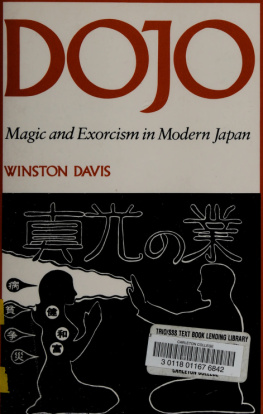

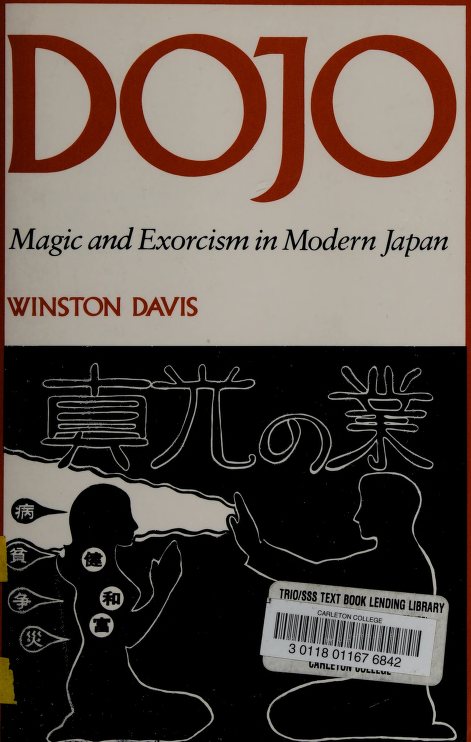

Dojo : magic and exorcism in modern Japan

Pages

Dojo : magic and exorcism in modern Japan

Davis, Winston, 1939

This book was produced in EPUB format by the Internet Archive.

The book pages were scanned and converted to EPUB format automatically. This process relies on optical character recognition, and is somewhat susceptible to errors. The book may not offer the correct reading sequence, and there may be weird characters, non-words, and incorrect guesses at structure. Some page numbers and headers or footers may remain from the scanned page. The process which identifies images might have found stray marks on the page which are not actually images from the book. The hidden page numbering which may be available to your ereader corresponds to the numbered pages in the print edition, but is not an exact match; page numbers will increment at the same rate as the corresponding print edition, but we may have started numbering before the print book's visible page numbers. The Internet Archive is working to improve the scanning process and resulting books, but in the meantime, we hope that this book will be useful to you.

The Internet Archive was founded in 1996 to build an Internet library and to promote universal access to all knowledge. The Archive's purposes include offering permanent access for researchers, historians, scholars, people with disabilities, and the general public to historical collections that exist in digital format. The Internet Archive includes texts, audio, moving images, and software as well as archived web pages, and provides specialized services for information access for the blind and other persons with disabilities.

Created with abbyy2epub (v.1.7.6)

3 011801167

bHriLc i un

D0]0

Magic and Exorcism in Modern Japan

WINSTON DAVIS

Magic and Exorcism in Modern Japan

DOJO

Magic and Exorcism in Modern Japan

WINSTON DAVIS

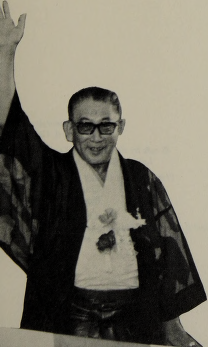

OVERLEAF

Okada Kotama, founder of Sukyd Mabikari

Stanford University Press Stanford, California

1980 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University

Printed in the United States of America Cloth isbn 0-8047-1053-8 Paper isbn 0-8047-1131-3

Original printing 1980 Last figure below indicates year of this printing: 01 00 99 98 97 96 93 94 93 92

For linda and colin who shared the adventure and

for MONICA

who will share others

In March 1976 I went to Japan with my family to study Shinto festival organizations. While there, I accidentally came upon an exorcistic group called the True-Light Supra-Religious Organization. Known as Sukyo Mahikari in Japanese, this sect turned out to be the most primitive religious community I had ever encountered in Japan. Although primitive may be too strong a word to use, it does express my immediate reaction to the group, its ideas and practices. The only thing that had prepared me for this experience was some work I had done on African magic and witchcraft as a graduate student at the University of Chicago.

I found little in Mahikari that I could empathize with personally. Its belief in spirit possession, its idea that medicine is poison, its latent ethnocentrism and manifest occultism, taxed patience and scholarly objectivity alike. I must therefore admit that this book has grown out of a prolonged reflection on my own culture shock. Although professionally trained in the history of religions, I found myself asking again the simplest and most fundamental questions about religious experience. How is religion possible? What are the motivations, needs, satisfactions, meanings, and mechanisms that have enabled religions like Mahikari to come into existence and even thrive? How do such groups put together and sustain worldviews that, in so many respects, run against the grain of contemporary Japanese culture?

Madame de Staels tout comprendre cest tout pardonner is

Preface

viii

too demanding a rule to impose on realistic students of religion and society. More appropriate is the advice of Charles Dickens Mr. Sleary: I conthider that I lay down the philothophy of the thubject when I thay to you, Thquire, make the betht of uth: not the wurtht! Although I could not always appreciate the ideas and practices of the religion, I have tried to keep Mr. Slearys words in mind. Since some readers will find my presentation of Mahikari odd, a bit droll, or perhaps even repugnant, I must insist that I have at least tried to make the betht of the followers of the religion. When compelled to present material that is at odds with Western sensibilities, I have sought to do so charitably, or at least sans commentaire. In my concluding chapter I suggest that more important than the good and bad of the religion itself is the question of the rationality of the society that gave it birth.

Today, a liberal suspension of disbelief is becoming de rigueur in religious studies. But this approach, and the Im OK; youre OK attitude it seems to entail, may not be the most authentic or productive way to understand a foreign religion. It is my opinion that one can understand a religion without believing in it, practicing it, or even appreciating it. In fact, I would go so far as to say that belief, practice, and appreciation have nothing whatsoever to do with understanding a religion. Some of the conclusions I have reached in this book would have been impossible, or at least unlikely, were it not for the luxurious distance that disbelief alone could afford. Because Mahikari does not use the word believer, I could legitimately call myself a member (kamikumite) without committing myself to anything in particular. I was perfectly open with members about my motives for joining the church. Most members, in turn, seemed quite satisfied that I had joined for no better reason than to do research. The leaders of the local church graciously enabled me to participate in the life of the group without making any profession of faith. Since Mahikaris founder had vented his wrath on philosophers but not on sociologists, my role in the church was relatively secure.

Unlike some accounts of popular Japanese religion, this book is not based on the philosophical account that leaders of the New Religions are wont to give to foreign visitors. Rather, it presents the Mahikari gospel as it is preached, believed, and practiced in a

IX

provincial congregation of unpretentious common people. Nakayama City may not have been the best place to study Mahikari.* In Tokyo there is a much richer oral tradition about the deeds and sayings of the founder, Okada Kdtama. Because the headquarters of the church were still in the capital at the time I was doing my research, I would probably have been able to say much more about the national organization had I done my work there. On the other hand, working in a relatively remote place like Nakayama had its own rewards. Because Nakayama is still relatively provincial, many members of the local church are deeply rooted in the folk tradition from which the gospel arose. Being this close to the grass roots turned out to add not just local color, but real depth to my study.

Understanding a foreign culture presupposes both empathy and genuine distance. Simply putting that culture into the categories of ones own civilization inevitably causes distortion and misunderstanding. On the other hand, all goodwill and objectivity notwithstanding, it is also impossible to understand a foreign culture simply by introducing it into our thought world on its own terms. Introjection is not the same as interpretation. Understanding an alien culture or religion always involves an untidy compromise between three very different languages. First, there is the language spoken by ones informants, sometimes called emic discourse by anthropologists. Then there is the language of scholarship, or the etic categories and distinctions that we superimpose upon what the natives say. And finally, there is the language of the researcher himself, in my case English. Because the values and religious traditions of a society always have repercussions in language, the idiosyncrasies of ones mother tongue are of crucial importance when trying to interpret another culture.

Next page