ABOUT TUTTLE

Books to Span the East and West

Our core mission at Tuttle Publishing is to create books which bring people together one page at a time. Tuttle was founded in 1832 in the small New England town of Rutland, Vermont (USA). Our fundamental values remain as strong today as they were thento publish best-in-class books informing the English-speaking world about the countries and peoples of Asia. The world has become a smaller place today and Asias economic, cultural and political influence has expanded, yet the need for meaningful dialogue and information about this diverse region has never been greater. Since 1948, Tuttle has been a leader in publishing books on the cultures, arts, cuisines, languages and literatures of Asia. Our authors and photographers have won numerous awards and Tuttle has published thousands of books on subjects ranging from martial arts to paper crafts. We welcome you to explore the wealth of information available on Asia at www.tuttlepublishing.com .

AFTERWORD

Since this book evolved out of a specific approach to teaching Japanese cultural history at a number of universities in Japan, it is perhaps appropriate to conclude with some comments on the state of history teaching in our schools in general today. It is said that a knowledge of history brings perspective and proportion; yet perspective and proportion are all too often missing in the current debate on how history should be taught in our education systems. History has always been a controversial and contentious subject, but these days, it is often so politically toxic that no one seems to want to touch it. At best, in most schools, it usually involves the rote memorization of disconnected dates, figures, and events for regurgitation on state-sponsored examinations, leaving little scope for the kind of overarching perspective needed to provide an adequate understanding among learners.

In contrast, the approach used in this book is based on the development of a conceptual framework, the multilayered model, which provides the infrastructure necessary for a broad understanding of Japanese cultural history. It is important to note here that a model is an abstract representation of reality. The two key words in this definition are abstract and representation . A model is not supposed to be exactly like reality. Rather, it represents the real world by abstracting , or taking from it, that which will help us understand it. There is much in the real world that a model must leave out. When building a model, how can one know which details to include and which to leave aside? There is no simple answer to this question. The right amount of detail depends on ones purpose in building the model in the first place, but in most cases, keeping a model simple makes it easier to see basic, underlying principles at work.

In the case of the multilayered model used in Japanese Culture: The Religious and Philosophical Foundations , the descriptions of each layer, taken separately, necessarily leave much out. Yet, when combined into a cohesive whole, this conceptual framework provides an overview of Japanese cultural history that is simple, elegant, and easy to understand. It is hoped that this clarity and scope of vision will provide readers with a useful starting point for their own further explorations of this complex and fascinating culture.

APPENDIX A

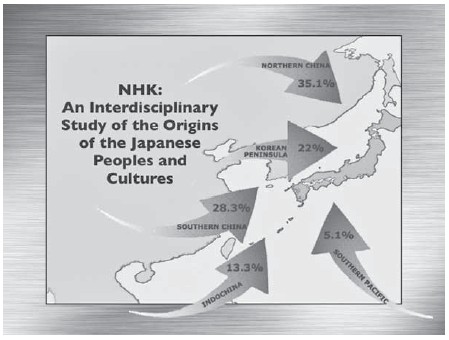

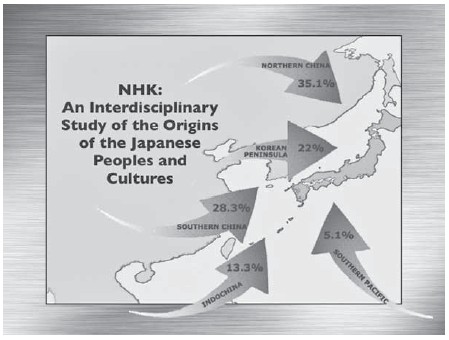

ORIGINS OF THE JAPANESE

APPENDIX B

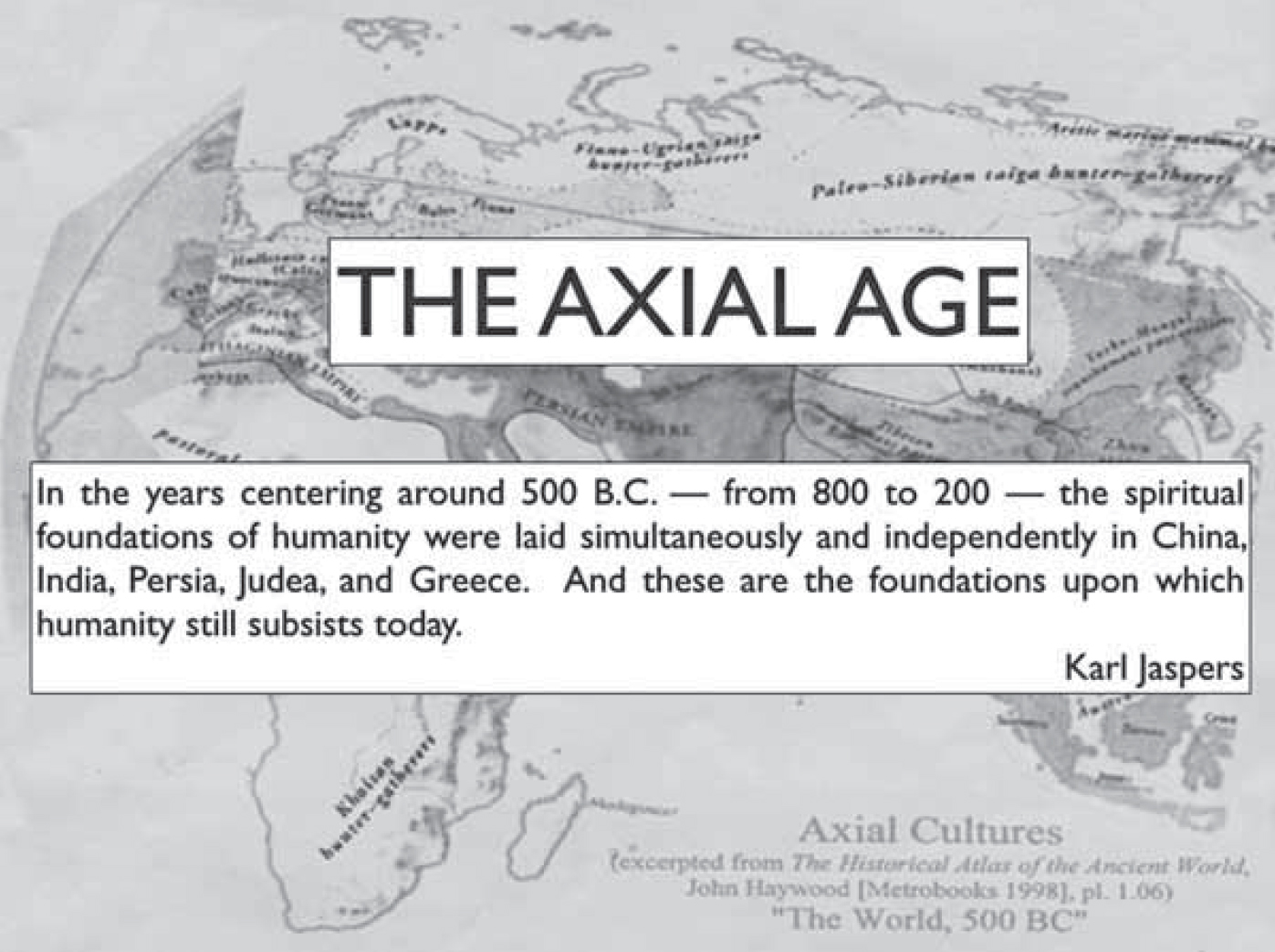

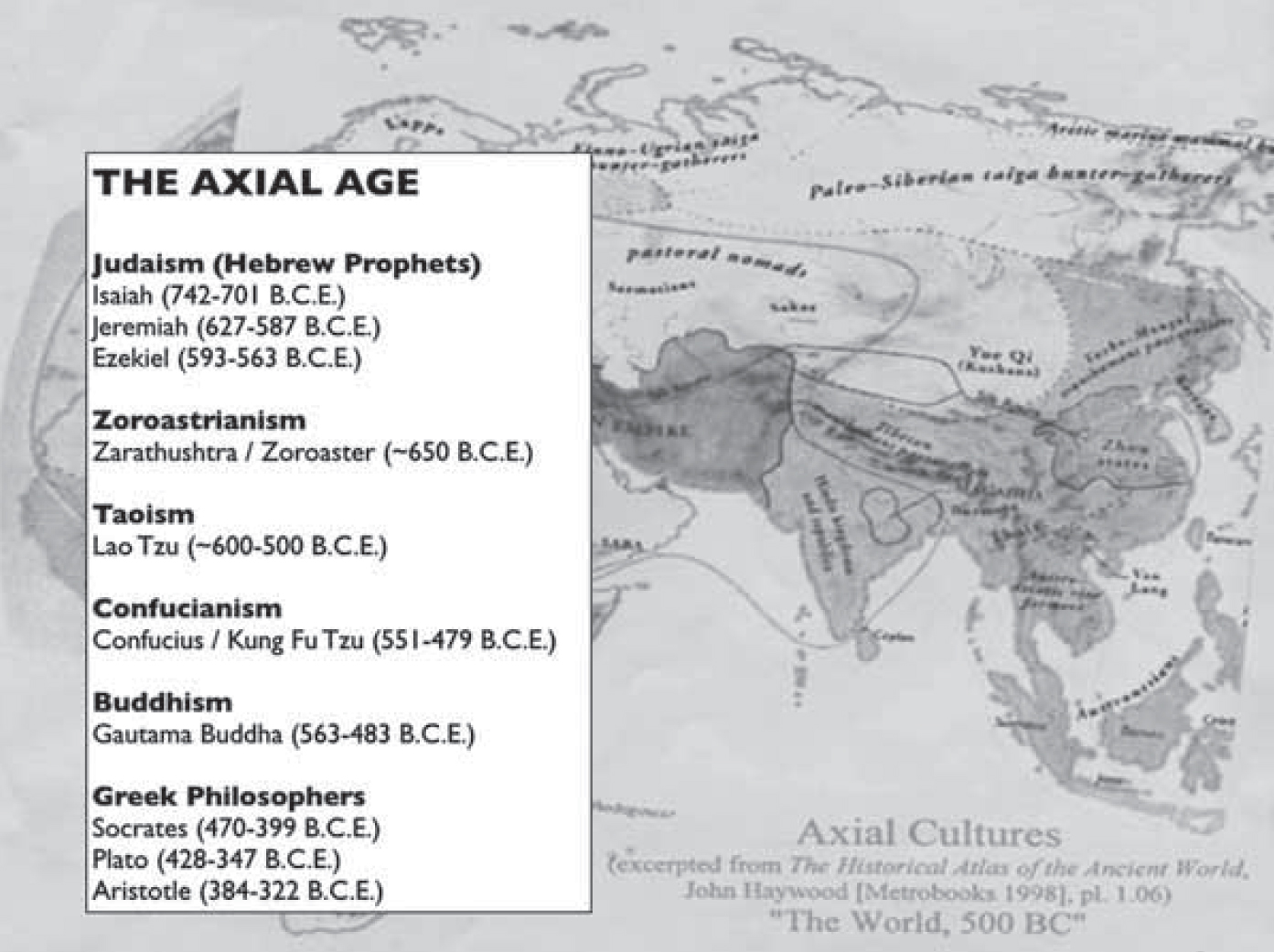

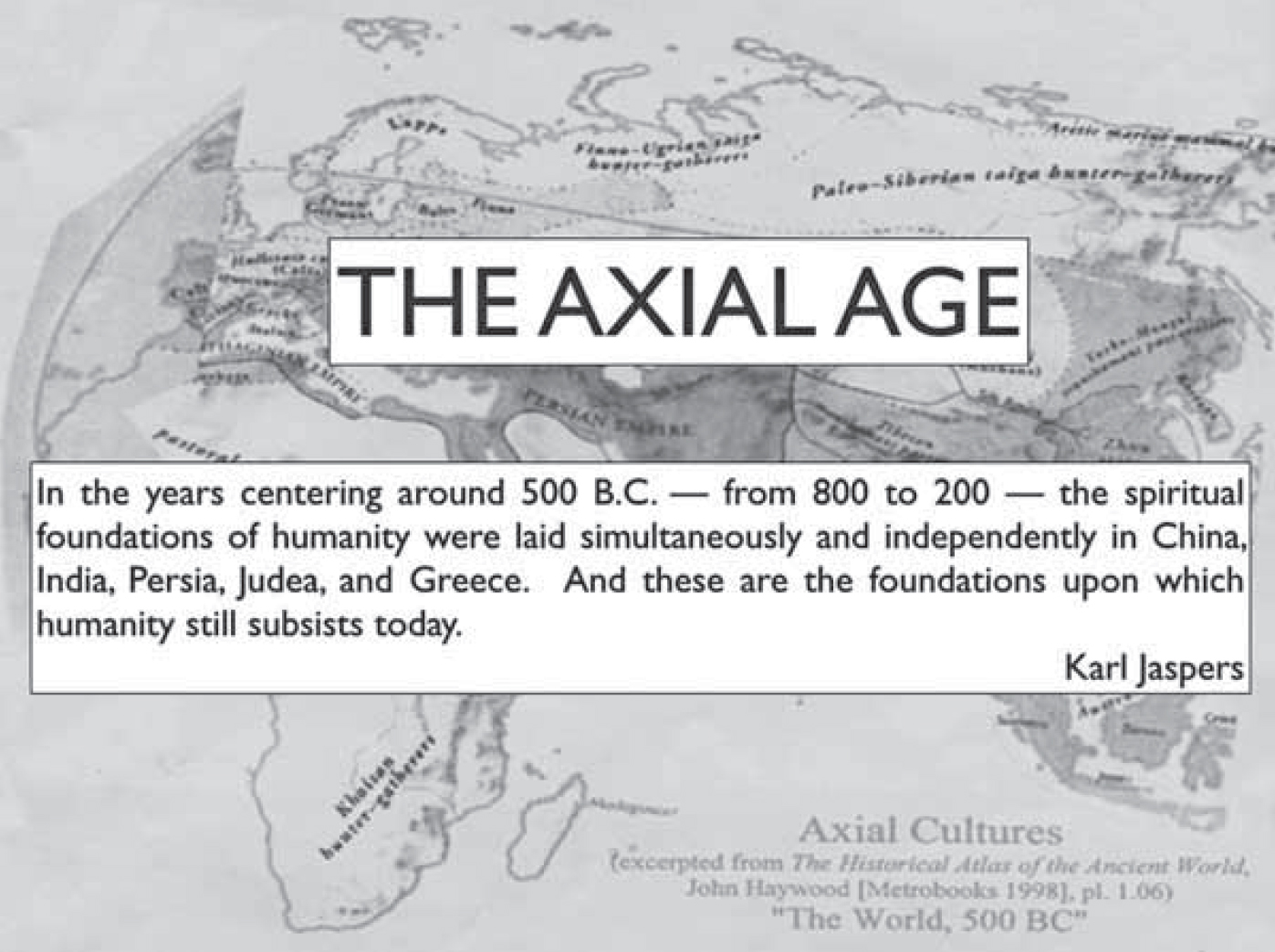

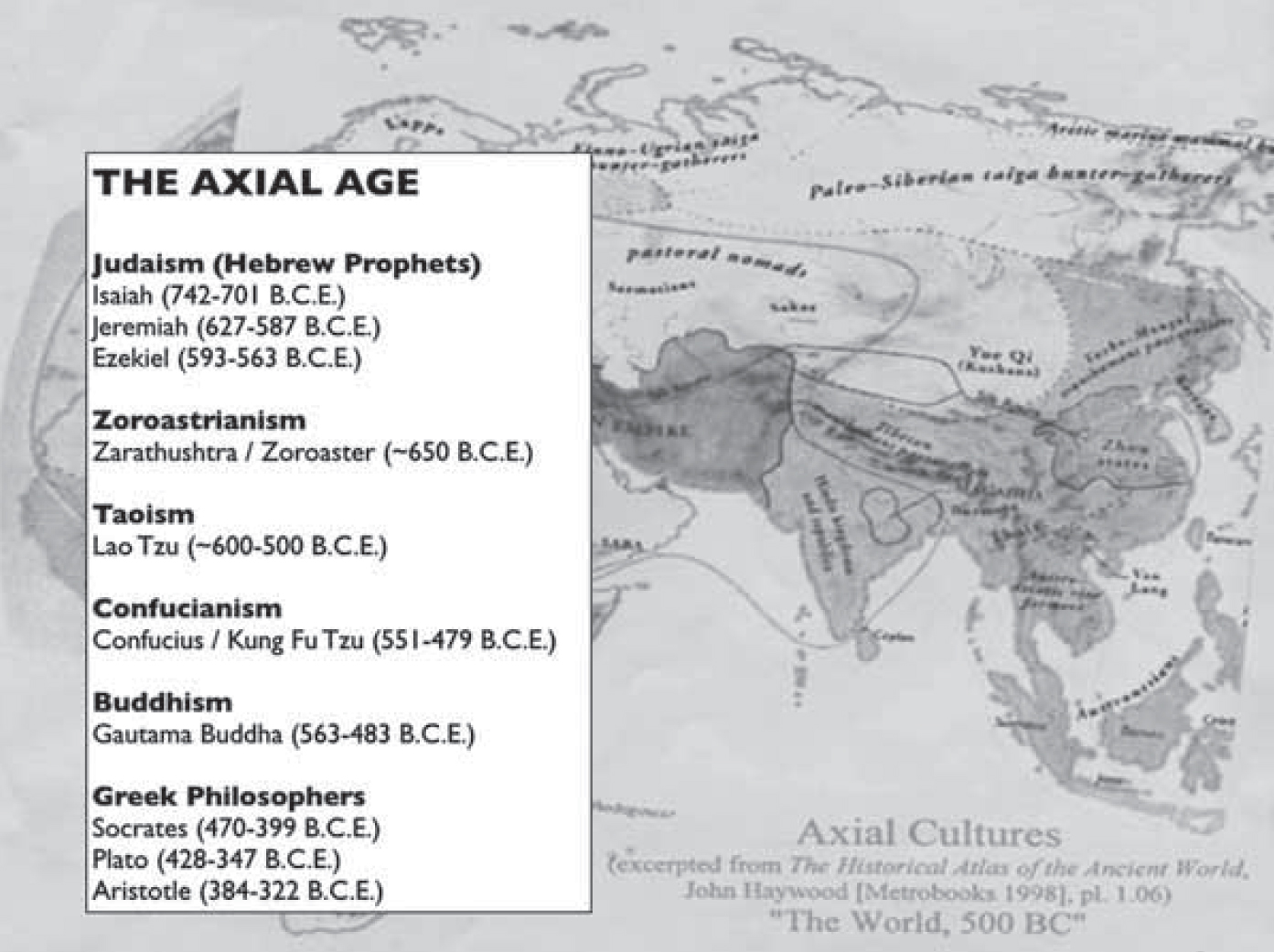

THE AXIAL AGE

THE AXIAL AGE

[adapted from Cahills Desire of the Everlasting Hills , 1999, pp. ]

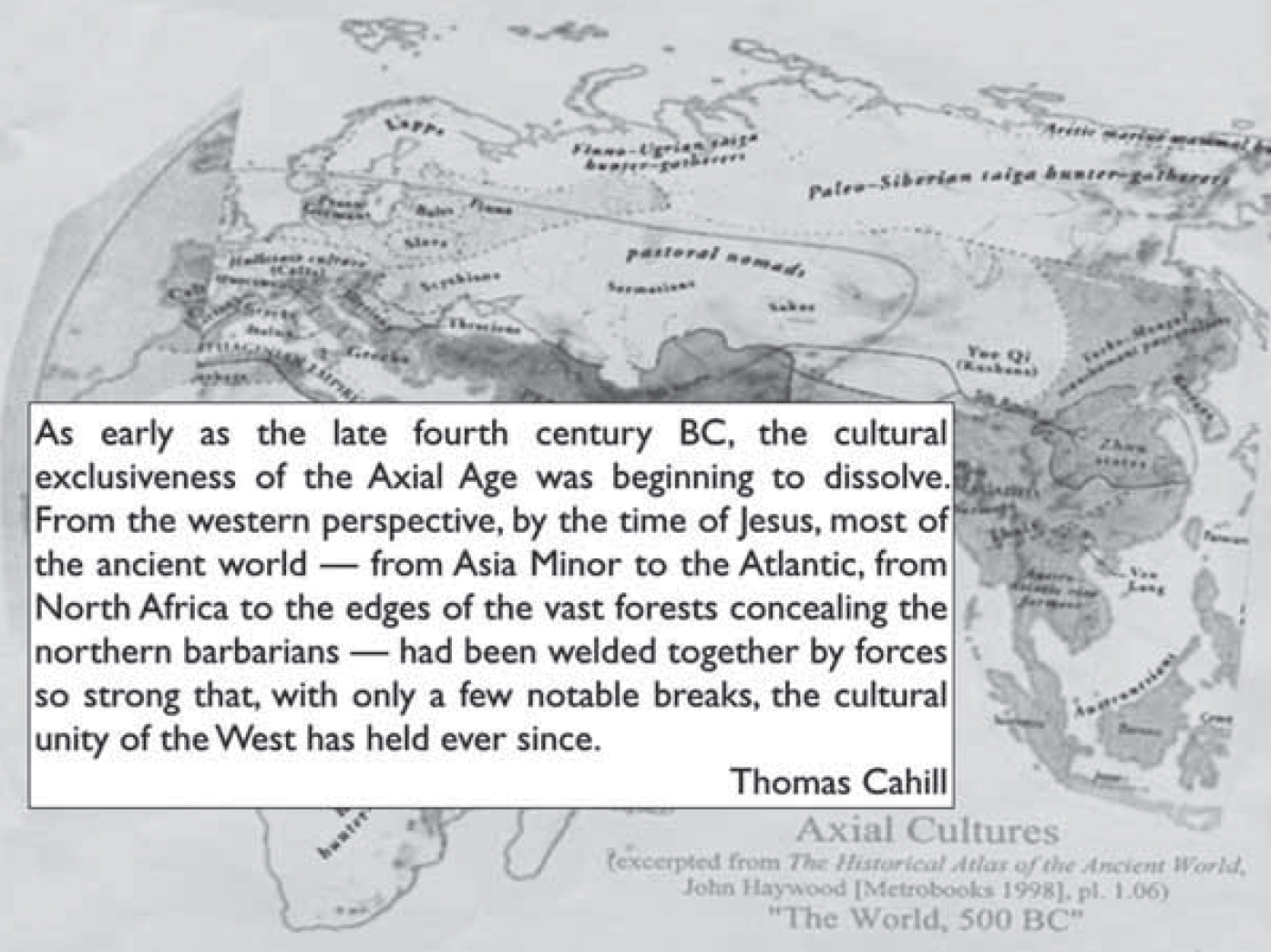

The Axial Age lasted some 300 yearsfrom the late seventh century BC to the late fourth. In Confucian China, it witnessed the development of reasonableness and courtly moderation, as well as the mysticism of the Tao of Lao-Tzu. In India, the Axial Age produced Gautama Buddha, who reformed the chaos of more ancient religious systems and revealed the steps to personal peace. In Iran, the priest Zarathustra taught the Persians the Zoroastrian vision of a cosmic battle between good and evil. To the west, in the tiny kingdoms of Israel and Judah, the Hebrew prophets arose, giving to the monotheism of their people an ethical foundation so profound that it has been the mainstay of the Jewish faith ever since. In the islands and peninsulas of Greece, the Axial Age saw the flowering of what would come to be called philosophythe love of wisdom for its own sakeand of a noble form of politics called democracy ( demos = the people).

All of these ancient civilizations showed distinct similarities to one anotherthey developed literacy, complex political organizations, elaborate town-planning, advanced metal technologies, and the practice of international diplomacy. During the Axial Age, in all of these cultures, there was a profound tension between political powers and intellectual movements, resulting in attempts everywhere to introduce greater purity, greater justice, greater perfection, and a more universal explanation of things. At this time in the world, new models of reality, either mystical or prophetic or rational, arose as a criticism of, and alternative to, prevailing models.

But these cultural developments proceeded in parallelthey never intersected and never influenced one another except in the most marginal ways. As a result, the world that existed at the beginning of the third century BC was still a world of separate societies, each enclosed by its own characteristic language and values, each with its own Golden Age to look back on, each populated by its own heroes. In the mind of a third-century Athenian, for example, the memory of philosophers such as Socrates and Plato was still strong, and he bore the standards of excellence established by these men within him for reference and judgment. He knew nothing of Abraham and Moses, the figures who lived in the mind of every inhabitant of third-century Jerusalem, just a few miles to the east across the Mediterranean Sea.

As early as the late fourth century BC, this cultural exclusiveness was beginning to dissolve, however. From the western perspective, by the time of Jesus, most of the ancient worldfrom Asia Minor to the Atlantic, from North Africa to the edges of the vast forests concealing the northern barbarianshad been welded together by forces so strong that, with only a few notable breaks, the cultural unity of the West has held ever since.

APPENDIX C

THE MULTILAYERED MODEL OF JAPANESE CULTURE

APPENDIX D

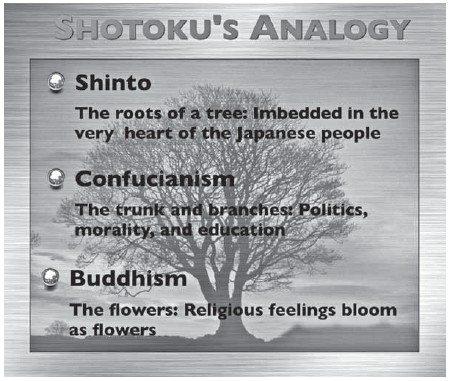

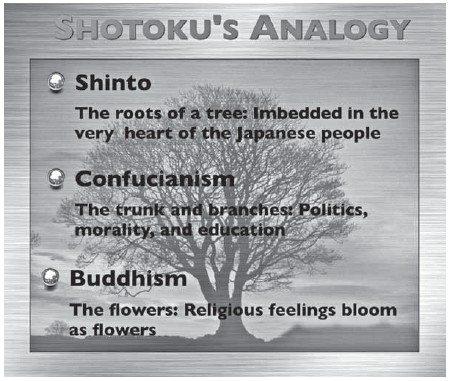

SHOTOKUS ANALOGY

APPENDIX E

SHINTO SHRINES ILLUSTRATED

The most outstanding architectural characteristic of Shinto shrines is the simplicity of their construction and ornamentation. Ise Shrine, which is rebuilt in exact replica every twenty years, is considered the purest and most ancient style of Japanese architecture.

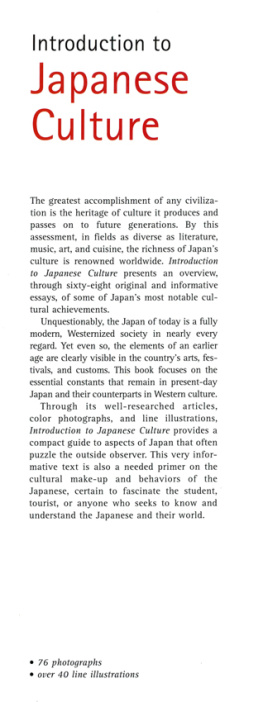

Next page