Appomattox

Appomattox

Victory, Defeat, and Freedom

at the End of the Civil War

ELIZABETH R. VARON

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Elizabeth R. Varon 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Varon, Elizabeth R., 1963

Appomattox: victory, defeat, and freedom at the end of the Civil War / Elizabeth R. Varon.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-975171-6 (hardback)

1. Appomattox Campaign, 1865.

2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Peace.

3. Lee, Robert E. (Robert Edward), 18071870.

4. Grant, Ulysses S. (Ulysses Simpson), 18221885.

5. Reconstruction (U.S. history, 18651877) I. Title.

E477.67.V37 2013

973.738dc23 2013019903

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

CONTENTS

This project has its origins in an invitation I received in 2009 to speak on the subject of Juneteenth at the Library Company of Philadelphia; in the course of researching emancipation day celebrations, I learned of the centrality of Lees surrender in postwar discourse on black liberation, and I began to see Appomattox in a new light. Given my long-standing fascination with Grant and Lee, I was eager to connect my new knowledge to my old interests. I thank my friend Julie Campbell at Washington & Lee University for joining me on a memorable outing to Appomattox for some early field research and for encouraging me to write this book. I am grateful for the chance I had to workshop my preliminary findings at colloquia at Princeton University and Georgetown University. And I thank my research assistant at Temple University, Dr. Zachary Lechner.

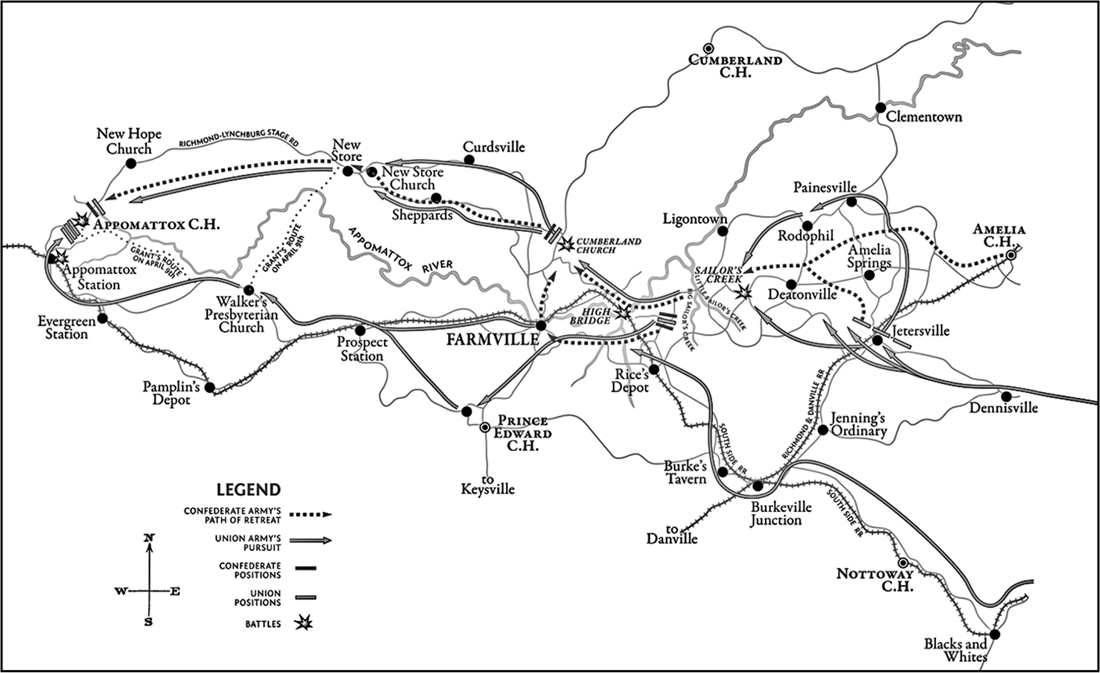

A stroke of good fortune brought me home to Virginia in the fall of 2010 and kicked the project into high gear. I benefited immensely from the expertise and generosity of three historians in particular: Christopher Calkins at Sailors Creek Battlefield Historical State Park; Patrick Schroeder at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park; and John Coski at the Museum of the Confederacy. I found countless treasures at the Library of Virginia, the Virginia Historical Society, and special collections at Washington & Lee University, and I thank the staffs of these splendid institutions for their assistance.

Most especially, I am grateful for the resources of the University of Virginia: the vast Civil War holdings at Alderman Library and Small Special Collections; the research support of the College of Arts and Sciences; the example set by my colleagues in the Corcoran Department of History; the energy of my research assistants Jon Grinspan and Eric Sargent; and the friendship and wisdom of Gary Gallagher, who was kind enough to read my manuscript and share his singular command of the Civil War era. I am also grateful to the History Departments at Chestnut Hill College and George Mason University, and to the Society of Civil War Historians, for providing forums in which I could test my conclusions.

Susan Ferber at Oxford University Press brought her editorial expertise and deep knowledge of the field of nineteenth-century U.S. history to bear on the manuscript, rendering it more cogent and readable; the anonymous readers she chose for the manuscripts final vetting made many excellent suggestions for revisions.

I thank my husband, Will Hitchcock, for his unflagging support and enthusiasm; for his many insights on the historical themes of victory, defeat, and liberation; and for his skillful tweaking of some key passages in this book. I have drawn energy, as ever, from my fathers abiding faith in the future. His ability to radiate love is at once humbling and inspiring. My brother and fellow historian Jeremy knows this better than anyone and knows, too, how much I treasure our sixth-sense sibling bond.

Most of all, I am grateful to my children, Ben and Emma, for the light and laughter, the sweetness and solidarity, they bring to our every day. This book is for them.

E.R.V.

Charlottesville, Virginia

Appomattox

On Palm Sunday, April 9, 1865, Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of the Union army, met Robert E. Lee, his Confederate counterpart, in the modest parlor of Wilmer McLean, in the Southside Virginia village of Appomattox Court House. Lee was the very picture of dignitywearing a solemn expression and fine dress uniform, he embodied the proud gentility of the Souths planter elite. Grant, dressed casually in a mud-spattered uniform, embodied a dignity of an altogether different sort: that of the hardscrabble farmers and wage earners he had molded into a formidable fighting machine. After awkwardly exchanging some pleasantries about their service in the Mexican War, the two men agreed to the surrender terms that effectively ended the Civil War. In essence, Grants terms set free the conquered soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia, on the promise that they would never again take up arms against the United States. Grants magnanimity in this hour, and Lees stoic resignation in defeat, inaugurated a process of national healing that would not only restore the shattered Union but would also prepare the way for Americas emergence as a world power.

This scene forms one of the most significant moments in the story Americans tell themselves about the meaning and legacy of the Civil War. Unfortunately, it is a myth. Grant and Lee did meet at Appomattox and sign the surrender terms in McLeans parlor. But the meaning of this event has never been fully understood. As Grant and Lee set their hands to the surrender terms, they positioned themselves at the center of a bitter and protracted contest over what exactly was decided that April day at Appomattox. The two men represented competing visions of the peace. For Grant, the Union victory was one of right over wrong. He believed that his magnanimity, no less than his victory, vindicated free society and the Unions way of war. Grants eyes were on the futurea future in which Southerners, chastened and repentant, would join their Northern brethren in the march towards moral and material progress. Lee, by contrast, believed that the Union victory was one of might over right. In his view, Southerners had nothing to repent of and had survived the war with their honor and principles intact. He was intent on restorationon turning the clock back, as much as possible, to the days when Virginia led the nation and before sectional extremism alienated the North from South.

Next page