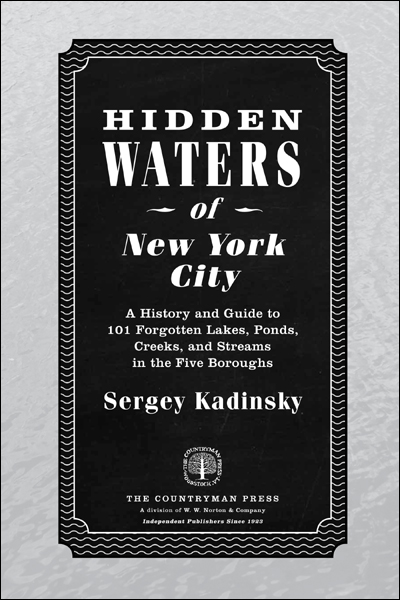

Copyright 2016 by Sergey Kadinsky

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, The Countryman Press,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please

contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com

or 800-233-4830

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

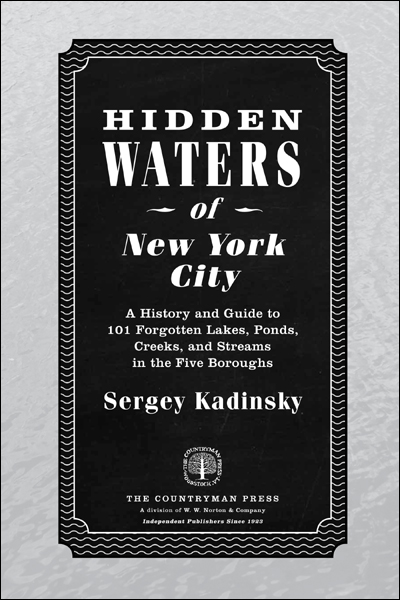

Names: Kadinsky, Sergey, author.

Title: Hidden waters of New York City : a history and guide to 101 forgotten lakes, ponds, creeks, and streams in the five boroughs / Sergey Kadinsky.

Description: Woodstock, VT : The Countryman Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015041163 | ISBN 9781581573558 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Bodies of waterNew York (State)New YorkHistory. | Bodies of waterNew York (State)New YorkGuidebooks. | New York (N.Y.)Description and travel.

Classification: LCC GB705.N7 K33 2016 | DDC 551.4809747/1dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041163

ISBN 978-1-58157-566-8 (e-book)

The Countryman Press

www.countrymanpress.com

A division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

As they before these Rivers bounds did show,

Here I come after with my Pen and row.

John Taylor (The Water Poet),

15781653

In memory of my grandfather, Zakhar Vaysbukh,

who encouraged me to inquire.

In memory of my father, Anatoliy Kadinsky,

who took me on roads not taken.

Contents

ContentsThe city of New York is built around water. Its avenues run parallel to the shorelines of the East and Hudson Rivers, while streets once extended beyond the shores as piers. Now, at the turn of the 21st century, large swaths of the formerly industrial waterfront have been transformed into parks and ferry docks. The citys waterways have become a place where the public is reminded of natures presence in the city. Examples of celebrated waterfront parks include Hudson River Park, Brooklyn Bridge Park, and Gantry Plaza State Park, with their postmodern landscaping, canoe launches, and naturalistic appearance that preserves relics of their industrial past.

Farther inland, however, waterways are not as visible, having been buried beneath streets and concealed behind buildings. If one searches carefully, one can hear sounds of hidden streams churning beneath manholes and see traces of them in street names that recall a watery past. These now-hidden urban streams provided the wampum shells used as currency by the native Lenape people, powered the gristmills of New Yorks colonial settlements, and served as freight transportation corridors during the Industrial Revolution.

As other international cities are reclaiming their hidden streams, New York, too, offers numerous examples of stream reclamation throughout its five boroughs. This book serves as a guide to the streams by tracing their historical development along their courses. Each entry follows the routes of the waterwaysalong the way documenting events, personalities, and structures associated with each stream.

Some of the hidden streams that avoided burial are now experiencing a new life as linear parks, storm water conduits, and cultural venues. Along the shores of the Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek in Brooklyn, intrepid canoe enthusiasts now ply the waterswhich are still reeking of waste but are no longer lifeless, as fish and mollusk species repopulate the channels. In Manhattan, appreciation of history is exemplified in Collect Pond Park, a one-acre green space in Manhattans Civic Center whose name commemorates a pond where many pivotal events took place in the first two centuries of the citys history. In 2012, the city began a reconstruction project that included a reflecting pool to evoke the parks namesake pond. To the northwest, Canal Street had two new parks built in the first decade of the new century that recall the long-buried namesake of this busy roadway. On Staten Island, instead of sewers, an innovative Bluebelt program repurposed the boroughs ponds and creeks as natural drainage corridors for runoff coming from nearby streets, reducing the burden for sewage treatment plants.

The citys revived streams are benefiting their surrounding communitiescontributing to increased land values, improved quality of life, and greater environmental sustainability. As in New Yorks early years as a Dutch colonial outpost, when canals served as transportation routes and ponds provided drinking water, inland waterways today have resumed their role as vital elements of the citys identity; providers of a sense of place.

Nearly all surface streams are within walking distance of public transportation, and many are located within public parks.

For streams that are buried beneath the surface, this book follows their former courses, from their sources to their mouths, describing neighborhoods and landmarks above the surface whose history is closely intertwined with the streams.

Landmarks and places of interest on or near the streams, including places no longer extant, are in bold lettering.

The island of Manhattan is as diverse in its geology as in its human population. Prior to European settlement, its waterways included kettle ponds, salt marshes, freshwater swamps, and springs that satiated the Lenape natives.

The island of Manhattan is as diverse in its geology as in its human population. Prior to European settlement, its waterways included kettle ponds, salt marshes, freshwater swamps, and springs that satiated the Lenape natives.

As the most densely developed of New York Citys five boroughs, Manhattan initially covered its inland streams, but as early as the 1850s revived them in the form of managed waterwaysfor example, in Central Park. Central Parks ponds, fed by the citys aqueduct, coexist with reservoirs that once quenched the growing citys thirst.

To the north of 125th Street, the island of Manhattan gradually narrows until it reaches its northernmost tip, at the confluence of the Harlem and Hudson Rivers. A series of ridges separate the watersheds of the East and Hudson Rivers.

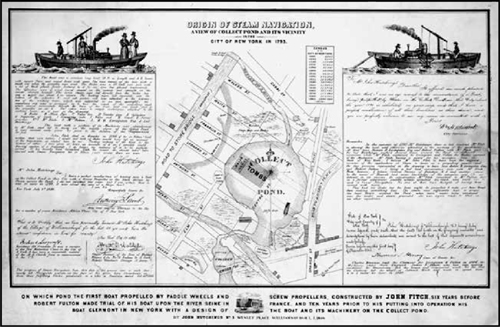

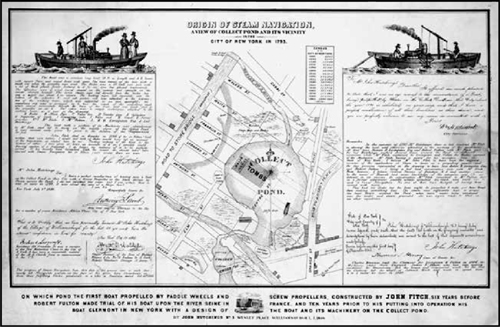

The best-documented hidden waterway in Lower Manhattan is Collect Pond, which supplied drinking water to colonial settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries. Its center and deepest point was at the present-day intersection of Leonard and Centre Streets. The pond occupied 48 acres in an outline that includes present-day Foley Square, New York City Criminal Court, New York City Department of Health, and the New York City Supreme Court. At Worth Street, a neck of land jutted into the pond, separating Little Collect from the larger section of the pond.

View of Collect Pond and its vicinity in the City of New York in 1793

Following the ponds burial in 1825, its site continued to contribute to New York Citys history as the location of the notorious Five Points slum district and the Tombs prison. In recent years, the pond has enjoyed a revival in the citys consciousness, with a reflecting pool as the centerpiece of a redesigned park that opened in 2014.

A kettle pond

When the Pleistocene period ice sheet gradually retreated north (nearly 15,000 years ago), chunks of ice that were detached from the ice cap melted on location, forming deep, kettle-shaped ponds. The 70-foot-deep Collect Pond had two outlets that drained into the Hudson River and the East River. In the event of a storm surge, these brooks would be swollen with seawater, severing Lower Manhattan from the rest of the island. Along the outflow brooks, beavers built dams to trap the alewives, sunfish, and perch that lived in the pond.

Next page

Contents

Contents The island of Manhattan is as diverse in its geology as in its human population. Prior to European settlement, its waterways included kettle ponds, salt marshes, freshwater swamps, and springs that satiated the Lenape natives.

The island of Manhattan is as diverse in its geology as in its human population. Prior to European settlement, its waterways included kettle ponds, salt marshes, freshwater swamps, and springs that satiated the Lenape natives.