Table of Contents

For M.P.S., in gratitude for more than

a half century of love and friendship,

and to the friends we were both blessed by.

I could give all to Time exceptexcept

What I myself have held. But why declare

The things forbidden that while the Customs slept

I have crossed to Safety with? For I am There

And what I would not part with I have kept.

ROBERT FROST

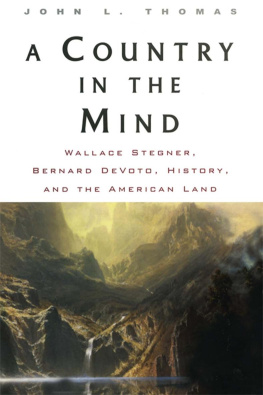

WALLACE STEGNER

Wallace Earle Stegner, the award-winning novelist, biographer, historian, essayist, critic, environmentalist, and teacher who pursued the truths that lay behind the mythology of the American West, was born in Lake Mills, Iowa, on February 18, 1909. He grew up in countless boom-and-bust towns all over the West as his father shuttled the family through Saskatchewan, North Dakota, Washington, Montana, and Nevada before finally settling in Salt Lake City in 1921. Stegner entered the University of Utah in 1925 and started writing fiction while a graduate student at the University of Iowa in the 1930s. He began his teaching career at the University of Utah and later taught at both the University of Wisconsin and Harvard. From 1946 until his retirement in 1971 Stegner headed the prestigious creative writing program at Stanford, which has had a profound effect upon contemporary American fiction. Twice a Guggenheim Fellow, he was also a Senior Fellow of the National Institute for the Humanities as well as a member of the National Institute and Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Stegner made an auspicious literary debut in 1937 with Remembering Laughter, a rueful tale about an adulterous triangle in Iowa farm country that evoked comparisons with Ethan Frome. His next three novels The Potters House (1938), On a Darkling Plain (1940), and Fire and Ice (1941)disappointed reviewers. But he enjoyed widespread popular and critical success with The Big Rock CandyMountain (1943), a semiautobiographical chronicle of a nomadic family drifting through the West in search of an easy life that is always just out of reach. His other novels of this period include Second Growth (1947), a story about the conflict between puritanical values and modern morality in a New England town, and ThePreacher and the Slave (1950), a brilliantly imagined portrait of Joseph Hillstrom, the legendary outlaw and labor organizer who became a martyr following his execution for murder in 1915. After abandoning long fiction for more than a decade Stegner returned to novel writing with A Shooting Star (1961), the bestselling story of one womans hard-won triumphs over the irrational drives that have brought her to the edge of doom, and All the Little Live Things (1967), the tale of a New York literary agent who retires to California only to be engulfed by the chaos of the 1960s.

Meanwhile Stegner gained a whole new readership with his probing works of nonfiction. In Mormon Country (1941) and TheGathering of Zion: The Story of the Mormon Trail (1964) he dramatically recounted the epic history of the Mormons. In Beyond the Hundredth Meridian (1954), a biography of naturalist and explorer John Wesley Powell, he presented a fascinating look at the old American West as seen through the eyes of the man who prophetically warned against the dangers of settling it. And in Wolf Willow (1962), a memoir of his boyhood in southern Saskatchewan, he offered an enduring portrait of a pioneer community existing on the verge of the modern world. Saturday Review judged Beyond the Hundredth Meridian and Wolf Willow two of the most important Western books of the decade . Both are so to speak geo-history, intensified, sharpened, made viable and useful by poetic insights and a keen intelligence. Stegners enchantment with the West is reflected too in the essays collected in The Sound of Mountain Water (1969) and One Wayto Spell Man (1982), two volumes that also voice his frontline views on wilderness conservation. As Wendell Berry observed: Stegner is a new kind of American writer, one who not only writes about his region, but also does his best to protect it from its would-be exploiters and destroyers.

Stegner was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Angle of Repose, which came out in 1971. Angle of Repose is a long, intricate, deeply rewarding novel, wrote William Abrahams in the Atlantic Monthly. [It] is neither the predictable historical-regional Western epic, nor the equally predictable four-decker family saga, the Forsytes in California, so to speak . For all [its] breadth and sweep, Angle ofRepose achieves an effect of intimacy, hence of immediacy, and, though much of the material is historical, an effect of discovery also, of experience newly minted rather than a pageantlike recreation . Wallace Stegner has written a superb novel, with an amplitude of scale and richness of detail altogether uncommon in contemporary fiction.

Angle of Repose is a novel about Time, as much as anything about people who live through time, who believe in both a past and a future, remarked Stegner. It has something to say about the relations of a man with his ancestors and his descendants. It is also a novel about cultural transplantation. It sets one mans impulse to build and create in the West against his cultivated wifes yearning for the cultural opportunities she left in the East. Through the eyes of their grandson (a man living today) it appraises the conflict of openness and change with the Victorian pattern of ingrained responsibilities and reticences; and in the entangled emotional life of the narrator it finds a parallel for the emotional lesions in the lives of the grandparents. It finds, that is, the present in the past and the past in the present; and in the activities of a very young (and very modern) secretary-assistant it reveals how even the most rebellious crusades of our time follow paths that our great-grandfathers feet beat dusty.

Stegner enjoyed great critical acclaim for his next work, The Uneasy Chair (1974), a full-scale biography of Bernard DeVoto, the historian, novelist, and ferociously funny critic of American society. [This] book is full of dramatic episodes and offers, from a special point of view, a battlefield panorama of the literary world from 1920 to 1955, said Malcolm Cowley. [Stegner] is an ideal biographer for DeVoto. Their careers sometimes crossed . Both were brought up in Utah . And both, as Stegner says, were novelists by intention, teachers by necessity, and historians by the sheer compulsion of the region that shaped us. Time agreed: The UneasyChair consistently goes beyond the limits of its subject to illuminate what it meant to be a writer in the America of the 30s, 40s, and 50s.

In 1977 Stegner won a National Book Award for The SpectatorBird (1976), in which he again depicted literary agent Joe Allston, the protagonist of All the Little Live Things. Likewise in Recapitulation (1979) Stegner resurrected Bruce Mason, a character from The BigRock Candy Mountain, to assess the course his life has taken. This is Stegners The Sound and the Fury, said the novelists biographer Jackson Benson. Like the Faulkner novel, Recapitulation is a book about time and its multiplicity of meanings in human experience, about the history of a family in its decline. Stegners last novel, Crossing to Safety (1987), traces the turbulent, lifelong friendship of two college professors and their wives. A superb book, said

Next page