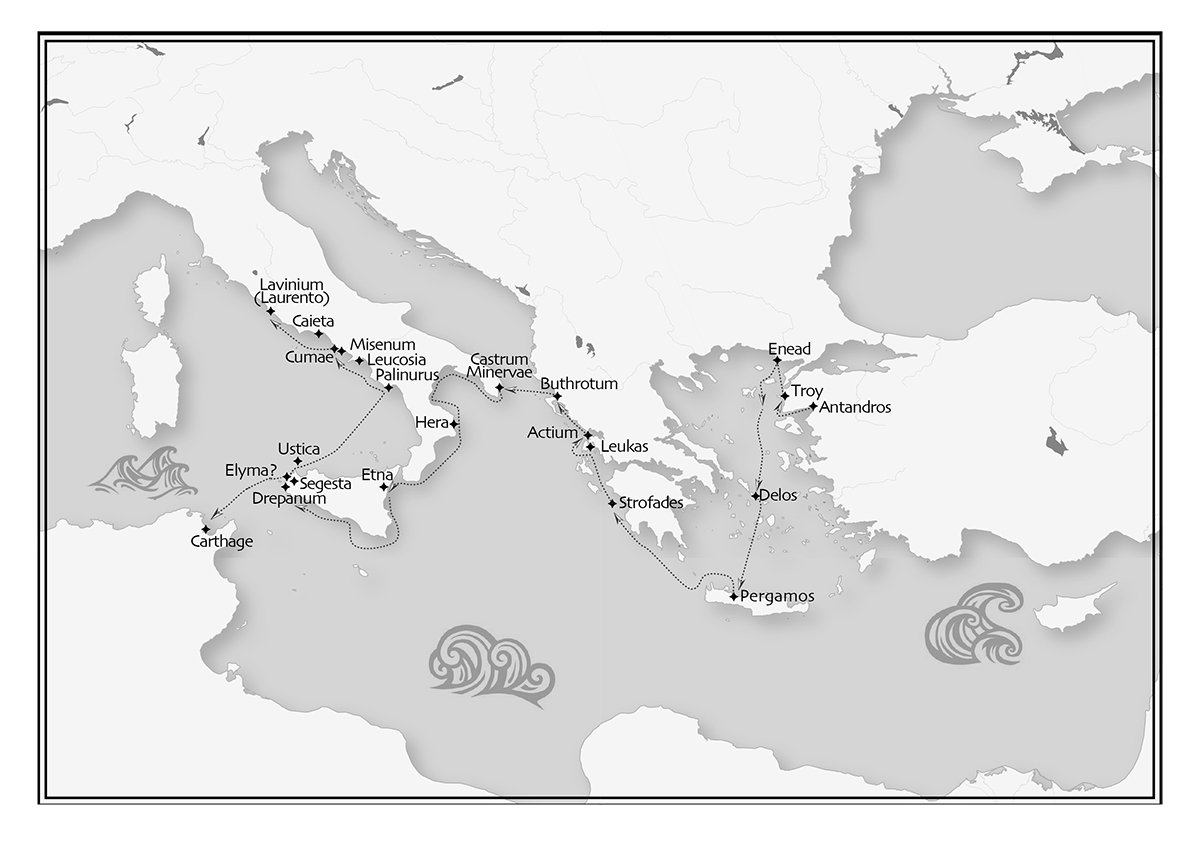

Aeneas commands nothing if not a handful of fellow neer-do-wells. Hes not even that tough: All he does is fumble about on his voyage from Troy to Latium. And he doesnt embark on his voyage alone; he travels with his father and son in tow and the Penates in his pocket. If only he had a weapon or a magic potion or a superpower that distinguished him from ordinary survivors like ussomething that kept us from having to conclude that, if he can do it, so can we.

Being Aeneas means one thing: answering destruction with reconstruction. Thats the lesson of Aeneas.

1

H OW T HIS B OOK C AME TO B E

Everything holds on

everything goes on

everything subsists

everything resists

G IORGIO M ANGANELLI , from Appendix IIA, Poems

The truth is I didnt want to write this book. I would have preferred to go on being confused and ambivalent about Virgil, unsure whether I liked the epic or whether it bored me stiff. Maybe I would have preferred to go on opening the Aeneid out of curiosity every three or four years, the way I had since my school daysjotting down in my notebooks what I didnt get about the poem and postponing the obligation to understand it.