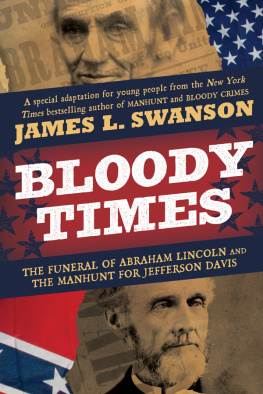

Jefferson Davis

The Man and His Hour

William C. Davis

Copyright William C. Davis 1991

The right of William C. Davis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

First published in 1991 by HarperCollins Publishers.

This edition published in 2018 by Lume Books.

For M. Jefferson Davis,

who is not named for this man

but who bears some of his finest qualities,

and for Rebecca Mahala Davis,

who would have loved the man in spite of himself

Table of Contents

Preface

Historians are sometimes a superstitious lot. It used to be said that no one who started to write a biography of Henry Clay would live through the task. Then there was the notion that those who delved too deeply into the Lincoln murder could expect unusual and sometimes sinister happenings in their own lives. And others have long believed that anyone writing a life of Jefferson Davis was only asking for trouble, for no biography of the man would ever be considered a good one.

Maybe the fault lies with the man. Even in his own time associates considered him cold, aloof, an icicle, obstinate, petty, enigmatic, vindictive, and bitter all of which he certainly was in varying measure. He was also warm, painfully sensitive to his own feelings and those of others, affectionate, witty when it suited him, very intelligent, absolutely impervious to physical fear, and loyal literally to a fault. His best side he kept hidden from all but his family and most intimate friends a circle that unfortunately excludes twentieth-century historians thus, for generations, our finest biographers have turned their talents to more sympathetic characters like Lincoln and Lee. The result is that the Davis we have been given in print has come chiefly from an unbroken string of second- and third-rate biographies, from the vituperativeness of E. A. Pollards to the cloying worshipfulness of Hudson Strodes and the antiseptic brevity of Clement Eatons.

Maybe the fault lies with the historians, who have so consistently baffled themselves by approaching Davis as if he were a molded icon who somehow, when cooled, failed to match the cast. The Sphinx of the Confederacy, they have called him, an enigma, a mystery, and more. Historians have consistently failed to look on him as they would on other men. Instead they have seen only a man of great attainments, thrust into a great position, who failed to act like a great man. Frustrated by this, they have decided that he is an insoluble mystery. Yet there is nothing at all mysterious about Jefferson Davis. We have all known him in bits and pieces of ourselves and others in our lives, and it asks little more than a good grasp of human nature to come to grips with the man.

Perhaps no one is at fault. Some figures of the past and the present defy good biography. By their character or temperament, or the times in which they live, they leave a record that simply cannot be interpreted satisfactorily in fairness and justice to the subject and the reader. What Davis is to the biographers of today, Richard Nixon may be to those of the next century. Both were complex men whose roles in turbulent times seem to defy adequate delineation.

Whatever the cause, biographies of Jefferson Davis never seem to give universal pleasure, and undoubtedly this one will not prove an exception. Sheer volume will have something to do with that, for this is a massive book, a lot to read for most people whose only knowledge of Davis is the vague notion that they will dislike him. Those who nevertheless essay the task are entitled to a few words of explanation about some aspects of what they undertake.

Some will perceive what seems to be an imbalance of coverage. Nearly a third of the book deals with his life up to 1861; half is devoted to the next four years; then a fraction covers his remaining twenty-four years. Moreover, his childhood and early youth receive more attention than do substantial portions of his senatorial career. His Mexican War service occupied more ground than did his role in the crisis of 1860, while in the chapters on the Civil War years, his first eighteen months as president of the Confederacy get almost as much space as does the balance of his tenure. Meanwhile, his oft-vaunted service as secretary of war in 1853-57 is passed over rather speedily.

It is all a matter of perspective. The fact is that there is one reason, and only one, for writing or reading a biography of Jefferson Davis, and that is his quadrennium as leader of the Lost Cause. Without this vital element, few if any Americans would ever have heard of him, or wanted to. Who remembers any of the secretaries of war prior to World War II? How many of the hundreds of senators and congressmen who have served in the past two centuries are truly worthy of biographies? Davis created no significant legislation, and even in the march to secession he played a secondary role. His years in the war office generated nothing we remember or care about today, other than vaguely held notions that he tried a seemingly whimsical experiment with camels. As for his postwar years, once he left prison there was nothing to set his life apart from those of the hundreds of thousands of other former Confederates trying to rebuild their lives nothing but the fact that he had been their president.

In short, nothing in this mans life would attract more attention than a thesis or dissertation had he not been chosen to take an oath in Montgomery, Alabama, in February 1861. Thus the preponderance of this biography looks at the four years that followed that oath. As for his prewar life, it is chiefly important only for what it reveals of the making of the president in 1861 how his attitudes and values developed and how his character took shape in the fashion that left such a distinctive mark on the Confederacy. It is for this reason that his early years are so important, including the West Point and Mexican War days that distinctively influenced his thinking on military matters. As for his senatorial career, much less space could actually have been devoted to it, for once his ideas and opinions took shape in the 1840s, they rarely if ever changed. Indeed, the balance of his political career in the old Union was little more than a constant repetition of those ideas. And as for the opposite end of his life, his years after 1865 have little value outside the contexts of Daviss reflections on the war and of his symbolic role as a leader of the Old South embarking into a new one. In the Civil War years themselves, meanwhile, the first eighteen months reveal the development of Davis to the highest point he achieved as a chief executive. By the end of 1862, the decisions, the strategies, the appointments, and the loyalties and antipathies by which he would conduct the balance of the conflict had been set in place.

This book is a life, not a life-and-times. Already substantial, it would be much more so if extensive background were interwoven on every political contest, every campaign or battle, and each of his many personal feuds. Enough has been provided to illuminate either Daviss direct participation or his influence. Similarly, his remarkable wife Varina Howell Davis does not spend much time at center stage. By any measure she was an unusual individual, very much a twentieth-century woman. But thanks to the limitations of the era in which she lived, she remains important to us today for no reason other than the fact that marriage changed her name to Davis. She exerted considerable influence on him at times, for good and ill. Moreover, as first lady of the Confederacy she shared with him as no other the burdens of his responsibility, and to the extent that she had an impact on her husband she appears here. This unusual woman deserves serious study in her own right.

Next page