First published in 1945 by Methuen & Co. Ltd.

This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1945 Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN: a46000842

ISBN 13:978-1-138-55152-7(hbk)

ISBN 13:978-0-203-70454-7(ebk)

THE LYONS MAIL

THE LYONS MAIL

being an account of the crime of April 27

1796 (Floral 8 an IV) and of the trials

which followed

A study of personalities and of

evidence, as also of judicial procedure,

under the First French Republic

BY

CHARLES OMAN

CHICHELE PROFESSOR OF MODERN HISTORY

IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

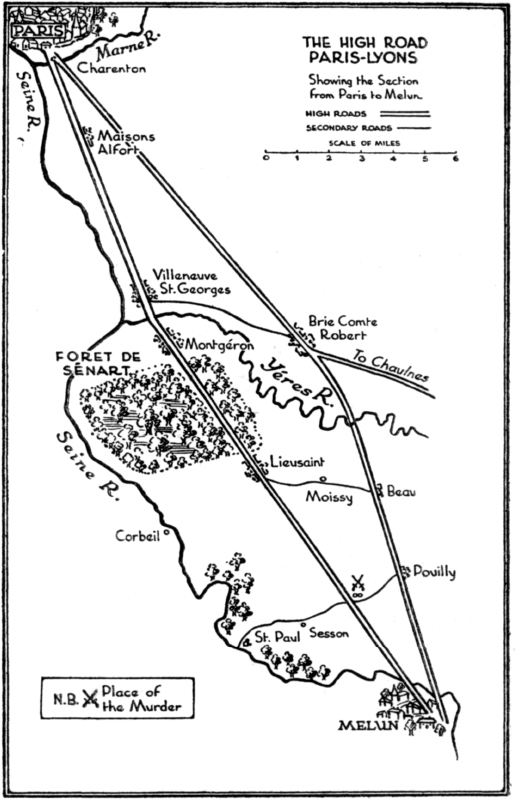

WITH THREE ILLUSTRATIONS

AND A MAP

First published in 1945

HISTORY has many unexploited corners. I have devoted the enforced and austere leisure of four years of war to such useful work as was possible for one of my advanced agehelping to keep the University machine grinding on at low pressureand compiling an analysis of the Hundredal arrangements of Domesday Book. But in the fifth year I found myself yearning to turn aside for a moment to a small and definite piece of historical investigation, as far as possible from Hundreds and Wapentakes, and full of personal and psychological interest. The old mystery of the Lyons Mailthe crime of 27 April 1796alias Floral 8 an IVhad always interested me, and I had often felt desirous of studying its much-disputed detailsthey give a welcome distraction from the shriek of the siren, and take ones mind away for a few hours from domestic and national anxieties.

This story contains, I think, the most interesting criminal problem that has ever attracted my attention. The crime is not even now forgotten, as those remember who, like myself, have seen both the younger and the elder Irving play the double-part of Lesurques-Dubosq in the ever-green melodrama of the Lyons Mail. The play makes havoc with the actual happeningsbut gives wonderful opportunities to the actor who can double the partsto use the modern equivalentof Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

But it is not the play but the complicated evidence of the real crime of 1796 which attracts the historians eye. Nothing can be more interesting than this sideshow of France in the years immediately following the crisis of the Revolution. It gives us a sort of aftermath of social and even of political history, with most unexpected figures turning up incidentally in this long record of crime. The lost money, which was the original cause of the tragedy, was on its way to General Bonapartethen engaged in his first triumphant campaign in the Genoese Apennines. Ten years after, it is the Emperor Napoleon, now the dominating personage in Europe, who casts a cursory eye over the Lyons Mail Affair and sends the papers to be dealt with by his Minister of Justice. Three of the members of the Directorate which presided in a somewhat spasmodic fashion over the destinies of pre-Napoleonic France were successively interested in the caseGohier, Larevellire-Lepeaux and Merlin de Douai, as judge, director, and Minister at critical moments. Gohier is specially prominent as a very blustering occupant of the bench. Talleyrand looks in for a moment as Foreign Minister, to demand the extradition of an assassin. Madame Tallien, Notre Dame de Thermidor, makes a flitting and undignified appearance at one session. Still more unexpectedly Brillat-Savarin, the famous epicure, turns up as Commissaire du Gouvernement at the last of the many trials. Cambacrsanother epicurepresided at the meeting of the Council of Five Hundred which rejected Lesurquess appeal: he was to end as Bonapartes Second Consul and Chancellor.

But it is not the glimpses of historical personages that most interest the readerit is the eternal interplay of the three possibilitiesmotive, opportunity, evidencewhich are presented to him. The evidence is copious and contradictory: the opportunities contestablethe motives of the leading figures in the one case obvious, in the other possible but doubtfully sufficient. But the evidence tells heavily against the man with the smaller inducement. We get led off into studies of psychology, not only of ruffians, but of commonplace country folk, and of lawyers and magistrates. One legal lightDaubanton, the year-long and self-assertive champion of a lost causereminds us of Dr. Kenealy and the wrongs of the Claimant in the Tichborne Case. President Gohier on the bench sometimes recalls the hectoring manners of Judge Jeffreys. But he was only an exceptionally well-developed type of that sort of continental judge who can not keep out of undignified logomachies with an impudent prisoner in the dock. In Jean Guillaume Dubosq we meet the criminal with the greatest sense of humour on record.

The amount of material forthcoming for the study of the Lyons Mail case is enormous. Most of the original manuscript documents survived to the nineteenth century and were reproduced in facsimile. We can study the letters of Lesurques and Dubosq, who, however nearly they may have resembled each other in physique, were also alike in being possessed of a small, neat and legible handwriting. Graphologists, if they will, may try to interpret their characters from their script. There are also slanting and illiterate scraps from some of the known murderers. There are scores of pamphlets and leaflets, produced at intervals extending over many years, from the believers andless numerousthe disbelievers in the innocence of Lesurques. Solid books are also forthcoming, notably one of Salgues, which marshals the evidence in great detail on the exculpatory line. But the monograph of Gaston Delayen (1905) has proved to me most valuable of all, by its copious photographic reproductions, not only of official documents but of the actual script of many of those who were concerned at first-hand in the affair. The official documents enable us to correct innumerable misrepresentations by the pamphleteers and journalists of both camps, many of whom seem to have been perfectly reckless in their assertions. The author of the article on Lesurques in the Biographie Universelle makes the astounding statement that eighty inhabitants of Douai came at their own expense to witness to the honorabilit