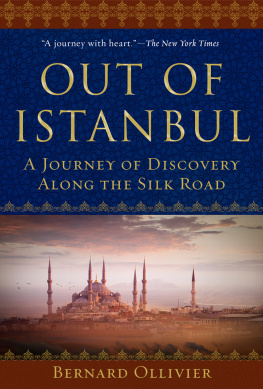

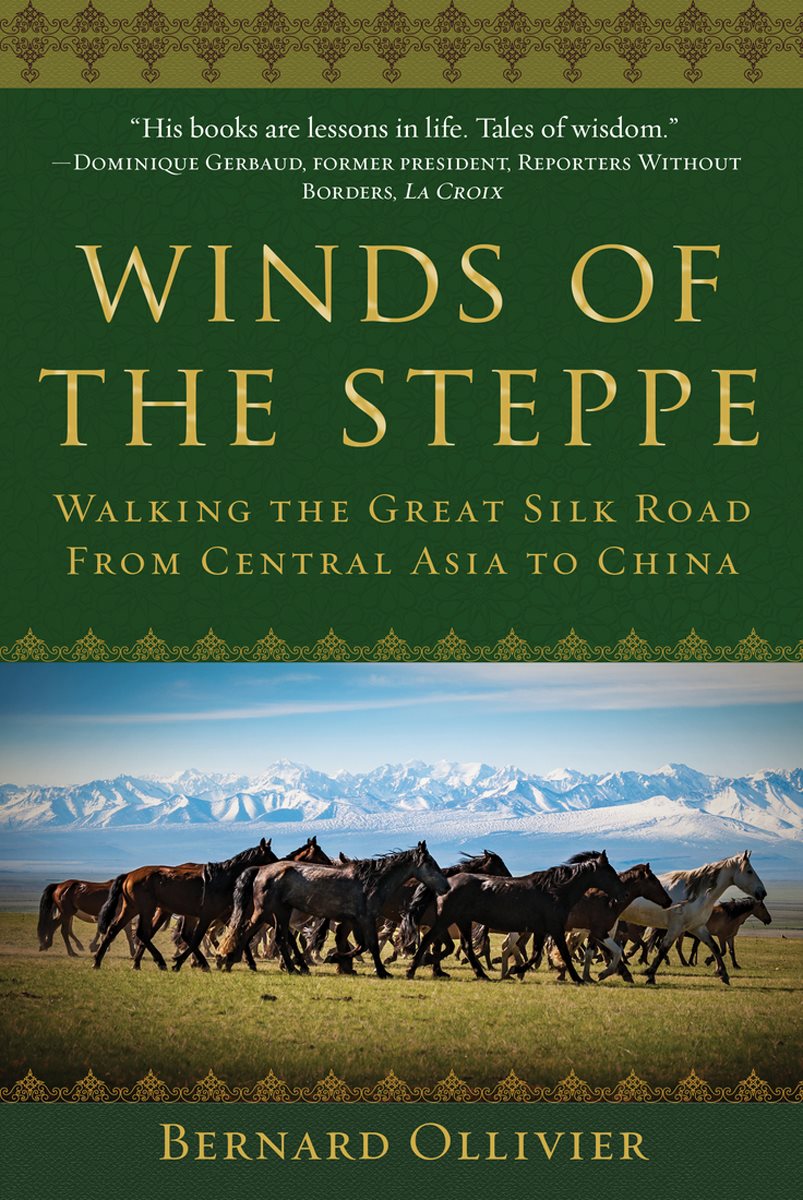

Copyright 2003 by Bernard Ollivier

Originally published in France as Longue marche: pied de la Mditerrane jusquen Chine par la route de la Soie. III.Le vent des steppes by ditions Phbus, Paris.

English translation 2020 by Dan Golembeski

The translator would like to express his thanks to Dr. Jennifer Wolter of Bowling Green State University for her insights and suggestions, and to Jon Arlan for his careful revisions and constructive comments. This translation was made possible by a 2017 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

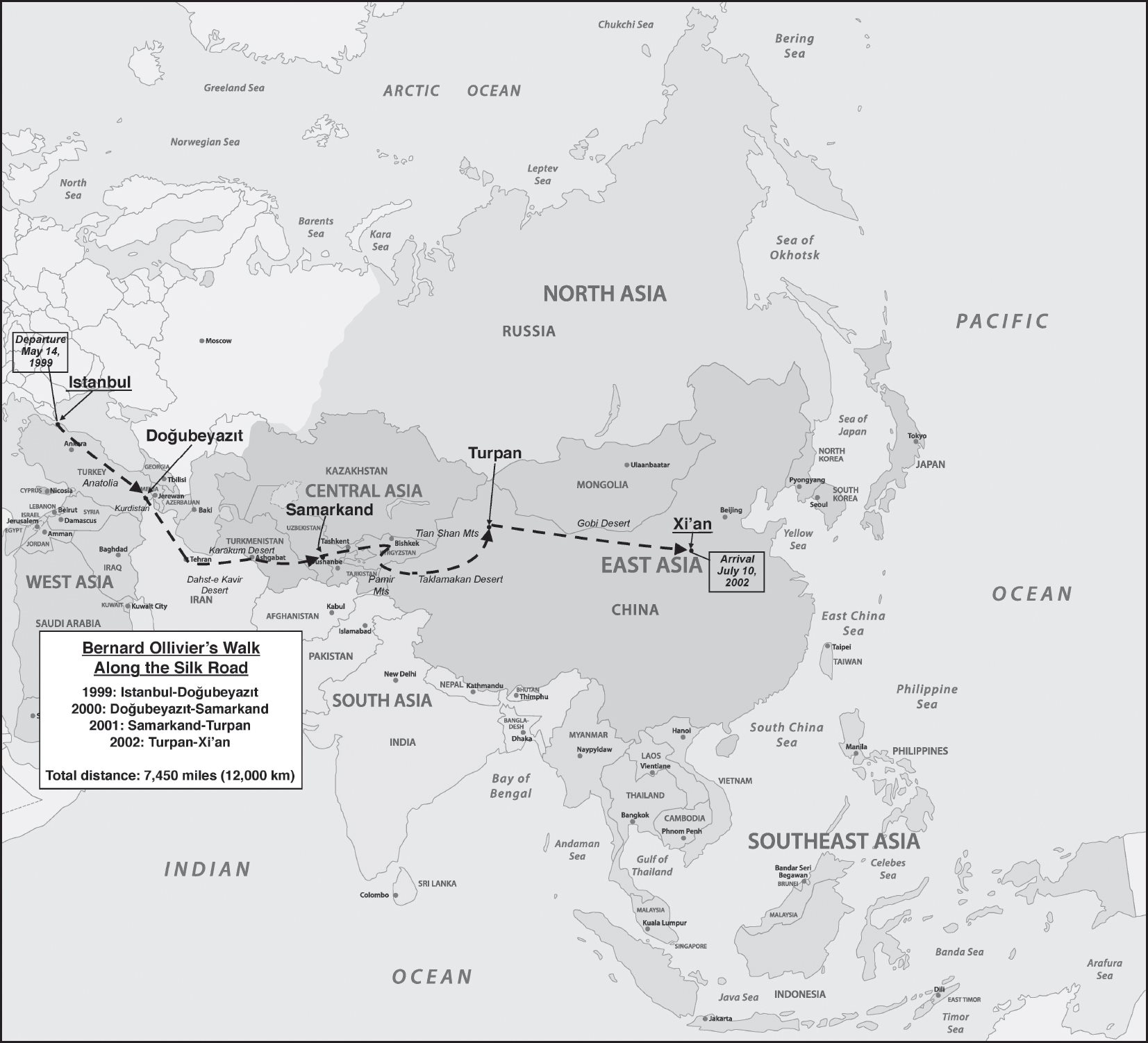

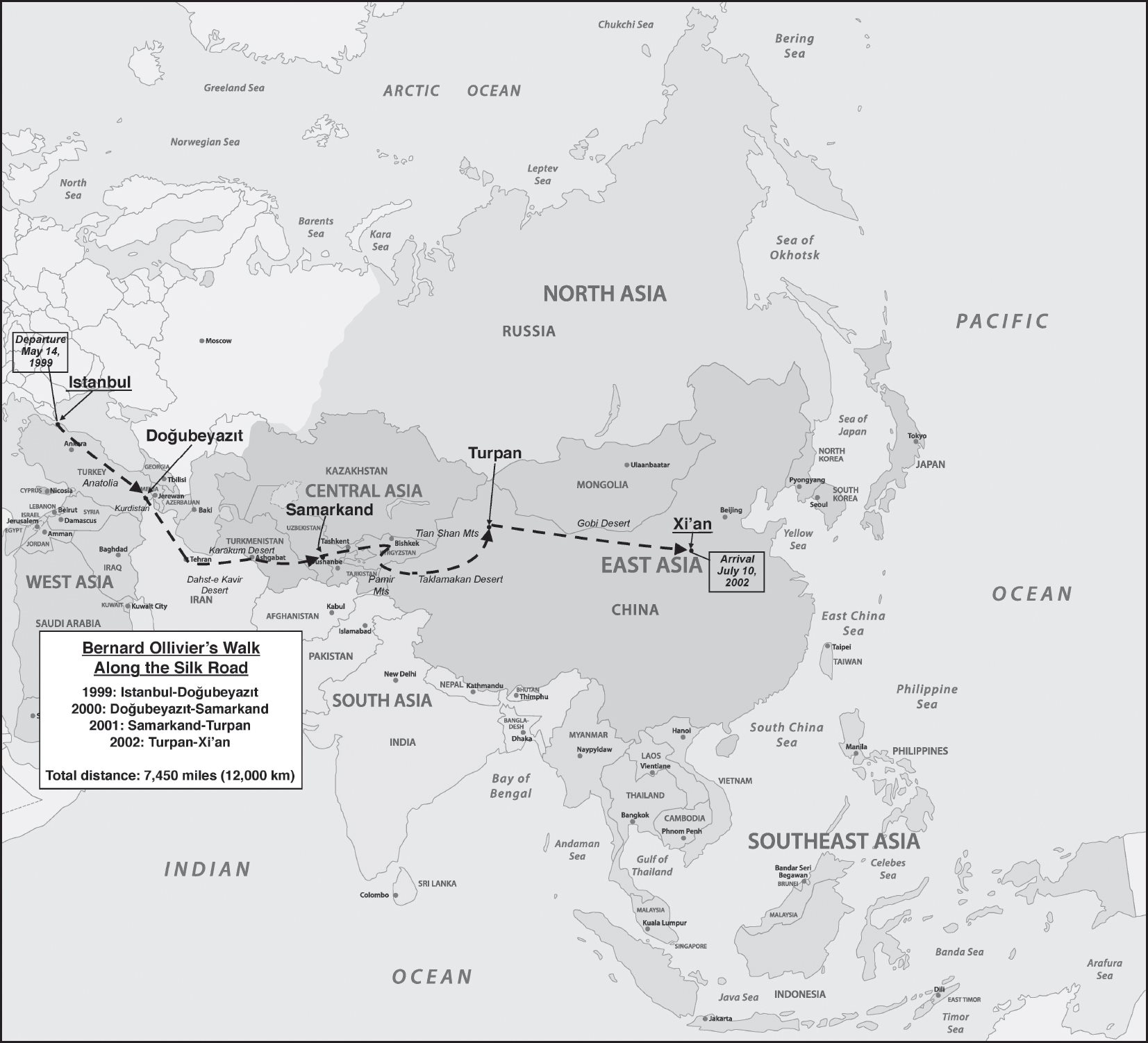

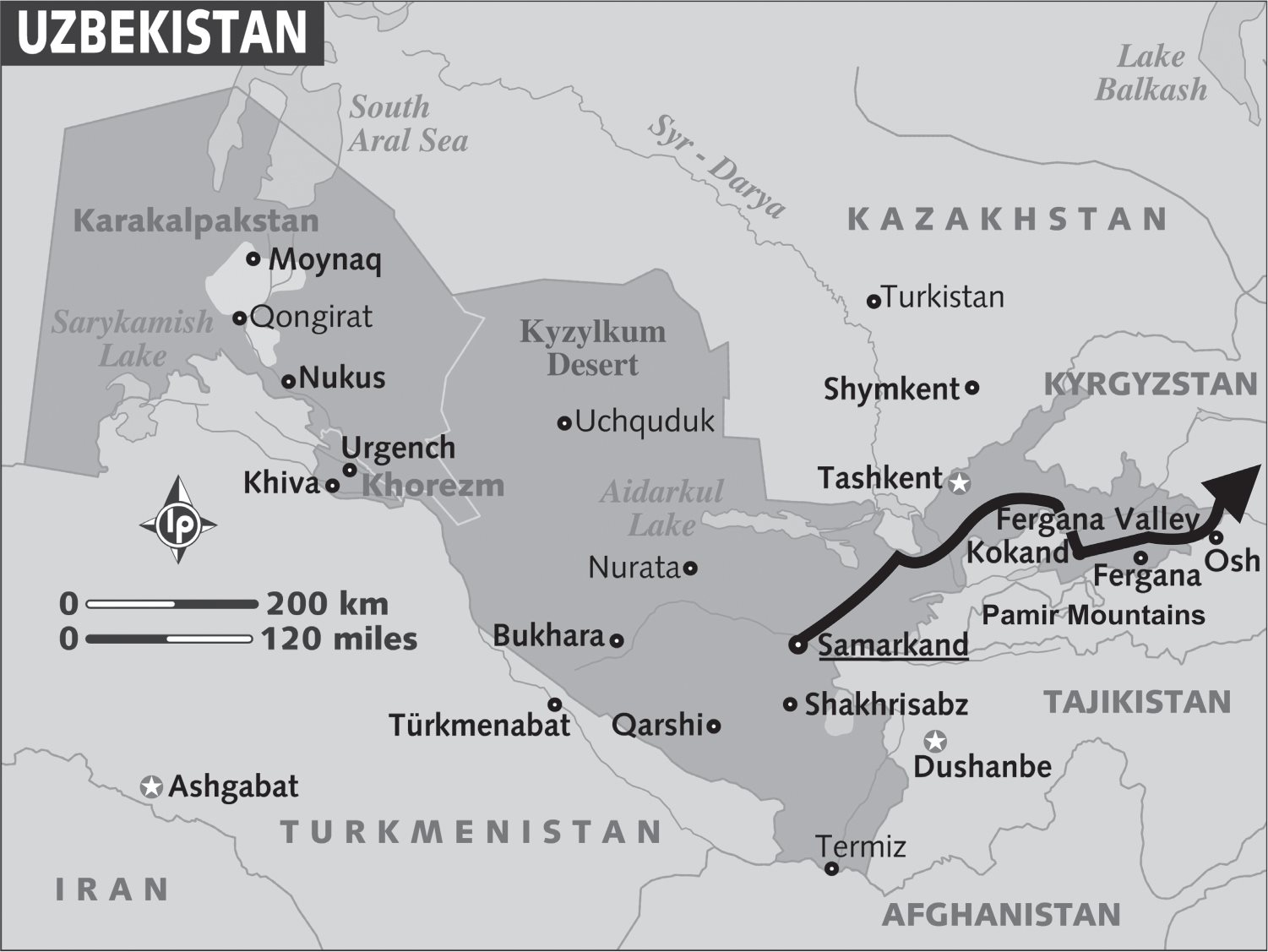

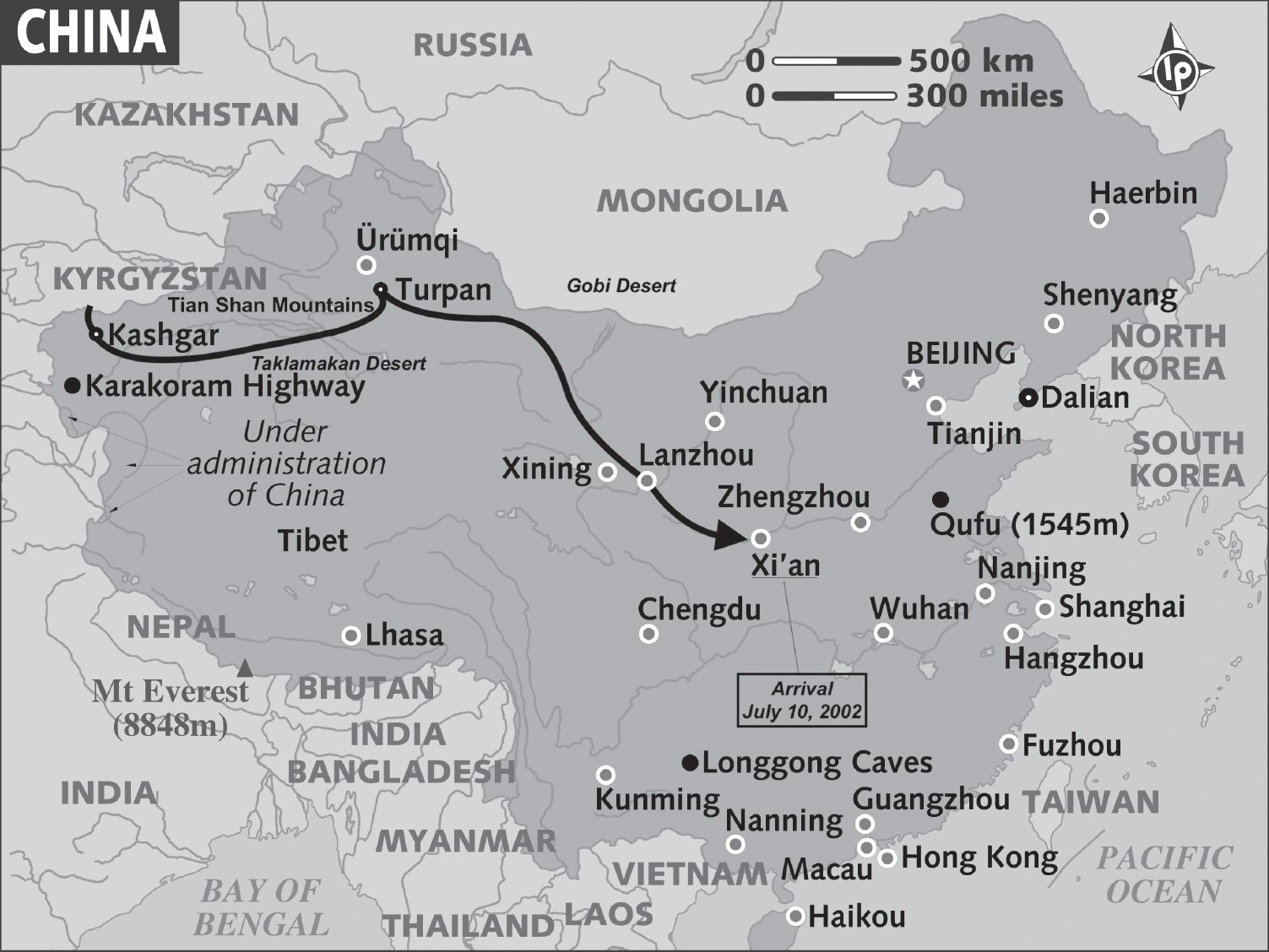

Maps: iStockphoto, Getty Images

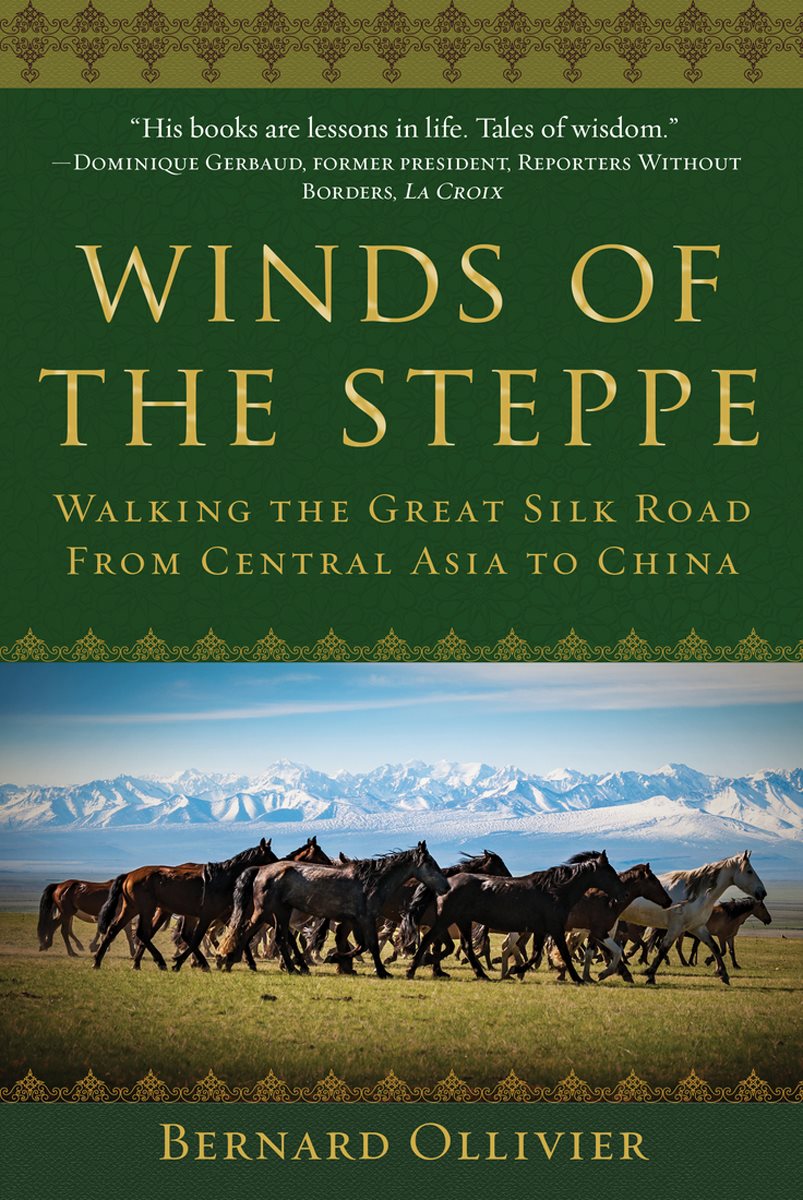

Cover design by Brian Peterson

Cover photo credit: Getty Images

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-4690-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-4692-3

Printed in the United States of America

To Sofy

OTHER BOOKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR AVAILABLE IN ENGLISH

Out of Istanbul: A Journey of Discovery along the Silk Road. Skyhorse Publishing, 2019.

Walking to Samarkand: The Great Silk Road from Persia to Central Asia. Skyhorse Publishing, 2020.

CONTENTS

PART ITHE HEIGHTS OF THE PAMIRS

THIRD VOYAGE

(SummerAutumn 2001)

I

LEAVING

Leaving, they say, is the hardest thing to do. But leaving yet again is harder still.

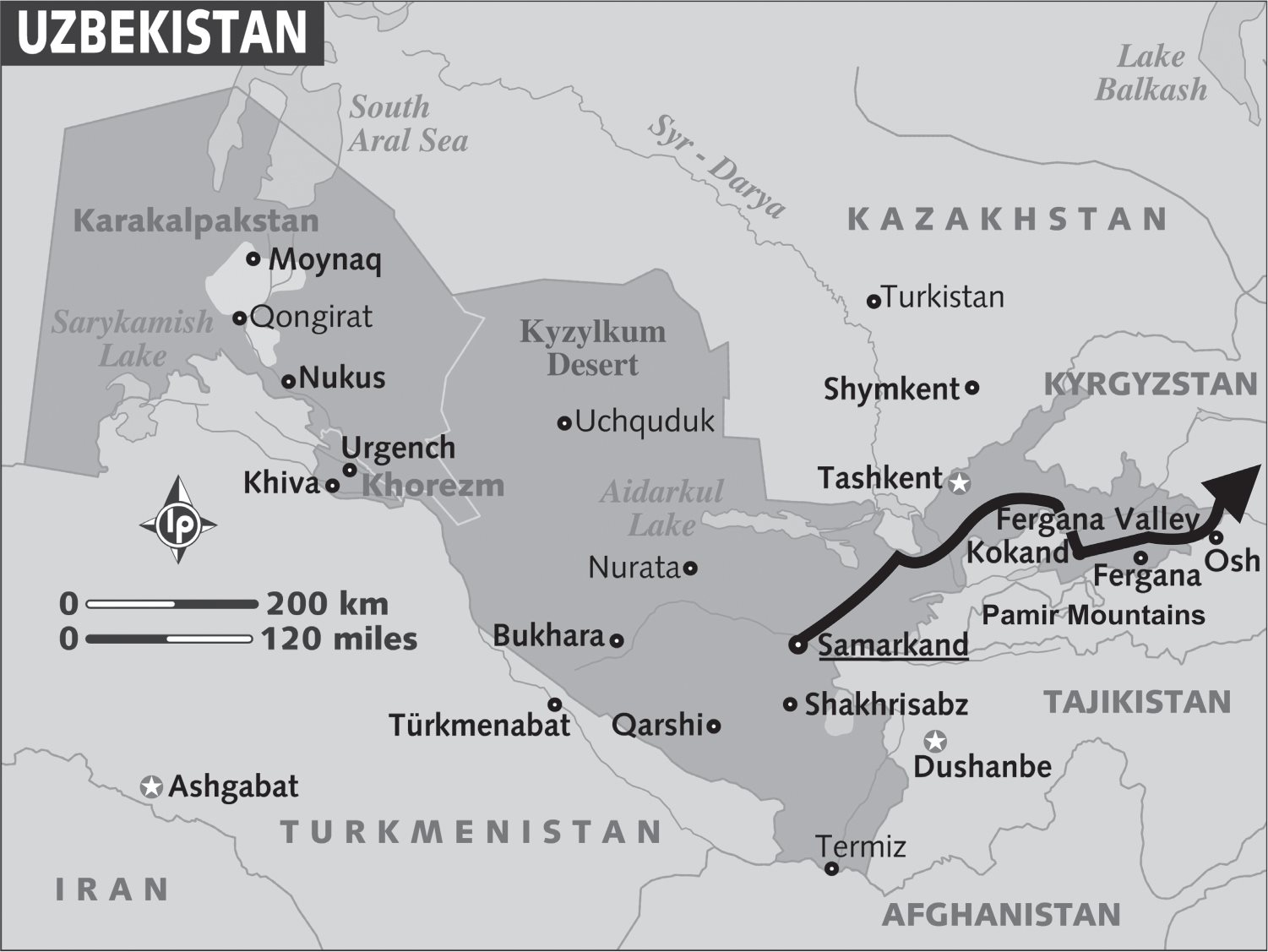

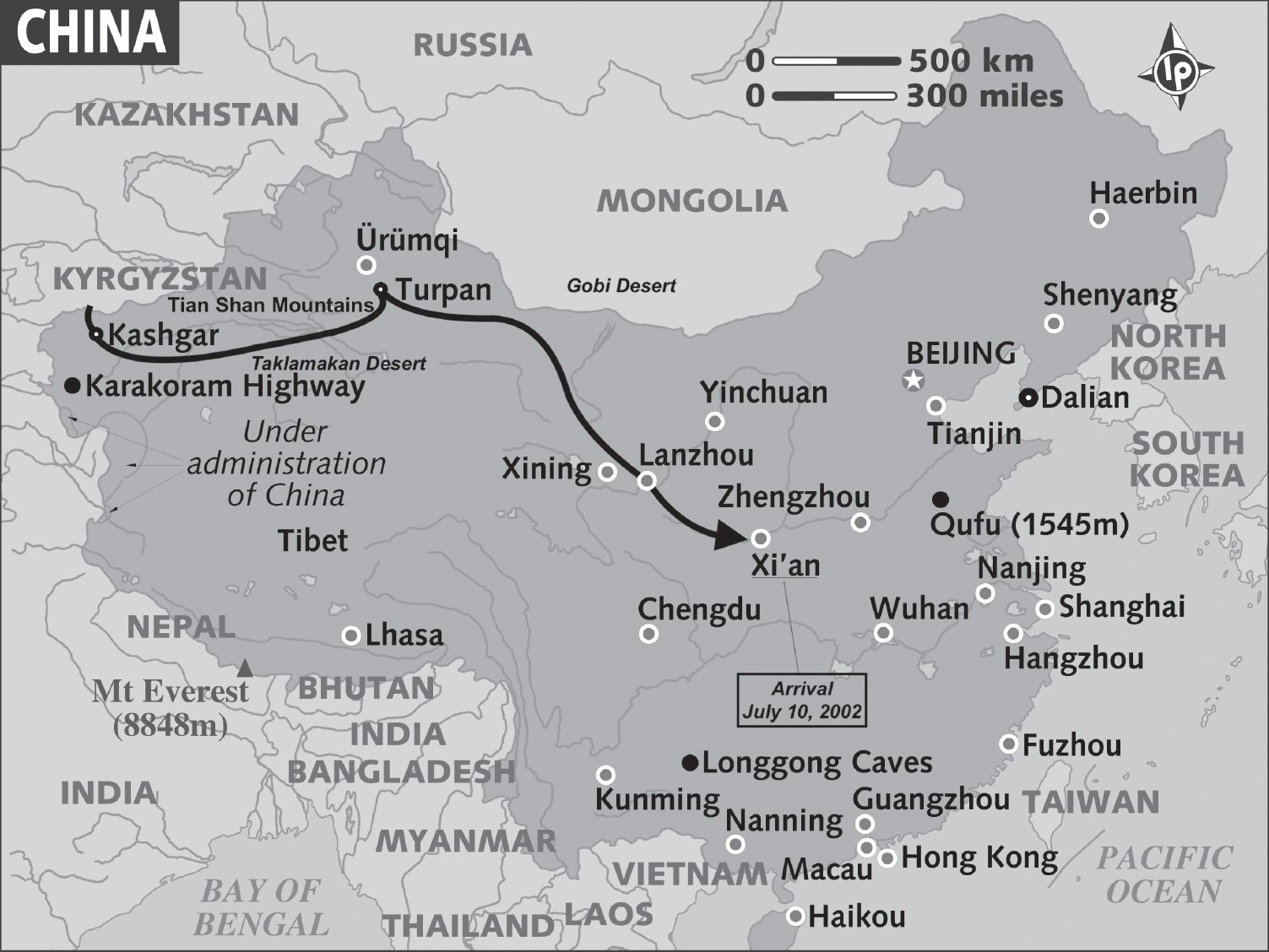

After starting out from Samarkand, Uzbekistan, two days ago, here I am back on the Great Silk Road, which has obsessed, delighted, and terrified me for two years now. My body protests: aching muscles, legs that refuse to go the distance, a feeling of unquenchable thirst brought on by the sudden heat, and nights filled with erotic dreams as my sex drive tries to hold out against the imposed fast. Despite what they say, the first step is not always the toughest. In the beginning, every single mile is torture. But most agonizing of all is tearing myself away from those I love. Yesdollar-hungry cops and robbers, the frozen heights of the Pamir Mountains Ill have to cross, and the Taklamakan Desert (meaning in Uyghur, the place from which one never returns)all that will be my lot over the course of the 120 days of my 2001 walk. But no nightmare will be worse than the terrible isolation Ill have to endure all the way to Turfan, that burning oasis, which the Chinese have nicknamed the Land of Fire. I never get used to being alone. Still, today, more than ever before, I find myself craving the adventures, encounters, and joys that this intoxicating road has lavished upon me so far.

Its been two days since I took leave ofthe Chukurovs, my friends in Samarkand. Sabira, attentive soul that she is, did nothing to make my departure any easier, quite the contrary. Preoccupied with all the hardships I would soon face, she pampered me in her cozy home on the outskirts of town, gorging me with food: a large bowl full of fruit from their garden, copious servings of green tea, and revitalizing plovUzbekistans national dish, consisting of rice, vegetables, and meat. Though I had eaten my fill, she insisted on extra helpings. Its good for the heart! she repeated with each additional spoonful, her kind, grandmotherly eyes smiling out from behind thick-lensed glasses obscuring much of her face. To help get me ready for the hell Im heading into, she had transformed her patio into a little piece of paradise. As darkness fell, her granddaughters, Yulduz and Malika, and her son, Faroukh, kept me company around a basket of melt-in-your-mouth cherries. I had brought with me a copy of my book telling of my walk in the year 2000, and of the warm welcome their family had given me. Mounikha Vakhidova, who assisted me during my stay in Samarkand last year, translated my account of it for them. Sabira was moved to tears: While my husband was alive (he had been a literary critic celebrated throughout the Soviet Union), fifty authors from around the world stopped by our house each year. But none of them ever put my name in a book!

Winter had been ruthless this year with temperatures dropping to -13F. Pipes burst in the walls. A spring drought caused wells to dry up. People living outside the city limits have no more water and the apricots have ripened a month earlier than usual. The day before yesterday, things got even worse. The chilla, a period of scorching heat lasting forty days, suddenly hit. In two or three days, the sarafon will follow: lasting a full month, its the hottest wave of summer heat, and, with its flaming arrows, it could very well prevent me from walking.

Ive chosen the worst possible time to get underway. But did I really have a choice? I had to decide whether to bake at the outset of my journey and head into the Fergana Valley at the hottest time of the year, or to leave much earlier and arrive in the Taklamakan Desert at the worst possible moment. Turfan, my final destination, is the hottest place in all Chinathough the entire country experiences blistering summer heat. Ive made up my mind to sweat it out at the beginning so as to have cooler weather at the end. Its that childhood dilemma we have to deal with all of our lives: which should we eat first, the bread or the chocolate? To top it all off, I have to time my journey so that I reach the Pamir Mountains no later than August or early September, to avoid the possibility of snowstorms as winter draws near and reach my destination before mountain passes close down in this region known as the roof of the world.

I added my last few pounds on the eve of my departure in Mounikha Vakhidovas small apartment. She speaks excellent French, delightfully rolling her Rs. In this convivial Tower of Babel, each of her friendssome Tajik, some Uzbekspeaks in his or her native tongue since everyone understands both. The children, meanwhile, play and call to one another in Russian, and Mounikha and I speak French. When Central Asians sit down to a meal, the order in which the dishes are served matters little. Guests happily move from meats to vegetables, from sweet to savory without the slightest transition. Its a meal in which everyone nibbles at will: meat dumplings, grilled cauliflower, carrots, strained

Next page