IMAGES

of America

ROCK ISLAND

ARSENAL

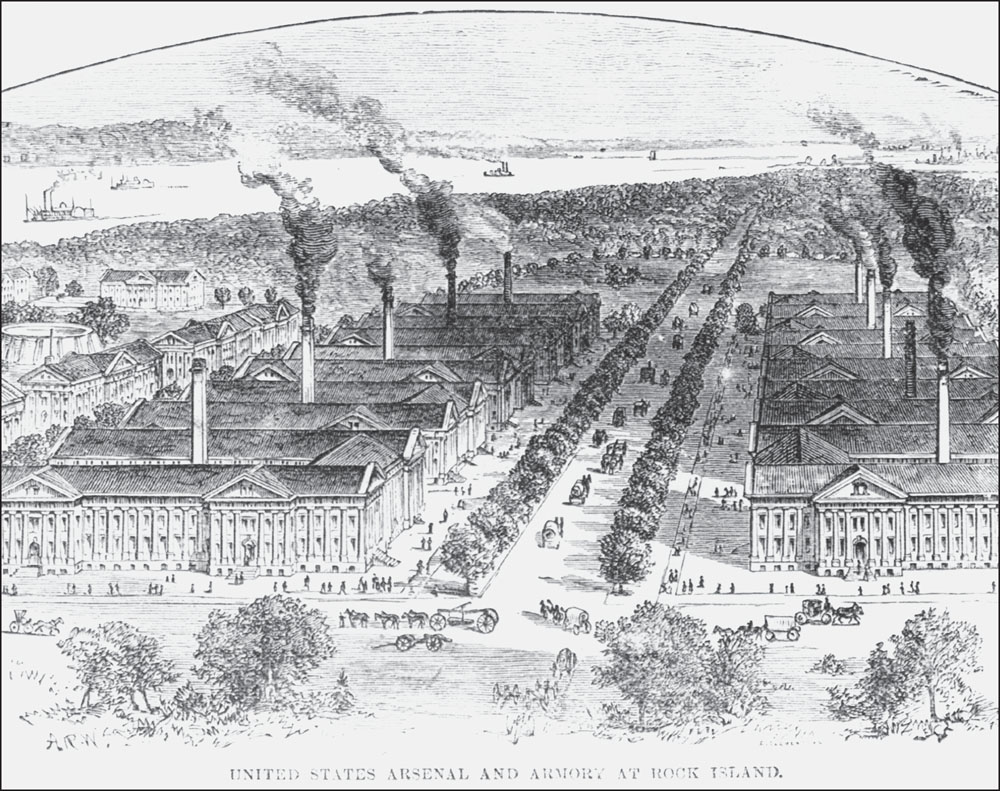

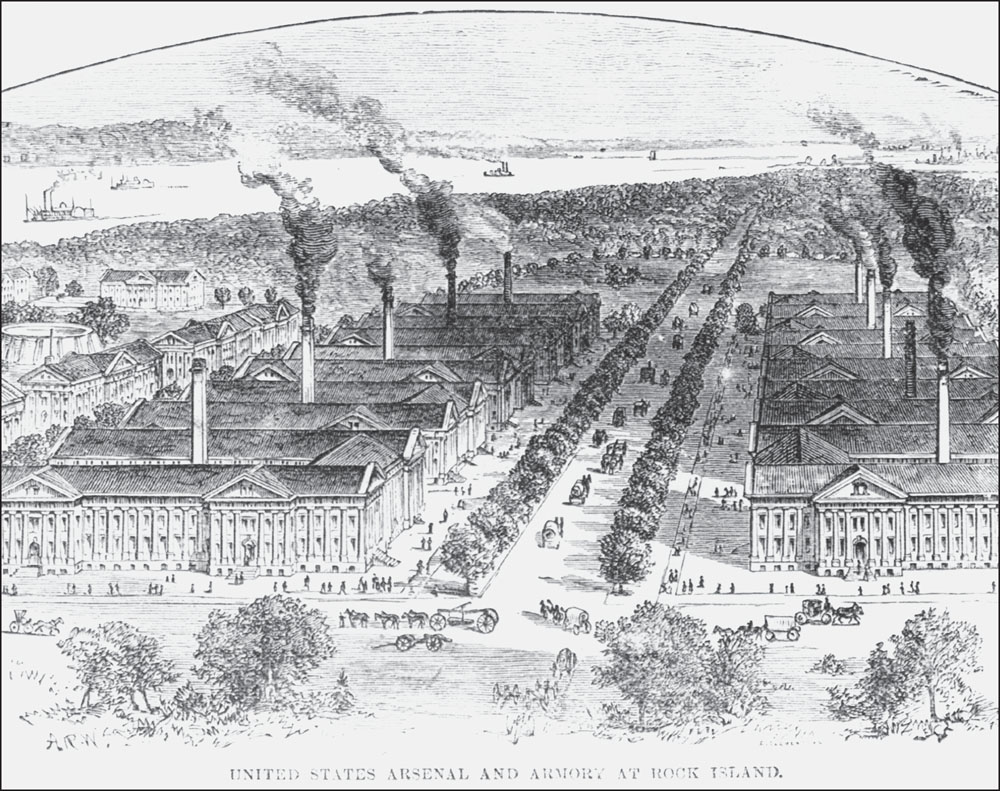

Often, an artists imagination exceeds the reality on the ground. This sketch from the late 1870s illustrates that point. The 10 manufacturing buildings that are the core of Arsenal Island are shown, but only two tall chimneys and two of the support buildings seen behind the main manufacturing shops were ever built. However, the sketch gives the impression of vitality and action, which was probably the intent. (Courtesy of the Rock Island Arsenal Museum.)

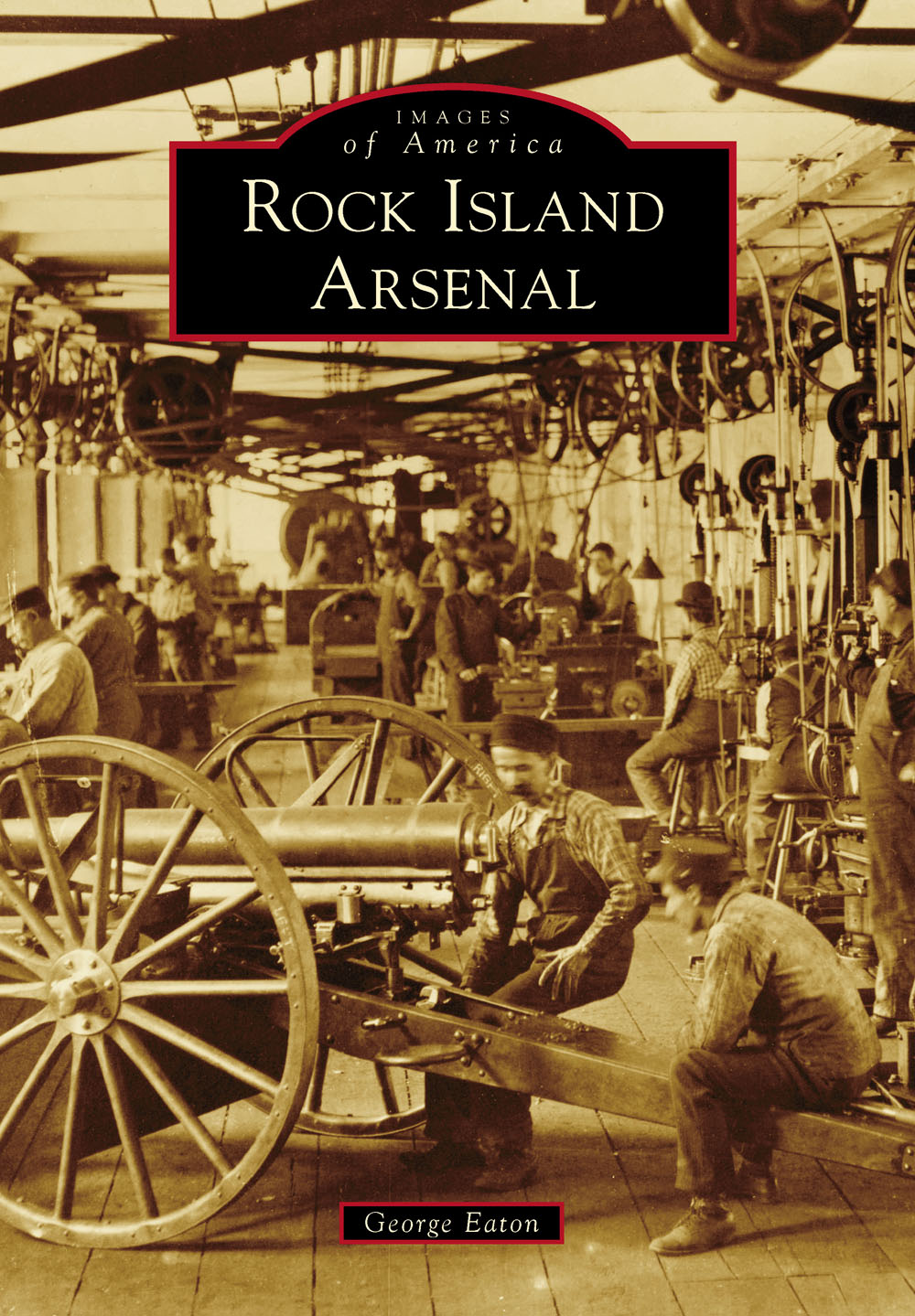

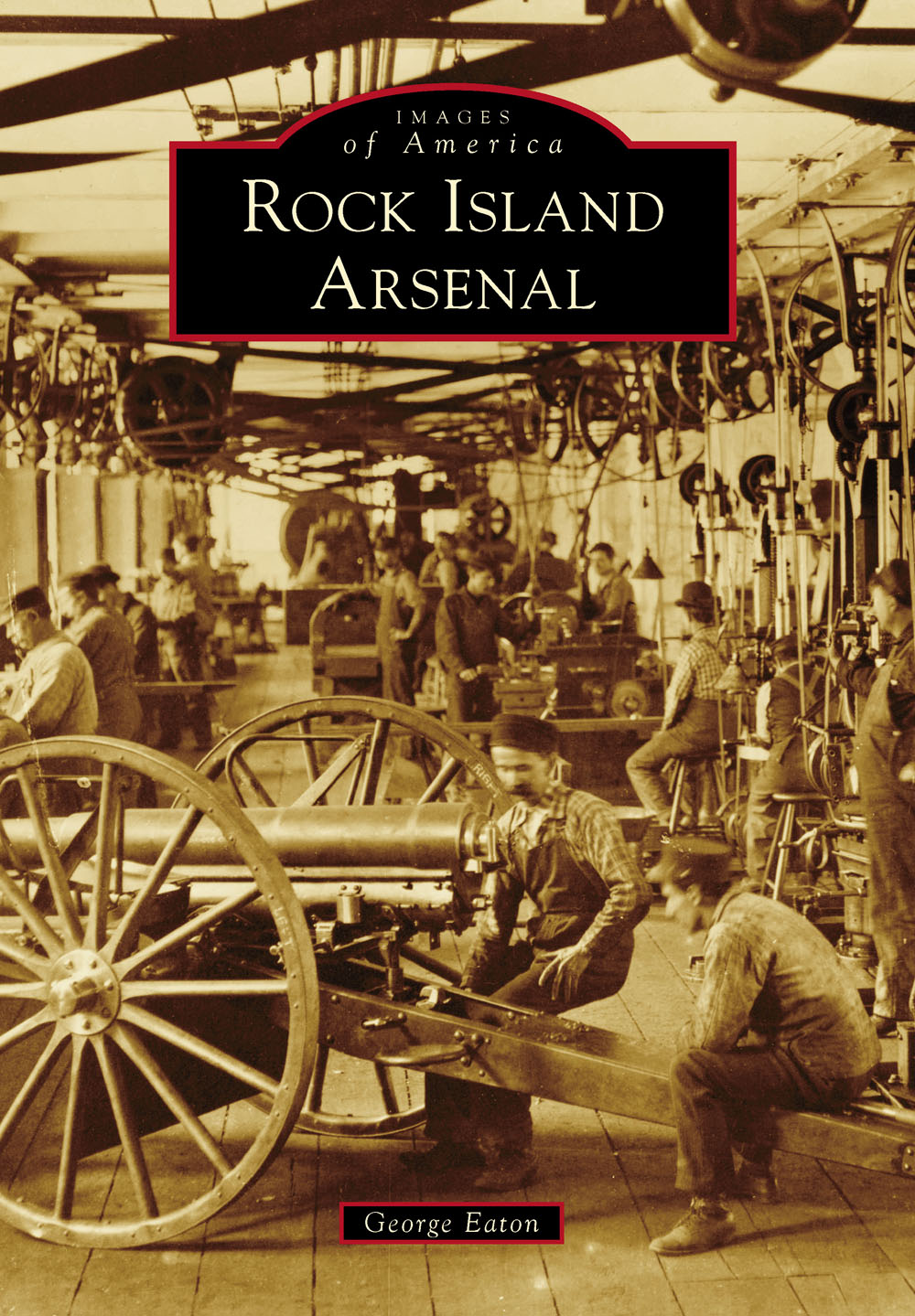

ON THE COVER: Rock Island Arsenal manufactured artillery before the end of the 19th century. The arsenal performed so well during the Spanish-American War (18981900) that it was made the national artillery assembly center and designed carriages and caissons. In this 1904 scene, three-inch guns are assembled in Shop G, Building No. 108. The straps ran the machinery. (Courtesy of the Rock Island Arsenal Museum.)

IMAGES

of America

ROCK ISLAND

ARSENAL

George Eaton

Copyright 2014 by George Eaton

ISBN 978-1-4671-1270-3

Ebook ISBN 9781439648735

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014936331

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

This book is dedicated to the historians and museum curators who tell the story of the Rock Island Arsenal and the people who make it run.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Rock Island Arsenal rose from the hard stone of Rock Island beginning in 1862; however, in reality, Arsenal Island has been the heart of the Quad Cities Area for almost 200 years. As the oldest establishment in the area, the Armys presence on the island affected the towns of Davenport and Bettendorf in Iowa, and Moline and Rock Island in Illinois, as well as numerous other smaller towns in the area. Rock Island Arsenal impacted the area as an employer, business opportunity, and visual cue. The massive stone structures on the island in the middle of the Mississippi River stand out and draw attention. One still notices the energy and activity of the Armys last great arsenal able to melt, pour, and finish metal; receive, store, and issue materiel; run a 130-year-old bridge; and, more quietly, manage a massive proportion of the Armys logistics infrastructure.

Of great luck in developing this book is the fact that the Army was always interested in documenting its presence on the island. For this volume, I needed to look no further than the collections of the Rock Island Arsenal Museum, the US Army Corps of Engineers Rock Island District Library, and the US Army Sustainment Command History Office Archives for photographs and maps. Publication of this book shines much-deserved light on their efforts to ensure the story of the island is not forgotten.

I would like to especially acknowledge and thank Kris Leinicke, director of the Rock Island Arsenal Museum, along with Jodie Wesemann and Bill Johnson, for all their assistance; Robert Romic of the Corps of Engineers Library; and Kiri Hamilton, a dedicated volunteer at the Army Sustainment Command History Office. In addition, I want to acknowledge Dale Heiser of the museum for assisting in the scanning of photographs. Clyde Cocke and Chris Crawford started this project and passed it to me. Thanks to them for the initial work and the collection of many photographs. Thanks also to Julia Simpson at Arcadia, who kept me on schedule and provided the best advice. Finally, I want to thank the Rock Island Arsenal Historical Society for supporting the Rock Island Arsenal Museum. All of the authors proceeds from this book will be donated to the historical society.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are courtesy of the Rock Island Arsenal Museum.

INTRODUCTION

In 1805, Lt. Zebulon Pike set foot on what may have been called Rock Island but is now most often called Arsenal Island. The future home of Rock Island Arsenal was uninhabited, but it was known as a summer retreat for the local Sauk and Meskwaki tribes. In his autobiography, Black Hawk described the island:

It was our garden, like the white people have near their big villages, which supplied us with strawberries, blackberries, gooseberries, plums, apples and nuts of different kinds. Being situated at the foot of the rapids, its waters supplied us with the finest fish. In my early life I spent many happy days on this island. A good spirit had charge of it, which lived in a cave in the rocks immediately under the place where the fort now stands. This guardian spirit has often been seen by our people. It was white, with large wings like a swans, but ten times larger.

To the Army, the island was more important as a potential spot to provide security along the Mississippi River. While the Unites States had, through the Louisiana Purchase, just acquired the west bank of the river and hundreds of thousands of square miles, even the east bank of the Mississippi north of St. Louis was beyond the frontier and unknown territory. Pikes explorations were intended to find the headwaters of the Mississippi, which he missed, and develop information and maps about the river and its inhabitants, at which he was more successful. Rock Island was, and remains, the largest island on the Mississippi at over 900 acres. Located at the end of the dangerous Rock Island Rapids, the island presented an opportunity to control the upper Mississippi River by regulating traffic at the rapids. This concept of traffic control increased over time, as larger boats and then steamboats plied the waters.

In addition to the rapids, the island allowed the Army to keep an eye on the local Native American tribes who were disgruntled with the United States over the terms of the Sauk and Fox Treaty of 1804, which had transferred over 52 million acres of land to the Americans. Unhappy with the treaty when Pike arrived, the frustration led some of the tribe to ally with the British in the War of 1812. These warriors, eventually known as the British Band of the Sauk and Fox, under the leadership of Black Hawk, fought and defeated the Americans in the area at Campbells Island and Credit Island in the summer of 1814. These defeats led to the establishment of Fort Armstrong on Rock Island in May 1816. The fort was the first permanent settlement in the area, providing security for fur traders, river transportation, and, after the mid-1820s, settlers. Fort Armstrong was the administrative and logistics hub for the field forces during the Black Hawk War of 1832. After that war, with the frontier moving farther west, the fort was abandoned. At times under the control of a caretaker and at other times used as a supply depot, the old fort faded away.

One of the caretakers was George Davenport, considered the first permanent settler in the area. Davenport had been in the Army during the War of 1812 and then became a sutlera contractor who provided food and other supplies to Army units. Eventually, he quit that role and became a fur trader and land developer, building a large trading post and a modern home on the island. In 1845, just weeks before he was murdered, Davenport hosted a meeting in his house with railroad interests and discussed the possibility of erecting a rail bridge over the Mississippi at Rock Island. Based on the engineering capacity of the day, Rock Island was the only place a bridge could be placed and still be far enough south to be financially effective. Bridges could cross from the Illinois mainland to the island and then jump the main river channel to Davenport. The shallowness of the rapids and the shorter spans made this a perfect spot. While Illinois and Iowa soon granted licenses to the ChicagoRock Island line and the Mississippi and Missouri lines, the federal government refused to grant a license to cross the island. Jefferson Davis was the secretary of war and was working for a rail crossing much farther south that would potentially allow the spread of slaveholding states across the southern tier. Eventually, the rail companies took advantage of the Act of 1852, which allowed rails to cross public lands, and proceeded to build across the island. Davis tried again to block construction but was overruled by the Supreme Court. In March 1856, the first bridge over the Mississippi River opened and the area became the transportation hub of the United States. Only two weeks after the bridge opened, the steamer

Next page