Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

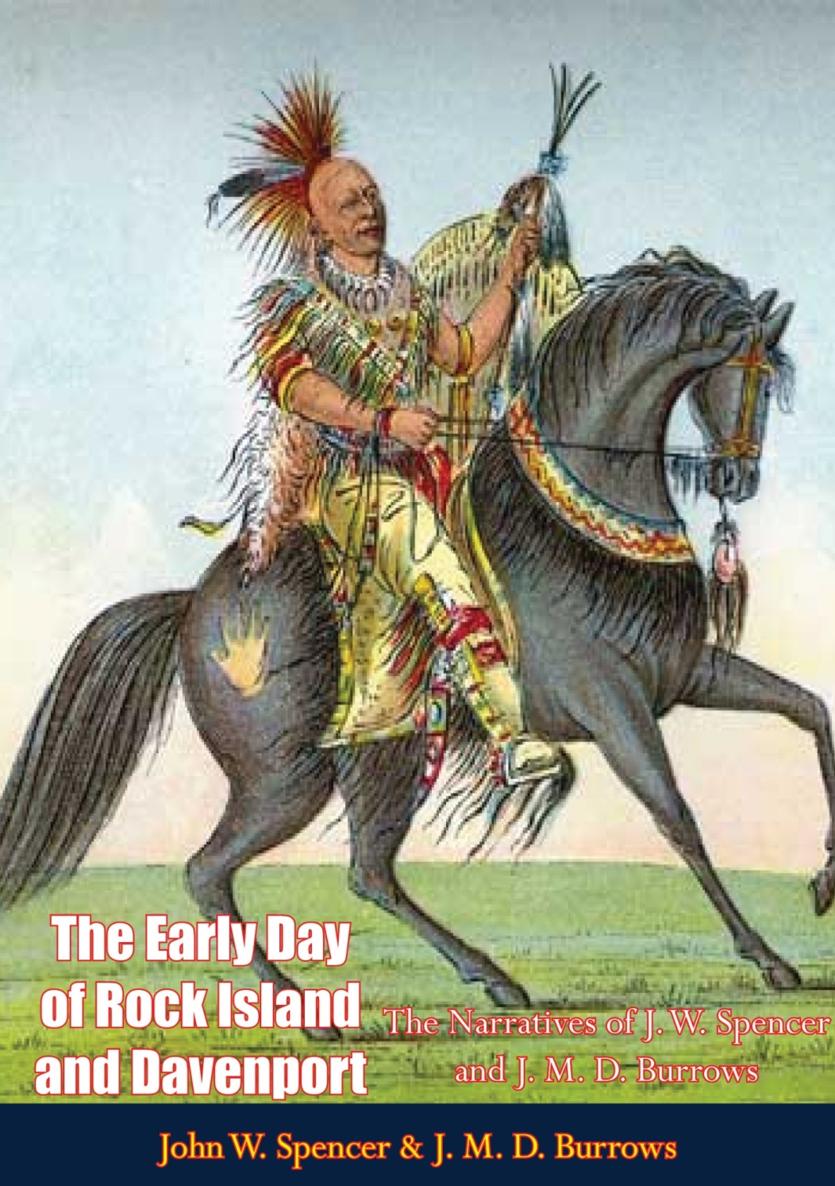

The Early Day of Rock Island and Davenport

The Narratives of J. W. SPENCER AND J. M. D. BURROWS

EDITED BY

MILO MILTON QUAIFE

SECRETARY OF THE BURTON HISTORICAL COLLECTION

Table of Contents

Contents

Table of Contents

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Publishers Preface

IN times of war it is difficult to determine how many and which of our habitual indulgences should be sacrificed on the altar of patriotism. As one grows older, habits become more and more fixed, and the habit of sending each year another volume of The Lakeside Classics to the friends and patrons of The Press has become so firmly established as part of the years operation that the Management is loath to give it up.

Fortunately, Congress in its omniscience eliminated books from its price control bill, inferring that the printing of books is privileged. At least such is the interpretation of the Publishers, who have decided to maintain the continuity of the series by issuing this, its fortieth volume.

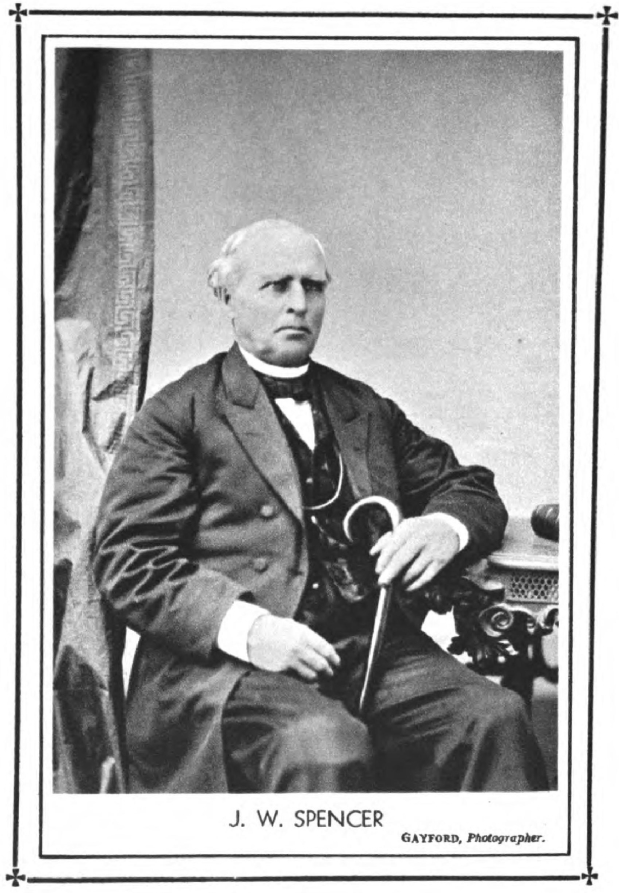

For the subject matter we have returned to the early days of Illinois and Iowa and are reprinting the reminiscences of two early settlers, Messrs. J. W. Spencer and J. N. D. Burroughs. Spencer migrated in 1820 from Vermont to that part of Illinois of which Rock Island is the center. More than half his narrative concerns the Blackhawk War in which he served, part of the time as First Lieutenant of the Rock Island Rangers. It tells the story of the war from the viewpoint of the white settler and supplements Blackhawks autobiography which was published in this series in 1916.

Burroughs moved from Cincinnati to Davenport in 1839 when Davenport was a small village. Like all other pioneers, he bought land and started farming, but he soon shifted to merchandising. From his cousin, who was a member of a firm of wholesale grocers in Cincinnati, he obtained on credit a small stock of goods and opened a store in Davenport. He showed business ability, and the store was an immediate success.

His narrative introduces a new character into this series, a pioneer merchant, and his story of trading with the settlers for over twenty years pictures the important role a merchant-trader played in pioneer life, not only making available to the farmers their necessities in the line of store goods, but at the same time opening for them a ready market for their products. It also pictures the complications and disasters of the use of the common currency of the timewildcat money.

We hope that these reminiscences of Spencer and Burroughs during their pioneer days in Illinois and Iowa will give our friends and patrons during the Christmas holiday season a little respite from the war news so prolixly amplified by reporters, correspondents and radio commentators.

We remain,

Respectfully yours,

THE PUBLISHERS.

Christmas 1942

The Early Day of Rock Island and Davenport

Historical Introduction

IF another Columbus were to visit North America and survey the entire Continent in search of a promising site for a colony there would be no cause for surprise if his choice should fall upon the entrancing locality at the mouth of Rock River, where the cities of Moline, Rock Island, and Davenport now cluster. From this center, for hundreds of miles in every direction stretches an agricultural Eden. Here is the heart of Cornland, before whose annual output of wealth the produce of the storied Nile pales to insignificance. Here, too, is an industrial development the equal of any in the world. The Tri-Cities themselves are hives of industry, from whose factories the machinery of both war and peace stream endlessly; while within easy reach by rail and highway lie many of Americas busiest cities.

Yet the entire fabric of white civilization in the tributary region is the fruit of hardly more than a century of time and toil. Chicago, the greatest city of interior America, celebrated her Century of Progress only a decade ago. The government agents who negotiated the Indian treaty of 1821 found not a single house between Peoria and Chicago. In 1823 a government exploring expedition was delayed for days at Chicago awaiting a guide who could conduct it across the wilderness to Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. The first steamboats that ever visited Chicago came in 1832, bearing the soldiers who were to conclude the Black Hawk War, and on arriving they found no port or harbor, for neither then existed.

The westward-marching settler was now close at hand, however, and his rapid advance over the Upper Mississippi Valley is significantly registered in the organization of Wisconsin Territory in 1836, Iowa Territory in 1838, and Minnesota Territory in 1849, to be followed in each case by admission to statehood in a dozen years or less.

Although the settler came to subdue a wilderness, it was not a vacant land. For unrecorded ages the Red Man had occupied it, developing a Stone-age culture which made but slight use of the natural resources of the country and which knew nothing of material progress or change. The culture of the white man was utterly antipathetic to this, and when the two races came together the swift conquest and displacement of the red man by the white was inevitable. With variations of local detail the process was everywhere repeated as the settler moved westward across the Continent. Yet the Indian was a human being who genuinely loved his native land, and his conquest, however inevitable, involved much of grief and tragedy. At Rock Island the conflict was more than ordinarily dramatic. I loved my towns, my cornfields, and the home of my people said the fallen Black Hawk. I fought for it...I have looked upon the Mississippi since I was a child. I love the great river. I have dwelt upon its banks since I was an infant.

The old-age narratives which are reprinted in the pages that follow the present introduction record the experiences and reflect the ideals and opinions of two early white settlers at the mouth of Rock River. John W. Spencer, whose Reminiscences of Pioneer Life is presented first, was a native of Vermont who in early manhood migrated to Illinois in 1820. As an early white settler he shared in all of the developments which culminated in the Black Hawk War of 1832, and his narrative is in large degree an old-age recital of that struggle. It seems evident that when he came to write it he endeavored to fortify his memory by reference to certain narratives which were already in print, and his own story is a mixture of personal knowledge and recollections with information derived from the sources of information already mentioned. Although the author achieved success in life, and bore the title of Judge, his story necessarily exhibits some of the defects which are inherent in old-age narratives of the type to which it belongs. It sheds interesting light upon the period it covers, telling us as much, perhaps, about the pioneer Illinois settler as it does about the red man whom he displaced.