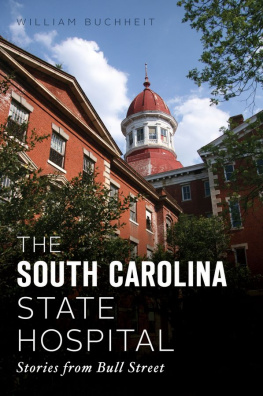

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by William Buchheit

All rights reserved

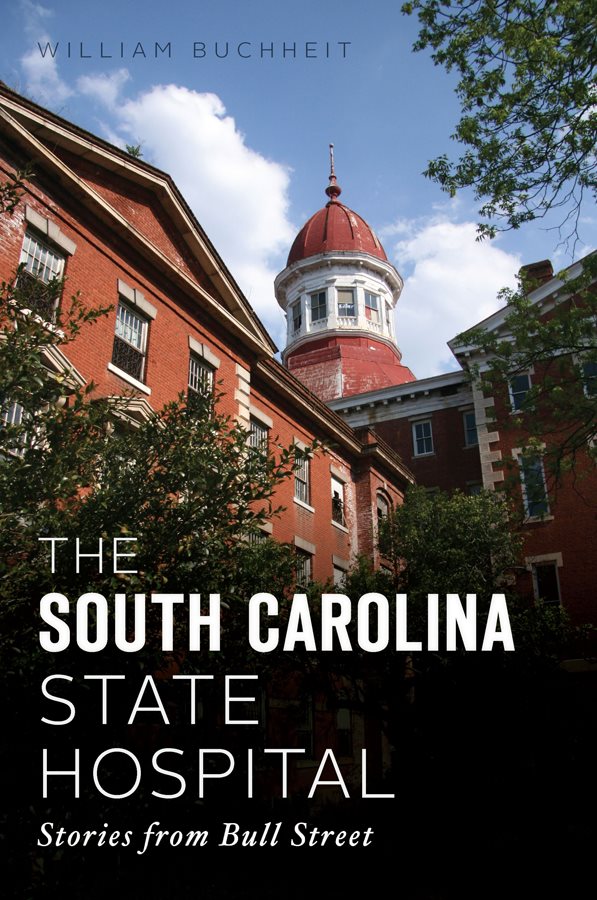

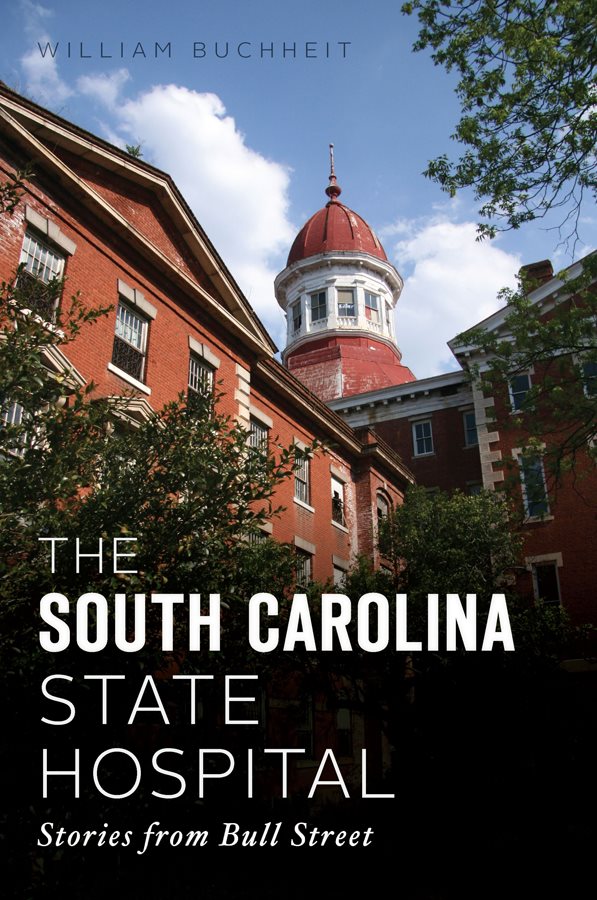

Cover photo by William Buchheit.

First published 2020

E-Book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.879.5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019951251

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.472.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For my late cousin Heather, who spent so much of her life caring for others.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First, Id like to thank the twenty-four men and women whose stories are featured in this book. They spent hours answering my questions and telling me about their lives, and most of them were able to scrounge up old photos to personalize their stories.

I also owe a great amount of appreciation to those who provided information about the South Carolina State Hospital and put me in contact with people to interview: Jan Bob Barkow, Ginny Caldwell, Jonathan Cochran, John R. Edwards, Sarah Lewis, Lorry May, Kay McCrary, Jane Westbury and South Carolinas mental health commissioner, Gregory Pearce.

Obviously, this book would not have been possible without the help of the South Carolina Department of Mental Health (SCDMH), its employees and its archives. Im particularly indebted to SCDMHs public information director, Tracy Lapointe, for her encouragement and for helping me gain clearance to photograph the campus in 2010 and 2011. Id also like to thank the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), especially South Carolinas chapter, for awarding me Reporter of the Year in 2011. Without such advocacy groups, the mentally ill wouldnt have a voice at all. My gratitude also goes out to the Aiken Standard newspaper for its stellar coverage of the SCDMH and state hospital during the second half of the twentieth century.

My genuine thanks goes out to The History Press and its editor Chad Rhoad for agreeing to publish this book.

I, no doubt, owe a degree of debt to photographer Christopher Payne. It was, after all, his photobook Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals that sparked my interest in the decline of mental institutions and the displacement of their patients.

As family members go, I owe thanks to my brother Phil for giving me photography pointers in my early days of exploring and shooting the Bull Street campus.

I also owe credit to my sister Bonnie and mother, Mellnee, for their continued love and support during the long process of writing this book. Im grateful as well to my aunt Brenda for giving me firsthand accounts of her visits to the hospital to see a patient in the late 1960s.

Lastly, I want to thank all the former South Carolina State Hospital patients who contacted me with their own stories of life on Bull Street. Your help was essential to my study of the iconic institution, and it helped me better understand all the institutions strengths and shortcomings.

INTRODUCTION

In early 2010, I was ambling through a Barnes & Noble when a large photobook caught my eye. Under the covers image of a dangling straitjacket screamed the title in red capital letters: ASYLUM: INSIDE THE CLOSED WORLD OF STATE MENTAL HOSPITALS.

The second I opened the book, I was captivated. Its creator, New York photographer Christopher Payne, had visited dozens of abandoned state hospitals across America, shooting both the interiors and exteriors of the castle-like structures.

Perhaps the most illuminating facet of Paynes work is its assertion that these institutions did a lot more than treat and house the mentally ill. In essence, they functioned as self-sustaining communities with their own greenhouses, slaughterhouses, bowling alleys, dairies, stables, laundries, cemeteries and full-service medical facilities. However, the thing I found most interesting about Asylum was the way it provided a visual history of psychiatric treatment in our country. Most of the hospitals Payne photographed have been reasonably well preserved and remain intact; anyone who tours the hospitals is transported to a bygone era when the colossal structures pulsed and howled with the afflicted.

Asylum did more than spark my curiosity and imagination, it created a yearning in me to see and photograph one of these old mental hospitals firsthand. The asylum closest to my house in Upstate South Carolina is the South Carolina State Hospital in downtown Columbia. It was a sprawling 180-acre property that was tucked away from the general public for nearly two centuries. Known statewide as Bull Street because its entrance lies at the corner of Bull and Elmwood, the South Carolina State Hospital is the nations second-oldest public mental facility, admitting its first patient in 1828.

Even though Id lived within a mile of the institution as a graduate student from 1998 to 2001, Id never once been inside its gates. All that changed on Superbowl Sunday 2010, when I drove through the campus on my way back home from a bachelor party in Charleston. It was a cold, wet afternoon, and since I had no game plan at the time, I drove toward the single-level structures at the rear of the property. Eventually, I parked my car behind the Saunders Building, where it would be less visible, and grabbed my camera. A few minutes later, I was scouring the back porch of Saunders when I discovered a door that had been propped open. With my heart hammering against my sternum, I pushed the door forward and squeezed through the opening to get inside.

The Saints and Colts were just hours away from kicking off the Superbowl, but its hard to imagine that any of the players were as excited and nervous as I was inside those unfamiliar surroundings. Perspiration stung my scalp as I inhaled the musty air and gazed at the thick strips of paint peeling off the walls. It was clear the building hadnt functioned as a hospital for at least a decade, because there was little in the way of artifacts to be found. Yet, the darkness, silence and decay trapped inside the building had an inescapable allure. I thought about the prospects of ghosts, security guards and homeless people finding me inside, but most of all, I wondered about what had taken place in the hospital when it flowed with life.

Over the next eighteen months, I returned nearly two dozen times to explore and photograph the decaying hospitals campus. Along the way, my interest in Bull Street went from abstract curiosity to undeniable obsession. As many hours as I spent creeping through the menacing darkness of the hospital, I spent just as many off campus researching the institutions history. I found it stunning how little had been written about the hospital and continued to think about all the lives that had been saved, changed and lost there.

During those years of research, I was still working full time for a chain of newspapers in Spartanburg, and I thought it might be interesting to write a series on Bull Street. Who better to tell the story of the hospital, I figured, than the men and women whod worked there? So, I spoke with employees of the South Carolina Department of Mental Health (SCDMH) and asked if they could point me toward any interesting interviewees. Most people gave me the same name: Woody Harris. Around Columbia, Harris had earned a reputation as the state hospitals unofficial historian. As you will read in the first chapter of this book, the interview did not disappoint. Over a couple hours at his house, Harris relayed stories about the good, bad and ugly things that hed witnessed during his long career at Bull Street. To me, it was the worlds most interesting place, he explained.

Next page