A Country in the Mind

A C ountry in the M ind

Wallace Stegner, Bernard DeVoto,

JOHN L. THOMAS History, and the American Land

A volume in the series Culture/Society/Politics, edited by David Nasaw.

First published in 2000 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2000 by Routledge

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thomas, John L.

A country in the mind: Wallace Stegner, Bernard DeVoto, history, and the American land / John L. Thomas,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0415927811

1. DeVoto, Bernard Augustine, 18971955Criticism and interpretation. 2. Literature and historyWest (U.S.)History20th century. 3. Stegner, Wallace Earle, 1909Criticism and interpretation. 4. DeVoto, Bernard Augustine, 18971955Friends and associates. 5. Stegner, Wallace Earle, 1909Friends and associates. 6. American fiction20th centuryHistory and criticism. 7. American fictionWest (U.S.)History and criticism. 8. Conservation of natural resources in literature. 9. Wilderness areas in literature. 10. West (U.S.)Historiography. 11. West (U.S.)In literature. 12. Landscape in literature. 13. Land use in literature. 14. CommonsWest (U.S.) I. Title.

PS3507.E867 Z94 2000

813.52093278--dc21

00-036631

Title page: An alcove in the Red Wall. (From The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons, J. W. Powell, 1895.)

For Blake and Chandler

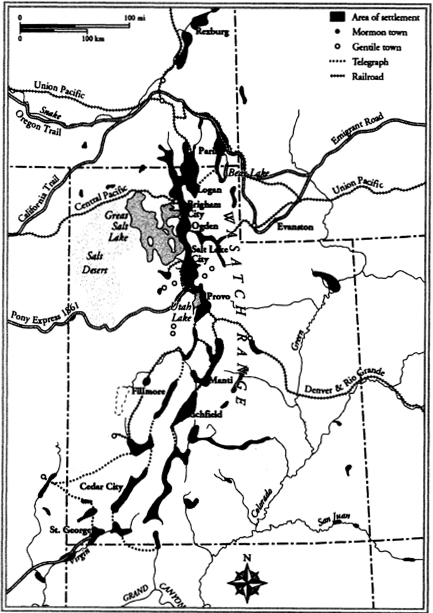

Mormonland, 1890.

Contents

Prologue

Overleaf: Kanab Canyon, in the Red Wall Limestone. (From The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons, J. W. Powell, 1895.)

I have spent a good part of my intellectual life tracking what I have called Alternative America across time and space from antebellum communitarian experiments in New England and the Burnt-Over District of New York to postCivil War theorists and reformers in Illinois coal mines and California wheatfields and on to twentieth-century plans for migrations out of metropolises into a producerist countryside. The phrase itself is elastic, not to say elusive, bending and fitting itself to varying developmental winds blowing across the country over the years. Whatever political concessions the idea of an Alternative America has been forced to make to voters and politicians, the vision of another waya middle road between a profit-driven market economy on the one side and a repressive collectivism on the otherhas enjoyed a long if not always happy life.

In the years before the Civil War the advocates of a cooperative alternative to Jacksonian scrambles for spoils opted out of the rat race, as they thought it, and formed a number of voluntary communities as a means of educating their fellow citizens and converting them to a better life. Not many of these experiments survived competition with an aggressive entrepreneurial capitalism, and those that did were apt to have been gathered Christian communitiesShaker, Mormon, Oneidanwilling to forgo material wealth for spiritual health. The more secular communities, like that at Roxburys Brook Farm or those at nearby Fruitlands and Hopedale, collapsed under the weight of constitutional baggage piled on by members struggling to find the exact balance between collective need and individual freedom. Yet taken together even in their failure, these communitarian experiments signified a profound unease with rampant developmental capitalism and a conviction that individual aspirations and social energies could be peacefully harmonized by the simple application of social mathematics.

Despite the shortcomings of their social analysis and their various Utopian arrangements, the communitarians left an ethical legacy for postCivil War reformers equally disgusted with the rapacity of Gilded Age businessmen and their political pals. The principal spokesmen for an Alternative America in the later years of the nineteenth century were the reform theorists-turned-activists Henry George, Edward Bellamy, and Henry Demarest Lloyd. Georges balanced utopia was the creation of a single tax, his magic device for preventing the monopolizing of land and ensuring the stability of the nations small communities. Bellamy envisioned a cooperative mass society organized as an ethical army practicing a religion of solidarity by employing the techniques of mass production and distribution to provide complete equality. Lloyd in his turn offered a vision of an Americanized Fabian socialism that would harness the power of the federal government to secure a decent life for all Americans. It is worth noting that all three men were writers and journalists critical of Gilded Age excess who became vigorous reformers and turned to politics as a means of realizing their ethical vision. Aspects of the thought of all three men appeared in Populism as it emerged out of the Farmers Alliance in the early 1890s, in particular its call for the assertion of national authority in behalf of beleaguered little people working the land.

Just as the late nineteenth-century reformers borrowed some of their ethical precepts from their antebellum predecessors, so they themselves left a legacy of their own to twentieth-century recipients. Among them: Upton Sinclair with his moderate socialism and End Poverty in California campaign; Benton MacKaye with his communally constructed Appalachian Trail; Lewis Mumford with his call for a fourth migration out of the American metropolis into the countryside. These and a whole host of independent intellectuals in the first half of the twentieth century helped themselves to fragments of the adversarial tradition which they pieced together, adapted, and modified to suit their various purposes. Common to all their efforts was a vision of a democratic participatory ethic as the source of a renewed civic spirit. Here in barest outline is an alternative tradition undergoing all kinds of permutations over two centuries but retaining throughout the vision of a civic entity situated in a middle ground between capitalist consolidation and control and coercive collective management.

Now there appear two other recruits to the ideal of a national commons owned and cared for by all the citizenryBernard DeVoto and his friend Wallace Stegner. At once artists and reformers, novelists and historians, they shared a recognition of the increasingly dire need to save wilderness, protect parks and forests, and prevent further degradation of the West, which was proceeding rapidly with the consolidation of corporate capitalism. Both men railed against the spoilers and their apologists, and called for an expanded role for the federal government even as they criticized the shortcomings and inefficiencies of its bureaus and agencies. Friends, occasional colleagues, warm admirers of each others work, they offered a vision of citizen stewardship over the American land with directives coming from Washington and implementation supplied by enlightened local citizens adhering to a shared land ethic. In other words, an environmental alternative to the wastage and spoliation practiced by corporate giants.