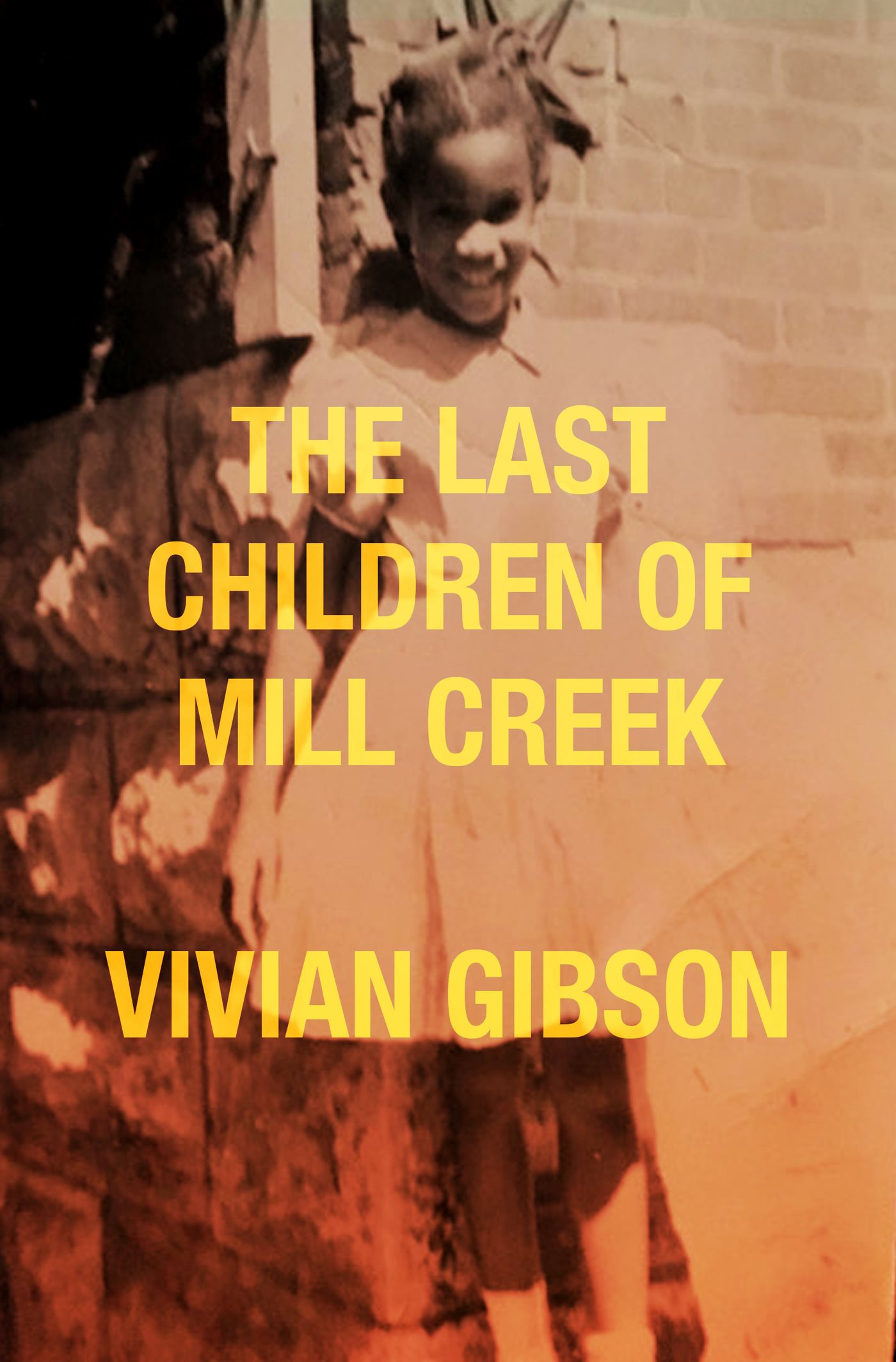

THE LAST

CHILDREN

OF MILL CREEK

THE LAST

CHILDREN

OF MILL CREEK

Vivian Gibson

Belt Publishing

Copyright 2020 by Vivian Gibson

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Excerpt from Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks reprinted with consent of Brooks Permissions.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition 2020

ISBN: 978-1-948742-64-1

Belt Publishing

3143 W. 33rd Street #6

Cleveland, Ohio 44109

www.beltpublishing.com

Book design by Meredith Pangrace

Cover by David Wilson

For my parents,

Frances Elizabeth Hamilton Ross

and

Randle Henry Ross

Contents

What she liked most was candy buttons, and books, and painted music and the west sky, so altering, viewed from the steps of the back porch; and dandelions.

But dandelions were what she chiefly saw. Yellow jewels for everyday, studding the patched green dress of her back yard. She liked their demure prettiness second to their everydayness; for in that latter quality she thought she saw a picture of herself, and it was comforting to find that what was common could be a flower.

Gwendolyn Brooks, Maud Martha (1953)

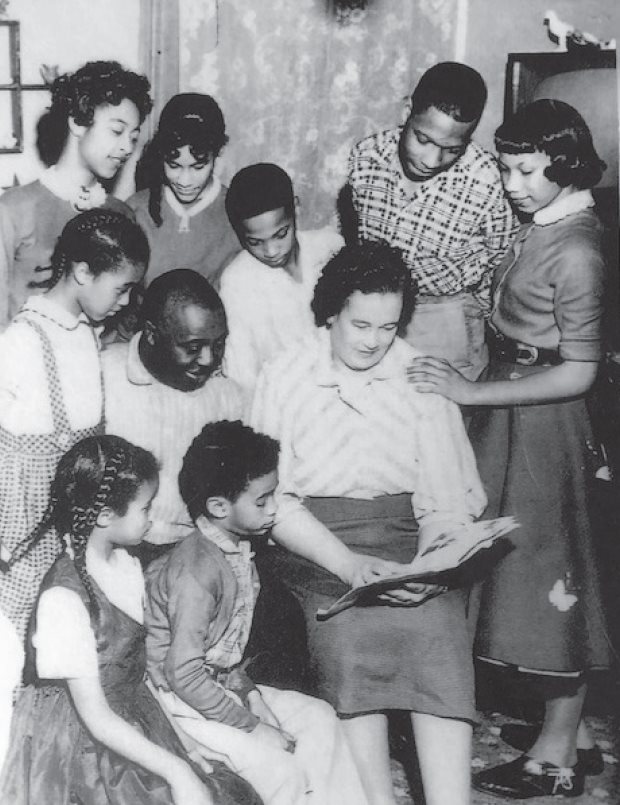

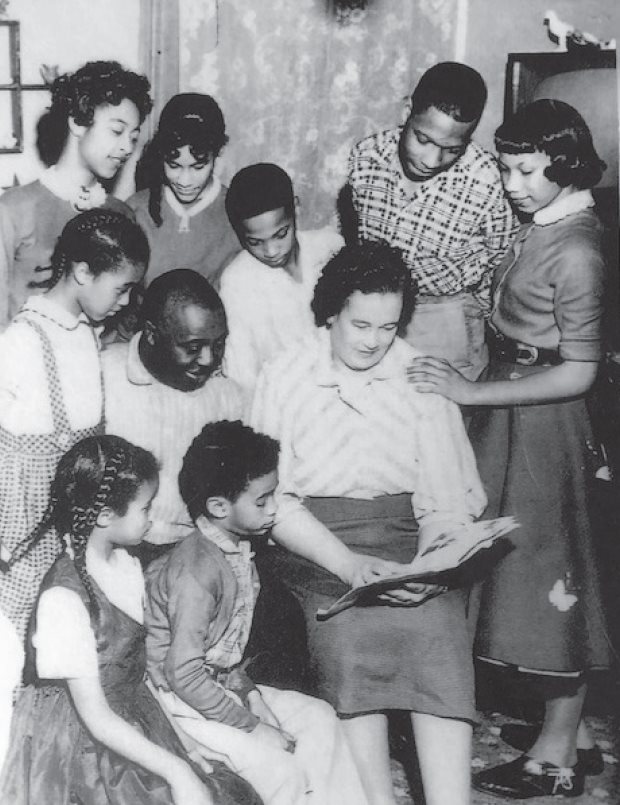

Ross family, 1956, as printed in the St. Louis Argus with the caption 100% N.A.A.C.P. members. While Mrs. Ross spends numerous hours doing volunteer work in the N.A.A.C.P. office, the children are members of the junior youth and senior youth council.

Back row from left: LaVerne, Carol Jean, Shepperd, Randle, Beverly. Middle: Tootie, Randle H. Ross, Frances Ross. Front: Vivian and Ferman

INTRODUCTION

I did what Mama told me to do: Move away so that I can have someplace to visit.

I moved to New York City in the summer of 1970. She visited me once in my third-floor walk-up in a brownstone on West 138th Street, between Broadway and Riverside Drive. At night, if I leaned against the right side of the window frame in my living room, I could look past Riverside Drive, over the West Side Highway, and down the Hudson River to the lights of the Jersey City waterfront. Or, I could look directly across the street through my neighbors blinds that he never closed. But Mama seemed to enjoy just being in my space, among my things. She admired my secondhand furniture, much of which I had salvaged from posh Upper East Side curbs on bulk trash day. And she complimented the quality of the refinishing and reupholstering that I had spent several Saturdays working on before her visit. I had recently bought my first piece of new furniture: a chocolate brown Castro sleeper sofa that I slept on while she slept in my bed. It was the most money I had spent on any one item. During her weeklong stay, my favorite moment was walking up the stairs one day after work, hearing the television, and smelling chicken and dumplingsjust like when I came home after school as a child.

My mother didnt get to see my favorite New York apartment (my fifth in six years). I sent her the new address in a letter describing the view from the French doors in my spacious living room. It was an iconic Morningside Heights city scene, overlooking the treetops of Morningside Parkthe park that divided what comedian George Carlin called white Harlem, at the top of the sloping green space, from black Harlem, at the bottom of serpentine stone steps.

It was on the eastern edge of Columbia University at the highest point in Manhattan. In the distance, through a crowd of gray and brown apartment buildings with turret-like water towers on their roofs and fire escapes cascading down their sides, I could see the vertical marquee of the Apollo Theater on 125th Street. When Mama received my letter in St. Louis, she called me and said with a sigh, Oh, I love the sound of your new address: 54 Morningside Drive. It sounds so prosperous.

I was twenty-seven when my mother died in 1976. It was then that I realized how few in-depth conversations wed had about anything, ever. By then, it was too late. My parents hardly ever talked about their lives before we were a family. I guess they were too busy working and raising eight children to ruminate on the past. And I was too busy thinking about myself to consider what was not shared. Besides, I thought we had plenty of time for talkinguntil we didnt.

I began writing family stories for my children before I had them. The loss of my mother, and, less than a year later, my father, created an urgency about preserving my memories for the children I would have someday. Children that my parents would never meet.

I remember a few stories from when Mama and her older sister would laugh and reminisce about their childhood in Alabama. She would answer any direct questions Id ask about her childhood, but she rarely elaboratedas Dragnets Sergeant Friday would say: Just the facts, maam. A college scrapbook found in the back of her closet yielded a bounty of pictures, notes, sorority memorabilia (she was a Delta), vacation postcards from friends, and even a postmarked envelope and note from my father that established when they met.

When I was in college, I read about the wave of African Americans who left the South by the thousands during the first Great Migration, between 1900 and 1940. My parents never mentioned it, but they were part of that exodus. They arrived in St. Louis eight years apart and under very different circumstances. Daddy came around 1929, with his mother and stepfather, from rural Arkansas so that he could attend high school. There was no high school for blacks near their town, and he was the first in his extended family to go beyond third grade. St. Louis was then a hostile city for black Americans: a former hub of the slave trade, with established customs, state laws, and zoning policies that mandated segregated schools and neighborhoods. Nonetheless, they considered their move a step up from the impoverished sharecropping life theyd left behind, just one state away in the South.

Mama came eight years later. She was a pampered, middle-class college student from a small Alabama town where her father, a successful farmer, owned the colored grocery store. She came to St. Louis to visit relatives while on summer break. After my parents met that summer, and again at the next winter break, they soon married. My mothers life changed dramatically. They settled into a Negro neighborhood in downtown St. Louis called Mill Creek Valley and had eight children in rapid succession during the decade of the 1940s.

Mill Creek was one of the oldest parts of St. Louis. On land first developed by the Osage Nation, at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, it had been home to every new European immigrant group that arrived in the city over the previous one hundred years. As as a French fur trading post at a bend in the Mississippi River, the central corridor grew westward, following the creek that powered one of the first grist mills in St. Louis. The Mill Creek, as it became known, meandered from a spring near the current-day Chouteau and Vandeventer Avenues and emptied into the Mississippi River. Early citizens built grand homes near the shores of the creek; cattle grazed and watered at its edge. A dammed section became a man-made lake called Chouteaus Pond and was the site of the citys first public park (near where Busch Stadium is today). As the city grew, smoke-belching factories and foul-smelling slaughterhouses replaced the pastoral splendor along the bluffs of Mill Creek. Pollution and a cholera epidemic led to the draining of the creek in 1852. Railroad tracks that led to and from the bustling new central train station replaced the dried creek in the 1890s and established the southern boundary of the Mill Creek community.

Next page