Map 1. The Appomattox Campaign, April 19, 1865

Map 2. April 15, 1865

Map 3. April 57, 1865

Map 4. Sailors Creek, High Bridge, and Cumberland Church

Map 5. April 89, 1865

Map 6. Appomattox Court House and Appomattox Station

Foreword

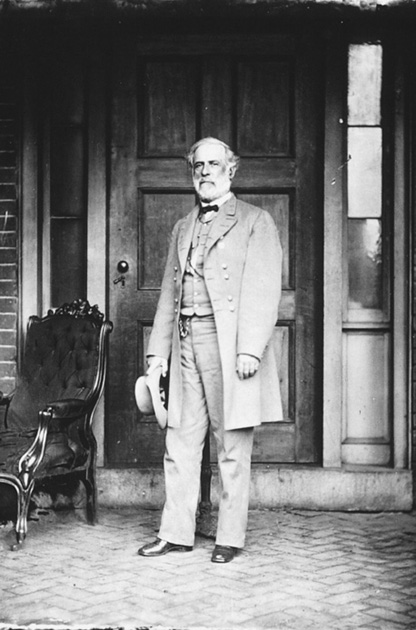

In our youth we came to know of a crossroads village in the Virginia countryside called Appomattox Court House. To this place came the tattered, starving, but irrepressibly devoted remnant of Robert E. Lees Confederate army, skeleton-thin from battle and closely pursued by vast hordes of well-fed, meticulously equipped Federals. Here they found themselves hopelessly surrounded through no fault of their beloved commander, who surrendered them rather than sacrifice their livesaccepting that responsibility with quiet resolve and unruffled dignity. At the moment of his surrender, sectional differences dissolved. The victors and vanquished mingled in fraternal camaraderie; the Northerner forgave the Southerner for his treason, and the Rebel reconciled himself to reunion, satisfied to have fought the good fight. Their sojourn at Appomattox culminated in a surrender ceremony perpetuating that spirit of mutual regard, with the erstwhile opponents exchanging snappy salutes as the Confederates marched in to stack their weapons.

We who greeted the Civil War centennial with the impressionable enthusiasm of adolescence know this story well, as did our grandfathers before us, yet each element of the tale defies the surviving contemporary evidence. During the final week of the war in Virginia the troops under Lee proved more numerous and far less faithful to their cause than they have been portrayed: for every Confederate who was killed or wounded between Petersburg and the Piedmont, several others discarded their weapons in despair, gave themselves up, or simply walked away. Though still a foe to be reckoned with, General Lee proved less than infallible in his last campaign, and defeat wrung from him an unusual display of defensive faultfinding. The congenial intermingling of the armies at Appomattox is shamelessly overblown, and the renowned exchange of salutes appears to have sprung belatedly from the imaginations of a pair of generals well practiced in the art of fabricating popular legends.

Few epochs in American history have become the targets of such deliberate mythmaking as the Civil War, and no episode of that war (perhaps not even Gettysburg) has been so particularly afflicted as the retreat that ended at Appomattox. Lee had no sooner left the McLean house than the remolding of history began with speeches from men like John B. Gordon, who would never abandon the campaign to have his own way with the past. Partisan Southern historians rallied immediately to the Lost Cause, creating a romance in which the valiant Confederate soldier had been vanquished through no fault of his own by forces far beyond his control. Disasters resulting from organizational and administrative shortcomings within the army were laid at the door of the hated bureaucrat; battlefield defeats were attributed to the sheer number of the enemy. Confederate apologists ignored the widespread desertion that characterized the retreat, or deliberately disguised its extent, instead implying that combat losses and starvation-induced physical debility accounted for the gaps in Lees attenuated line of battle at Appomattox.

The guns had lain silent for only a year before the first major work of revisionist Southern history appeared from the pen of Edward A. Pollard. An ardent young Confederate who avoided field service throughout the conflict, Pollard manipulated and invented statistics to demonstrate that Northern might ought to have crushed Lees army long before Appomattox, had it not been for Confederate courage and tenacity. His history of the war echoed with references to Grants overwhelming forces, overwhelming numbers, and a match of brute force. He quoted one source that claimed, It is said of these devoted men who yet clung to the great Confederate commander, that their suffering from the pangs of hunger has not been approached in the military annals of the last fifty years, and he alluded with what would become a traditional particularity to an army that by April 9 had dwindled down to eight thousand men with muskets in their hands. Although Pollard acknowledged the presence of thousands of Confederate stragglers on that last day, he excused them as famishing and too weak to carry their muskets.

A decade after the war ended, this theme of heroic struggle against impossible odds dominated Southern lore, and nothing seemed to substantiate the theme better than the final clash at Appomattox: the 8,000 muskets arrayed against 80,000, 100,000, or even 200,000; the deserters and skulkers forgiven on the grounds of starvation; the errors of the campaign forgotten. In June of 1876 former lieutenant general Jubal Early complained that the Federal authorities and Federal writers have almost invariably exaggerated our strength, and the papers of the Southern Historical Society provided an opportunity to reverse that trend with a vengeance. The society had not been publishing for a full year before Lost Cause proponents embraced it as a medium for inflating the odds Lee faced at Appomattox. Always the emphasis swung to the number of muskets, rather than to the number of Confederates; that eliminated the need to consider several thousand more cavalry and artillery, and it especially avoided the thorny question of the unarmed mob that equaled or exceeded the fighting force.

Then came Northern revisionism, as a new spirit of nationalism erased sectional differences in the 1890sand especially after the Spanish-American War. Brotherhood and mutual respect formed the principle element of this school of American history, and stories told three decades after the war tended to soften the undercurrent of antagonism that had previously characterized the written record. Just into the new century, Joshua Chamberlain supplied his most polished version of a moving Appomattox fable that involved promoting himself to command of the surrender ceremony and ordering his men to salute the defeated Confederates as they marched in to give up their arms. Readers below the Mason-Dixon Line loved this retroactive deference to Southern arms, however embellished it might have been; they adopted it as their own, republishing it in the Southern Historical Society Papers